Бесплатный фрагмент - Chords. Golden steps of harmony. Part 2

Self-study guide to music theory for all instruments

Machine translation from Russian

Mikheyev Sergei Alekseevich

Chords. Golden steps of harmony

Part 2 of 3

Self-study Guide to Music Theory for all instruments

Start

(The author has the right to all materials in the book.)

Table of Contents for Part 2 of 3

SECTION 1. MUSICAL NOTATION

Chapter 1. Notes, intervals, symbols.

Chapter 2. Abbreviated notations of chords and keys.

Chapter 3. Scales and keys.

SECTION 2. HARMONY

Chapter 1. Chords.

Chapter 2. Table of chord degrees.

Chapter 3. Table of fourths of keys.

Chapter 4. Table of fourths of chords.

Chapter 5. How to determine the key.

Chapter 6. Harmonic moves.

Chapter 7. Transferring harmony to another key.

SECTION 3. RHYTHMICS

Chapter 1. Formation of rhythm.

Chapter 2. Syncopations.

Chapter 3. Reading rhythms.

Chapter 4. Complexity of rhythm and shifting of pulsation.

Chapter 5. Time organization of works.

SECTION 4. MELODICA AND CHORDS

Chapter 1. Basic rules of melody.

Chapter 2. Combination of melody, harmony and rhythm.

Notes: Autumn (song).

Chapter 3. Determining harmony from the text of the melody.

Chapter 4. Complicating melody and harmony.

Chapter 5. Transferring the melody to another key.

Working with the Colored Insert.

COLOR INSERT

1. Universal Quart Table of Chords and Keys.

Three Quart Tables of Chords for G//Em, C//Am, F//Dm.

2. Quart Table of Chords with Notes for Keys C//Am.

Harmony Moves in C//Am.

3. Quart Table of Chords with Notes for Keys F//Dm.

Harmony Moves in Symbols.

4. Quart Table of Chords with Notes for Keys G//Em.

Harmony Moves in G//Em.

This is where part 2 ends.

Of course, the author did not write this book for himself. Not as if for himself. When the author started making music a long time ago, he looked for and saw many books. But the author and his fellow musicians wanted another book, which did not exist then. Simple, understandable and about all music at once. And now the author has tried to create exactly the kind of book that he and his comrades would have liked to see in those distant times.

The book was written to help all beginning musicians. Children, students of regular and music schools. And also ordinary adults, students of any non-musical educational institutions, drivers and carpenters, saleswomen and office workers, soldiers and sailors.

Some of them need the beginning, but what comes next — they do not need. But others already know the beginning, they are not interested in it. — They are interested in what comes next. Let everyone find exactly what they need. The main thing is that everyone finds and understands what they were looking for. And how deeply you will study and apply it, how much time and effort you will devote — this is your business, dear reader.

Nowadays there are such programs on computers that it is not necessary to overstrain your hands. You can program music. But in order to program it, you need to understand — MUSIC THEORY.

Section 1. MUSICAL NOTATION

Chapter 1. Notes, intervals, signs

Notes

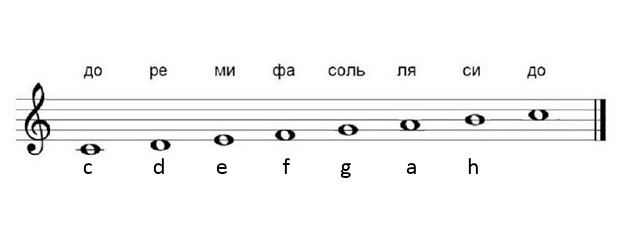

Remember very well the location of the notes “do”. And count up or down from them. If you still have difficulty finding any note on the staff.

The notes should be exactly one “step”: on the first additional line below, under the first large line. On the first, between the first and second, on the second, etc.

Intervals

INTERVAL is the distance between any two notes. The unit of measurement of a musical interval is a tone. A tone is the difference in pitch between two adjacent notes, for example: DO and RE. G and A.

Exception: between the notes MI — FA and SI — DO the interval is equal to a semitone.

Let’s single out “pure” notes, i.e. notes without signs (sharps or flats). On the piano, they are on the white keys. Black keys are used to play notes raised or lowered by a semitone. “D — SHARP” is “D” raised by a semitone, this is the black key to the right on the keyboard, between “D” and “MI”. The note “MI — FLAT” is played with the same key, but is designated differently. Let’s say this: they are practically equal, but theoretically different.

Intervals:

MI — FA = SI — DO = semitone. Do — RE = 1 tone. Do — E = 2 tones and so on.

For now, we only need an idea of three intervals: a semitone, a tone and an octave. An octave is an interval between two closest notes of the same name (the first and the eighth). Examples: Do — Do, RE — RE, RE SHARP — RE SHARP, etc. All octaves, of course, are equal in the number of tones they contain. (Count if you don’t believe me.)

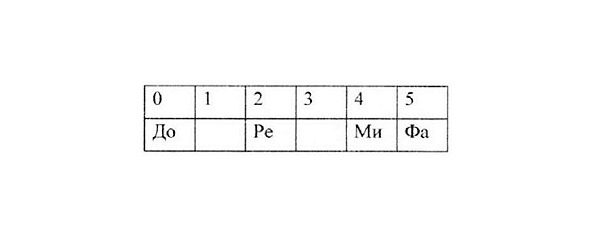

It will be most convenient for us to count intervals by the number of semitones. We will get the same result by counting keys, frets (on a guitar) or cells in tables. Example: interval DO — F = 5 semitones = 5 keys = 5 frets = 5 cells.

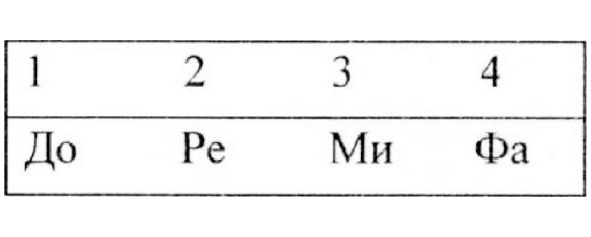

Remember the difference between counting notes and counting semitones.

— In the first case, we seem to answer the question: Which note? And we count like this: FA is the fourth note from C.

— 2.

— In the second case, we answer the question: What is the distance?

And we count like this:

The interval (distance) from F to C is equal to 5 semitones (or 5 cells, keys, frets).

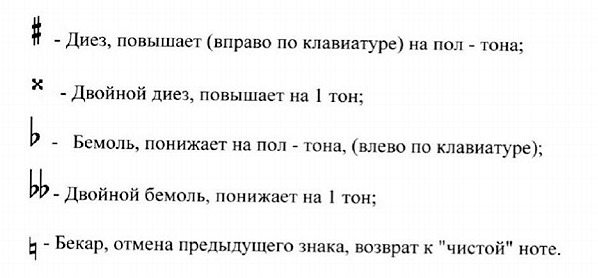

Signs

Sharp — raises by a semitone. Double sharp — raises by a tone. Flat — lowers by a semitone. Double flat — lowers by a tone. Natural — cancels the previous sign.

Don’t be surprised, DO double sharp and RE are practically the same note, but theoretically they are different notes.

There are key and local signs.

Key signs are written at the key at the beginning of each line (unless they are changed to signs of another key in the middle of the line). They affect the entire line — except when they are changed by local signs.

Local signs affect 1) from the place of their occurrence to the end of the measure. 2) Or until the next sign before the same note, if the note is within the same measure.

ORDER OF SIGNS

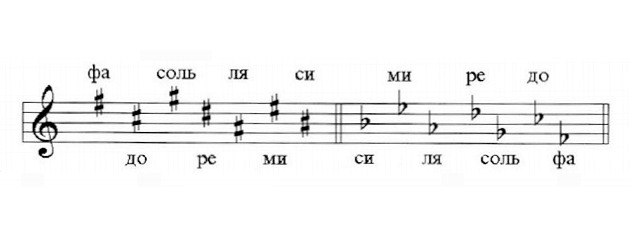

Key signs occur in a strictly defined order. This resembles a chessboard. Sharps occur like this:

Fa sol la si

do re mi

Get the idea? And flats occur the other way around:

Si la sol fa

mi re do

If we are talking about a key with one sharp, then this is, of course, F SHARP. If there are 2 sharps, then it is F SHARP and C SHARP. And so on. Now let’s draw these signs on the staff.

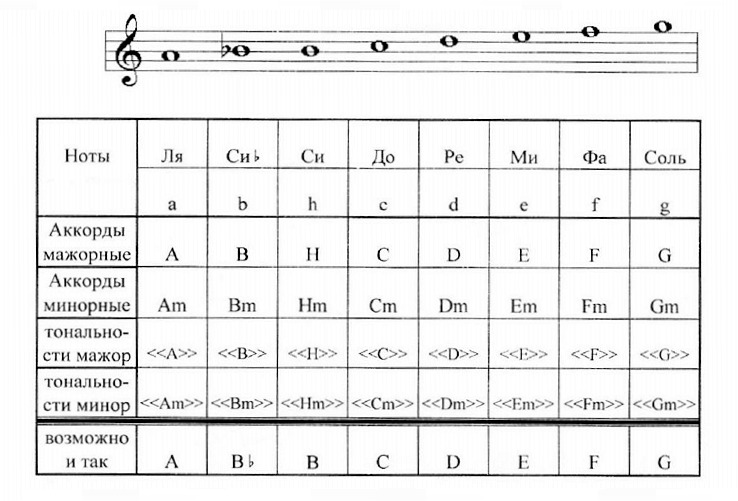

Chapter 2. Abbreviated notations of chords and keys

Table of abbreviations

The last line is a new notational tradition.

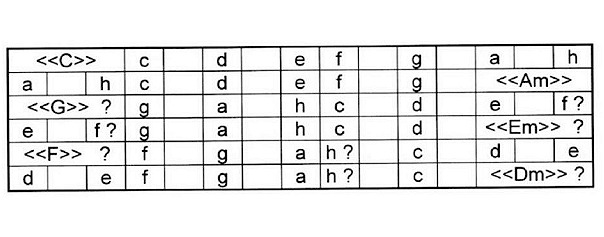

Chapter 3. Scales and keys

Gamma

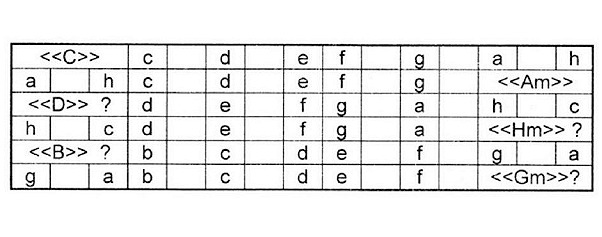

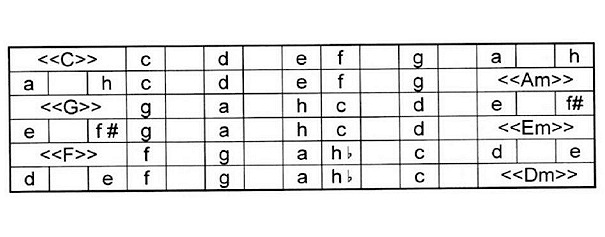

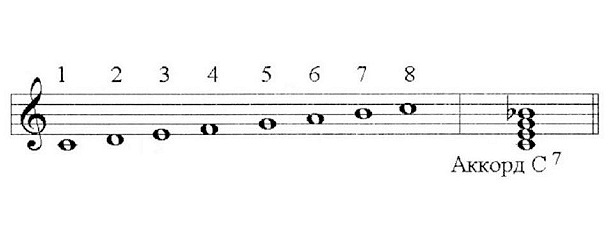

A scale is a series of seven notes, located at strictly defined intervals from each other. There are two types of scales: major and minor. Their name is determined by the note they begin with. Let’s build a table for the scales “C” and “Am”:

Scales that consist only of “pure” notes are called natural. There are two of them: “C” and “Am”. PARALLEL scales are those that use the same notes, but in different orders, with the same key signatures. There are only two such scales from the same notes: major and minor.

A series of natural notes that begin with any other note than c or a is not a scale at all… A scale is a series of notes from which a melody is mainly built. A scale determines the key. The scale “C” determines the key of “C”, the scale “Am” determines the key of “Am” and so on.

Parallel keys are located at a distance of three notes or three semitones from each other. Minor — below, major — above in sound, like this:

La — – Do Mi — – Sol Re — – Fa

When we doubt which note — then we count the third note and there will be no doubt. It happens that scales begin with notes with # or with Ь. Remember all this well. If you learn to easily build scales, then you will easily build chords. But this is further.

Scale is built like this: we take two scales as a model: “C” and “Am”. Then we sign the notes of the natural scale without signs according to the notes of the model. We start with any selected note — minor under minor, major under major. And then, checking the intervals between notes with the natural scale, we correct the notes with signs.

Why”? ”. Because in “D” and “Hm” the interval e — f is broken. And # must be added to Fa. And in “B” and “Gm” instead of h there will be b. Like this:

Note: h Ь = B = Si flat.

First learn to build scales (and then chords) using the tables in the notebook. Then we will get acquainted with a large table of keys, which you can use to look up the answers. And later you can learn all this by heart and build it in your mind or with the help of a musical instrument. For now, you don’t need to memorize everything too hard. The main thing is to understand. And you can look at the tables as much as you like, leafing through the book again and again. Gradually, with some effort, everything you need will be remembered by itself.

This is what a couple more scales will look like:

Both the top and bottom lines (they are called staves) contain the same scales, only the top line uses local signs, and the bottom line uses key signs.

SECTION 2. HARMONY

Simply put, harmony in music is a sequence of chords depending on the melody and rhythm. Or a theory about it in general — or in a specific piece. Moreover, harmony is often simply called a sequence of chords.

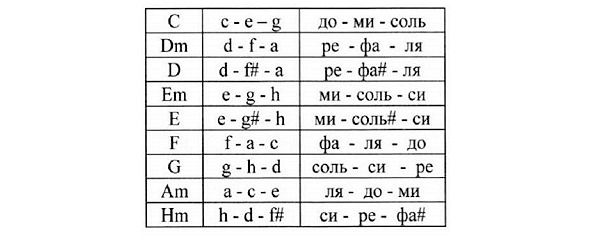

Chapter 1. Chords

You can’t even imagine how quickly and easily you can build chords!

Place your hand on the table, palm down, with your fingers spread wide apart. Imagine that five fingers from left to right are five notes. Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol. Take every other note — 1, 3, 5. Touch the fingers — notes with the finger of your other hand: one, three, five. We get the chord DO — MI — SOL.

In principle, any combination of notes can be called a chord. We need simple chords now. Those that are designated by letters and numbers: C, Am, Em 9, B +7, D dim, E sus, C maj, H 7/-9 — etc.

But let’s get back to your hand. DO — MI — SOL is a DO — MAJOR chord. In this way, you can build any chords, counting only the notes on your fingers according to the natural scale. True, then you need to look at a special table and correct (if necessary) natural notes with the signs “flat” and “sharp”. Double and even triple signs (sharps and flats) are also used, but this happens rarely.

Each chord is built on its own scale of the same name. But the melody sounds in its own key. — With an adjustment for the chord.

You can also do it this way: calculate the chord by intervals. Major: 2 tones plus 1.5 tones. Minor — on the contrary, 1.5 tones plus 2 tones. That is, minor chords differ from major chords only by the 3rd step — it is lower by a cell (by a fret, by a key).

Let’s build some more chords.

What we have just built is also called triads. Of course, there are non-chord triads, but we are not talking about them now. Based on theoretically constructed chord triads, a chord is built for physical performance on an instrument.

The location and number of notes in a chord do not change the chord. But it is desirable that the bass be of the same name as the chord. In addition to the main steps (1 — 3 — 5), the chord may have additional steps. Then numbers or letters are written next to the chord designation.

Unanswered question (to improve the mood):

Can you guess what the chords C#? Cb?

Now let’s build chords on the staff. It’s as easy as on your fingers. Remembering the natural scale, count in your head and write the necessary notes — skipping unnecessary ones. First build a chord, then identify the notes and correct them with signs. Everything that concerns the construction of chords will be explained very clearly below.

If you need to build a difficult chord, say F#7/9, you can build a simpler one, for example: F 7/9, and move all the notes up 1 space. On the guitar, you can take the chord F 7/9 and simply move all your fingers up 1 fret (this will be down the fretboard). Now we build F#7/9 on the staff.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.