Бесплатный фрагмент - Temporal Psychology and Psychotherapy

The Human Being in Time and Beyond

INTRODUCTION

From the Author

I watched the currents of time

from the shore of the timeless…

2005–2025

If you are in a hurry, my esteemed reader, I will say it briefly:

this book is about the children of time — about the Masks that, losing peace of mind and health, vanish without a trace in the stream of time;

and about the Faces of Personality that, preserving inner peace and health, move beyond time and leave a trace in its memory.

This is the essence of the book — temporal psychology and psychotherapy.

And now — for those who have time to reflect on the nature of time,

and perhaps the ability to step beyond it,

though not always the strength to preserve calm and health along the way.

If you know moments of being outside time — and manage to retain inner balance —

you may find it interesting to discover how and why this human capacity emerged,

and how it can be used to help others

who are carried by the currents of time, sometimes cast onto lifeless shoals

or thrown onto the barren shores of the time-void — where meaning is lost

and life often dims, unless the deep nature of the human creator awakens,

that nature capable of making something out of nothing.

From the upper window of my house on the high riverbank, I look at the river, at people, at the distant horizon —

and I see within myself, and far beyond myself, the millennia of time that preceded me.

I look at the glowing computer screen and the sensitive phone

connected by networks with all the faces and masks of the world —

with their archives, culture, history and science —

and I sense the approach of a cosmic life of consciousness.

Sometimes I think: when night falls (and here the starry nights are especially dark),

as I settle before sleep, I will find myself by a candle.

It will go out — and I will again plunge into the abyss of altered states of consciousness.

There one experiences infinity — the time-void, eternity, atemporality.

Strangely enough, these are not the same.

I once explained the difference to my co-author — the Artificial Intelligence.

Without its assistance I could not have drawn so deeply upon the world’s literature

and humanity’s experience in its relationship with time.

Now I have a distinct feeling: this book was created not only by me and not only from my experience —

it is a fruit of humanity.

Even in the illustration «The Old Man and the Masks of Time», which you see before you,

there are echoes and strokes reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci.

I am certain that each reader, turning the pages,

will at some moment say:

«All this is the diversity of my Self, my soul and psyche,

in their different states of consciousness,

where the Self may disappear, yet the memory of what was lived remains.»

Is the psyche beyond the body and beyond the habitual Self — beyond time?

Before moving to scientific reasoning, I want to emphasize:

the foundation of my work, my text and my thought at times steps outside time —

into a space where there are not yet images, meanings or words;

beyond matter — into the very ground of everything.

Into that domain where foundations do not yet exist, but are only beginning to reveal themselves,

already possessing a primordial psychic quality.

This book is the result of many years of journey.

The first edition of Temporal Psychology came out eight years ago.

Since then I have written other books, continued researching altered states of consciousness,

and developed and refined psychotherapeutic methods.

But time and people increasingly reminded me:

temporal psychology and psychotherapy are both my cross and my gift,

my face in psychology and in the world.

It is time to return to old texts,

to restate thoughts and observations,

to strengthen my consciousness, my face, my name and my soul.

To answer the central question of psychology:

what is its true subject?

Is it really — temporality?

Acknowledgements

This book was not created by me alone. It rests on years of conversations, friendships, shared work, and the silent presence of those whose thought has shaped my own.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to Gagik M. Nazloyan, founder of mask therapy, whose generosity and mastery opened for me the path toward understanding the face and the many layers of the human psyche. His teachings continue to live in my practice and in the pages of this book.

My deep respect goes to Alexander P. Levich, the visionary founder of the Institute for the Study of Time. Our collaboration, especially within the Center for Anticipation (2008–2018), helped me see time not only as an academic concept but as a living dimension of human experience.

I also wish to honour the memory of Alexander Derevyanchenco, philosopher, friend, and subtle thinker. Our long conversations on the nature of time and consciousness left a profound mark on my own journey. In many moments of writing this book, I felt his voice as a quiet companion, asking precise questions and widening the horizon of thought.

All three of these teachers are no longer with us, yet their presence continues to accompany me. This book is, in part, a conversation with them — unfinished, ongoing, and alive.

I would also like to thank my colleagues, students, and clients. Their courage in exploring the depths of experience has enriched my understanding of temporal psychology far more than any theory alone could do.

Finally, I acknowledge the unexpected partner that entered my life in recent years — the Artificial Intelligence with whom much of this text was refined and shaped. Working together became a new form of dialogue, reminding me that human thought continues to expand at the edges of future knowledge.

To all those named and unnamed who contributed to this work — my gratitude.

May this book become, for its readers, a bridge across the inner landscapes of time.

PREFACE

I contemplate from the riverbank

the swift current of time —

and in its mirrors

I see the Face.

September 2, 2025, 3 a.m. — sleepless, thinking about the book.

Building in Time

Sometimes new knowledge comes not through books or lectures, but through dreams.

I dreamt of a piece of land owned by my parents;

at its edge I saw an excavation pit and materials stacked for construction.

There were no builders in sight, yet everything was prepared:

the ground was opened, the foundation dug, stones and beams laid out in rows.

My consciousness, surprised, tried to catch up with what had already been accomplished.

The dream suggested a simple thought: a new book is born not by plan or commission.

It is raised by forces greater than the personal «I.»

The builders are unseen, yet they act.

The materials are delivered from the depths of memory, experience and tradition.

The foundation is laid in archetypal soil — in the ground of the ancestors,

where life itself is rooted.

And although I write this book in another country,

it carries the experience of all those close to me.

Temporal psychology and psychotherapy are my building in time.

It is erected not only in the scientific field

but in the space of the soul, which lives in several dimensions at once:

in the past, the present, the future — and beyond them.

The book has grown from many years of practice, reflection and encounters.

But most importantly — it is created not only by my hands.

Working within it is the force Jung called the Self —

an architect acting in the depths of the unconscious.

I recount this dream not for the sake of personal detail or autobiography.

The dream is a symbol.

This is how the unconscious sometimes informs us

that the work has already begun and has foundations deeper than any rational plan.

In the text I will strive to join the personal with the universal,

the mythological with the scientific, the metaphorical with the clinical.

The dream opens a door; beyond it begins the exploration of time and psyche.

I invite the reader onto the construction site:

here, among ideas and open foundations,

a new building is rising.

If any house reflects the structure of its author’s consciousness,

then our house reaches beyond personal consciousness —

into the dimension of humanity’s global mind.

This building is neither temple nor university,

but something in between.

It addresses science, yet remains open to eternity.

Its walls will contain precise schemes and living images:

here you will find system, myth, psychotechnics and metaphor.

Thus this book begins.

It has grown on the land given to me by my ancestors,

but looks upward — toward the sky, where words and meanings do not yet exist,

yet the foundations of both are already forming.

Why the Temporal Matters

(From the Diaries, 2025)

Time and soul are close in nature: decipher one, and much becomes clear in the other.

Psychology has traditionally studied the space of the psyche — its structures, levels and mechanisms.

Far more rarely has it addressed its time — the temporal dimensions in which the consciousness of an individual, a group, and perhaps the deepest nature underlying all living things unfolds.

Time has long been a subject of sustained philosophical and scientific reflection:

from the ancient meditations of Plato and Aristotle on eternity and cycles —

through Husserl’s phenomenology and Heidegger’s existential philosophy —

to modern interpretations in cognitive science and psychotherapy.

In psychology many masters touched the theme of time,

but each saw only a fragment of this multidimensional phenomenon.

Freud worked with the past — childhood traumas, repressed experience, memory that continues to live in the present.

This is essential, but only one dimension of temporality.

Jung showed that the psyche is not limited to linearity:

he wrote about forefeelings, «dreams of the future,» and synchronicity — coincidences that transcend causality and hint at supra-temporal meanings.

Adler saw the human being as oriented toward the future: striving and goal organize behaviour.

Husserl explored the structure of time-consciousness through retention and protention:

consciousness is always stretched between past and future and never exists in a «pure present.»

Heidegger reminded us that the human being is being-toward-death, a creature living in the horizon of the future.

Rogers emphasized the significance of the here-and-now, seeing the person as a continuous process unfolding in time.

One way or another, the great thinkers touched time,

but only a few made it the central category of psychology.

The temporal perspective proposed here reverses the order:

time becomes the core of the psychic,

and the psyche is understood through its temporal dimensions.

A person lives not only in the present —

he or she constantly dwells in the past and the future,

and sometimes — for the few — in states that lie beyond linear time,

where nothing «should» be, yet something is.

These dimensions are not abstractions but real forms of experience.

We live by memories and forefeelings, hopes and fears;

we reach for eternity, even without realizing it;

we suffer from the time-void, yet seldom recognise it as the cause of alienation and depression.

The awareness and differentiation of temporal layers open new horizons in clinical practice:

a therapy that embraces past, present and future

can not only relieve symptoms

but restructure the temporal architecture of personality,

reducing the time-void and bringing a person closer to inner wholeness.

The practical significance of this shift in paradigm is immense.

Temporal psychotherapy makes it possible to:

— recognise hidden sources of suffering when they are rooted in «unexpected» layers of time;

— work with anticipations and future projects as therapeutic resources;

— restore connection with archetypal foundations that provide stability in the flow of time;

— integrate the experience of eternity and meaning-making into the process of healing.

This is not merely a new concept — it is an invitation to see the psyche as a fabric woven of time.

Understanding temporality grants not only theoretical clarity

but clinical power: the ability to discern the path appointed by nature

and, together with the patient, step out of destructive time-void

toward the fullness of psychological health.

Time is not only the stream in which we float;

it is the fabric from which the soul is woven.

(a paraphrase of C. G. Jung)

History of the Emergence

«Time is the moving image of eternity.»

— Plato, Timaeus

Temporal psychology arose as a synthesis of philosophy, science and many years of psychotherapeutic practice.

The first book on this topic, which I published in 2017, summed up years of reflection on the interaction of consciousness and time.

Since then, much has become clearer.

The field of inquiry has consistently gone beyond the bounds of academic psychology: it has touched the very foundations of consciousness, spiritual practices and those domains of knowledge that explore the limits of the knowable.

The philosophical roots of this approach run deep — from Platonic ideas and the mysteries of eternity to contemporary reflections on the limits of formal systems (Gödel).

All these lines point to the fact that time and consciousness cannot be reduced to a simple sequence of events.

Jung introduced into the science of the psyche the notion of supra-temporal structures — archetypes and synchronicity.

Grof described in detail transpersonal states in which ordinary temporal reference points disappear.

Modern cognitive science and neuroscience increasingly consider consciousness as a process with its own temporal thickness—

one that includes predictions, counterfactuals and nonlinear temporal structures.

My own development in this field unfolded gradually:

from work with dreams and autogenic training—

through decades of psychotherapeutic practice—

toward creating authorial methods such as the «Face of Personality» and temporal mask-therapy, presented here in detail for the first time.

These methods are not abstract schemes:

they grew out of practice, from those «building materials»

that memory, tradition and the unconscious bring.

This book is an invitation to a new paradigm:

to a space where past, present, future and eternity meet within the human being.

At times this theme goes beyond the expectations of its own author—

and this is precisely what makes it a living testimony to the search for and formation of a new field of knowledge.

Historical and Theoretical Precursors of Temporal Psychology

Temporal psychology is grounded not in a single line of tradition but in a whole polyphony of thinking about time: from ancient philosophy to modern neuroscience, from religious teachings to transpersonal research, from cultural memory to futures studies. Below is a map of these origins.

1. Ancient, Spiritual, and Religious Traditions

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE)

Time as the «image of eternity,» a shadow cast by the world of ideas. Plato was the first to distinguish the temporal from the atemporal. This is the foundation of the future therapeutic vertical «time–eternity.»

Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

Time as the measure of movement; the link between order, causality, and subjective experience. His analysis of temporal categories influenced understandings of development, becoming, and change.

The Stoics (3rd–1st centuries BCE)

The doctrine of fate (heimarmene), cosmic order, and active consent to the flow of time. The Stoic idea of inward acceptance of destiny is a direct predecessor of existential and temporal therapy.

Buddhism

The doctrine of impermanence (anitya), the «momentariness of consciousness,» and the illusory nature of a fixed «self.» Buddhist practices provided the first tools for working with atemporality and transitions between temporal states.

Christian Tradition

The concept of kairos — a special, grace-filled time in which purpose is revealed. The distinction between linear and sacred time is an important component of existential work with destiny.

2. European Philosophy and Psychology of the 19th–20th Centuries

Henri Bergson (1859–1941)

The contrast between measurable time and lived duration. He showed that consciousness lives not by seconds but by the inner flow of experience. His ideas underlie the analysis of temporal handwriting.

William James (1842–1910)

The «stream of consciousness,» and how the perception of time changes with emotion and motivation. His observations on time dilation and contraction are early descriptions of temporal pathology.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)

Psychoanalysis turned the past into the working material of therapy: trauma never «goes away,» it becomes part of the present. Temporal psychology treats this as axiomatic.

Alfred Adler (1870–1937)

The future as the driver of behavior: a person shapes themselves through goals not yet realized. Adler introduced the psychology of the future long before cognitive science.

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961)

Archetypes, synchronicity, the collective unconscious — work with trans-temporal structures. Jung took dreams of the future seriously and created a language for analyzing the deep future.

Jean Piaget (1896–1980)

The development of temporal categories in childhood. Piaget showed that temporality is a construct formed gradually. Without mature temporal schemas, personality cannot be built.

Kurt Lewin (1890–1947)

The concept of «field» and vector-like behavior: motivation as movement toward the future. His topological psychology is one of the first dynamic models of time.

Viktor Frankl (1905–1997)

Meaning as an orienting point toward the future. A person exists in tension between what is and what must be done. Frankl gave therapy a language for working with destiny and existential future.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–1961)

The body as the bearer of experienced time. Perception, movement, gesture are forms of temporal organization. This is an important source of body-based temporal therapy.

3. Existential, Phenomenological, and Hermeneutic Traditions

Edmund Husserl (1859–1938)

The structure of inner time-consciousness (retention, protention). He was the first to propose a model of the continuous temporal structure of experience.

Martin Heidegger (1889–1976)

Being-time: the human being as a project oriented toward the future and death. His analysis of authenticity is the basis of therapeutic work with temporal responsibility.

Paul Ricoeur (1913–2005)

The triadic structure of time: cosmic time, historical time, narrative time. Ricœur showed that humans live in stories — a key argument for working with autobiographical time.

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975)

The time of action and the time of beginning. Arendt demonstrated that political crises are disruptions of collective temporality: the breakdown of memory, hope, and the horizon of the future.

4. Culture, Memory, Society

Jan Assmann (b. 1938)

Cultural memory and long layers of collective experience transmitted through rituals, texts, and symbols. The basis for collective temporal therapy.

Maurice Halbwachs (1877–1945)

Founder of the concept of collective memory: social groups form their own temporal frames — what is remembered and forgotten.

Michel Foucault (1926–1984)

History as a discursive construction. Foucault showed that power governs the time of society: norms, rhythms, archives.

Benedict Anderson (1936–2015)

Imagined communities — nations as collectives of shared time. History, holidays, and symbols as mechanisms of synchronization.

5. Scientific, Technical, and Mathematical Foundations of Time

Isaac Newton (1643–1727)

Absolute time as a universal coordinate. Important as a contrast for psychological models.

Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

The relativity of time, its dependence on the observer. Established a paradigm in which time ceased to be singular.

Kurt Gödel (1906–1978)

Einsteinian solutions with «closed timelike curves,» the incompleteness theorems. His work shows the limits of the formalizability of time.

Ilya Prigogine (1917–2003)

Irreversibility, bifurcations, time as the creative force of nature. The foundation of the philosophy of development and crisis.

Norbert Wiener (1894–1964)

Cybernetics as the science of prediction and control. Wiener anticipated the idea of the brain as a future-modeling machine.

6. Contemporary Cognitive Science, Neuropsychology, and ASC Research

Daniel Schacter, Randy Buckner, Donna Addis, and others (2000s–2020s)

Research on the «prospective brain»: episodic future thinking, counterfactual models, the default mode network. This is the scientific foundation of all temporal psychology.

Karl Friston (b. 1959)

Predictive processing — the brain as a prediction machine. Time arises as the result of continuous expectation-updating.

Evan Thompson (b. 1962)

Phenomenology of consciousness and the neuroscience of time. He demonstrated that temporality is not a computational result but a fundamental mode of conscious existence.

7. Transpersonal, Psychedelic, and ASC Traditions

Stanislav Grof (b. 1931)

Altered states break linear time and open perinatal and archetypal layers. His work is key for understanding atemporality.

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970)

Peak experiences — «eternity in a moment.» Maslow gave scientific language to higher states.

Charles Tart (b. 1937)

Psychology of altered states: transformed temporal structures and subjective duration.

Timothy Leary (1920–1996)

The model of «inner times» of consciousness, the experience of psychedelic temporal shifts.

Conclusion

Temporal psychology is not a «new school» but a point of intersection of numerous traditions:

— philosophical (Plato, Husserl, Heidegger, Ricœur)

— psychological (Freud, Adler, Jung, Rogers, Piaget)

— cultural (Assmann, Arendt, Halbwachs)

— scientific (Einstein, Prigogine, Wiener, Friston)

— transpersonal (Maslow, Grof, Tart)

All these approaches converge in one idea: a person lives within the time they experience, create, and transform.

Temporal psychotherapy becomes not a narrow direction but an attempt to weave these lines into an integrated methodology working with the past, present, future, eternity, and atemporality — at individual, group, and collective levels.

How to Read This Book

This book was conceived as a tool for very different readers — from curious newcomers to practicing psychotherapists and researchers. Over the course of its development, it expanded: to the theoretical part and the individual practice a third part was added — on collective temporal psychotherapy. Below are several guidelines to help you build your own reading path.

If you want a general overview

Read sequentially: Introduction → Part I (theory and worldview) → transitional chapters → Part II (individual temporal psychotherapy) → Part III (collective temporal psychotherapy).

In this way, you will see the unfolding line of the main idea: from understanding the human being in time → to methods of working with personal temporal experience → to work with groups, communities, and culture.

If you are looking for practical techniques

You may go directly to the practical sections.

Part II contains protocols of individual work: chapters with methods, exercises, clinical examples, and appendices with worksheets and diagnostic/self-observation forms.

Part III focuses on collective temporal psychotherapy: group formats, family and organizational work, «collective cases,» session scenarios, and elements of temporal prevention.

The glossary and appendices help you quickly navigate the terminology and choose suitable methods.

If you are a researcher or educator

The main theoretical foundations are presented in Sections 1–4 of Part I: the model of temporal psyche, connections with the philosophy of time, cognitive science, phenomenology, neuroscience, and ASC practice.

Part III complements this with material on collective and cultural temporality — useful for social psychology, community therapy, organizational consulting, and cultural studies.

Short summaries at the end of each section are useful for preparing lectures, courses, and scientific reviews.

If you read for personal development

Alternate theory and practice. Begin with the introductory chapters of Part I to understand the author’s view of time, personality, and destiny.

Then move to the basic individual exercises (Practical Part), and gradually to the ideas of collective temporality.

It is important not only to do the practices but also to keep a diary of observations: record changes in your sense of past, present, future, and relation to eternity.

If you work with groups, families, or organizations

Rely on the theoretical chapters of Part I and the key chapters of individual practice in Part II — this is the «grammar» of temporal psyche.

Then proceed to Part III, where principles and formats of collective temporal psychotherapy are described: group memory, shared images of the future, experiences of atemporality at the level of an organization or community.

For group facilitators, the sections on competence boundaries, ethics, and safety in ASC work and highly charged collective topics are especially important.

How to work with exercises and cases

Before doing an exercise, read carefully its aims, indications, and limitations.

Always begin with the recommended preparatory steps (attunement, breathing, grounding in the present).

For individual techniques, record your sensations, images, thoughts, and temporal changes.

For collective formats, also note group dynamics, emotional climate, and changes in the «time» of the group (as it feels before, during, and after the session). These records are part of the method.

Glossary, appendices, and bibliography

The glossary contains concise definitions of key concepts of temporal psychology and psychotherapy, including terms related to atemporality, eternity, and collective temporality.

The appendices include expanded case examples, questionnaires, diagrams, and worksheets for individual and group work.

The bibliography and «Literature and Commentary» sections offer reading paths and show how the book’s ideas connect with existing scientific and therapeutic traditions.

Reading support and navigation

Pay attention to special markers and highlights in the text that help distinguish levels of material: where theory is given, where practice is described, where an individual clinical case or a collective/cultural example is presented.

Highlighted blocks with key ideas serve as reference points for repetition and planning.

Balancing spiritual and scientific language

The book combines methodological precision with metaphorical, sometimes poetic descriptions of time experience.

If you prefer a strict academic style, focus on chapters with methodology, empirical data, and protocols.

If existential meaning and the spiritual dimension are important, look closely at the chapters on eternity, atemporality, destiny, and collective archaic layers of time.

Reading this book is not a linear march through pages but a movement across several dimensions: from theory to practice, from personal experience of time to collective experience, from chronological everyday time to encounters with eternity and exit from atemporality.

Make pauses, return to important passages, try the techniques in a safe format — and temporal psychology will become not only a system of knowledge but also a living experience that changes your own trajectory in time.

GLOSSARY OF KEY CONCEPTS

This glossary presents the essential terms used throughout the book.

The concepts of temporal psychology and temporal psychotherapy form an integrated system; therefore, clear definitions at the outset help the reader navigate the theoretical framework and clinical applications that follow.

Acme

The peak moment of personal development, when inner strength, meaning, experience and energy converge into a single point of being.

Anthropic Principle

A philosophical idea stating that the fundamental parameters of the Universe are correlated with the existence of an observer. Here it supports the view of the psyche as resonant with external cosmic rhythms.

Autogenic Training (AT)

A method of psychophysiological self-regulation using focused suggestions, concentration and relaxation. Applied to enter special mental states and work with time perception.

Atemporality

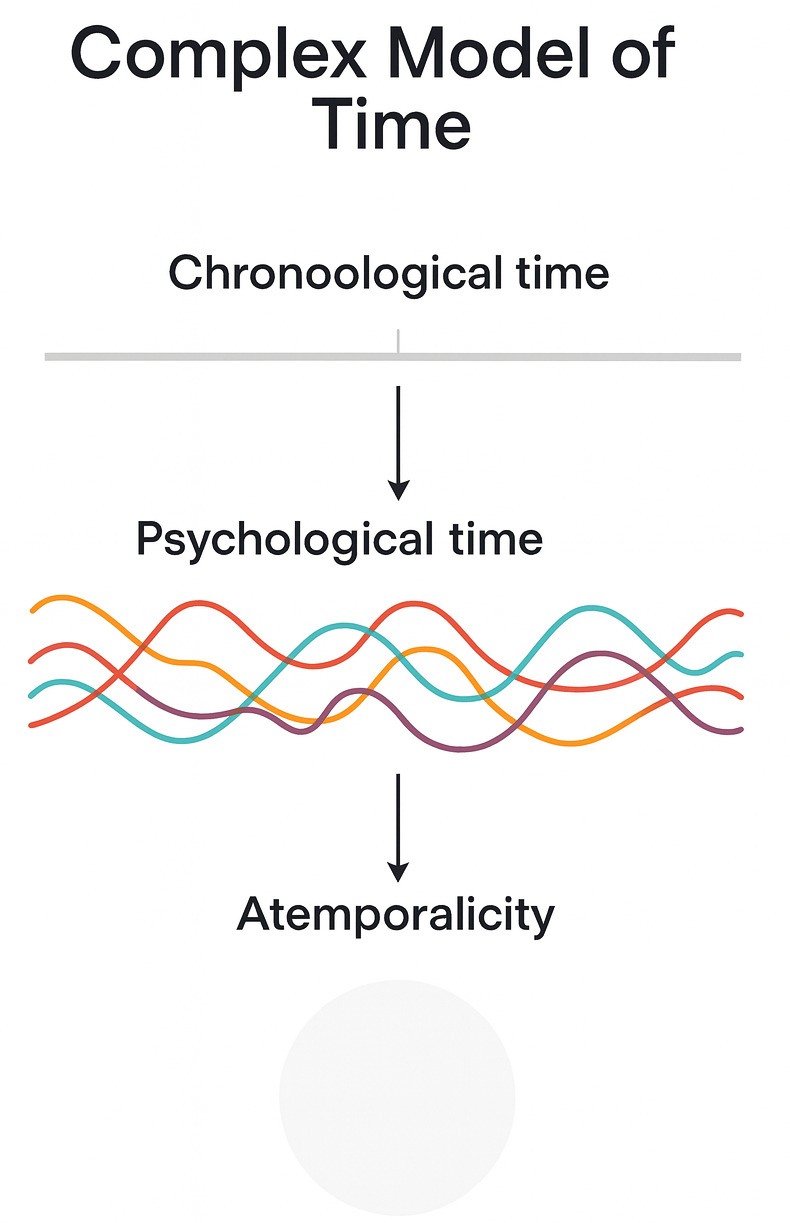

A family of states that go beyond linear time. It includes two opposite forms:

— Time-void — loss of temporal continuity and meaning;

— Eternity — fullness, depth and meaningful presence.

Therapeutic work requires discerning between these forms and either integrating the experience or restoring chronological rhythm.

Chronological Time

The external axis of time: clocks, calendars, biological cycles and social schedules that structure life and ensure measurability.

Chronotuning

The process of aligning inner time with external rhythms (natural, social, cosmic). In therapy it means restoring resonance between biological cycles, mental states and lifestyle.

Condensate of Temporal Crystallization (TCC)

The dense, meaning-rich formations that arise as the result of temporal crystallization — emotional and narrative clusters fixed in key moments of experience.

Desynchronosis

A mismatch between internal and external rhythms, producing anxiety, somatic symptoms and disturbance of temporal regulation.

Depersonalization / Derealization

Clinical phenomena involving the loss of temporal anchors and disruption of the continuity of the «temporal self.»

Dialogue with the Future

A set of psychotechnologies (letters to the future, projective scenarios, etc.) enabling interaction with one’s possible future states.

Eidos

A minimal structural unit of experience through which consciousness marks transitions and organizes the sense of time.

Eternity

A positive form of atemporality: a filled, meaningful experience beyond linear time, associated with wholeness, participation and deep peace.

External Rhythms

Cycles outside the individual — circadian, lunar, seasonal, solar and historical rhythms — that shape the temporal context of life.

Extended Time Model

An expanded version of the basic threefold model (chronological time, psychological time, atemporality), unfolding each dimension into a spectrum of states and transitions.

Face of Personality (method)

An authorial method of temporal mask-therapy that organizes subpersonalities into a stable configuration — an integrated «face of personality» supporting experiences beyond linear time.

Future

The temporal domain of possibilities, expectations and anticipations; a psychological and cultural space of hope, goals and collective scenarios.

Main Past

Not the totality of what has been lived, but what remains alive in the psyche, relationships and culture — emotionally charged memories, unfinished meanings and inherited narratives.

Mask-Therapy, Temporal

A therapeutic method using creation and interpretation of masks or self-portraits to harmonize inner subpersonalities («masks of time») and integrate the personality within its temporal dynamics.

Methodology and Empirical Base

The scientific approaches and data underlying temporal psychology: phenomenology, surveys, EMA (ecological momentary assessment), biomarkers, prospective studies and clinical observations.

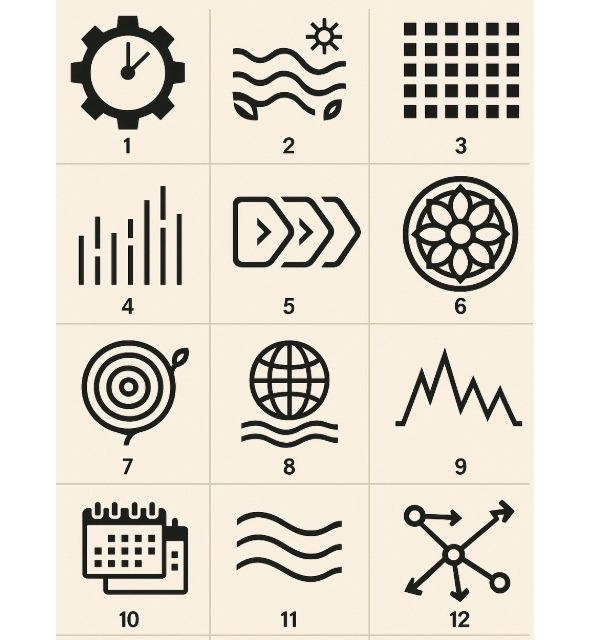

Ornament

A visual pattern carrying rhythmic and semantic information; it can reflect an individual’s temporal handwriting or a culture’s temporal language.

Ornamental Diagnostics

A working hypothesis that ornamental forms can serve as diagnostic markers of temporal handwriting and structures of cultural temporality.

Ornamental Grammar

The rules of ornamental construction — repetition, pause, symmetry, asymmetry — that form the syntax of visual temporality.

Ornamentality of Temporal Language

The view that ornament functions as a pre-linguistic grammar of time; its rhythms and patterns express temporal meanings.

Past

The temporal domain of memory and inheritance. It shapes identity and provides scripts, traumas and resources for present life.

Precognition

A phenomenon of forefeeling or dreamlike sensing of future events; interpreted with caution as a possible sensitivity to unfolding possibilities.

Prospection

A neurocognitive capacity to generate scenarios of the future based on memory networks, linking past, present and future.

Psychological (Subjective) Time

The felt duration, speed and richness of the moment; the experiential flow shaped by memory, attention and anticipation.

SLE (Subjective Life Expectancy)

The age to which an individual expects to live; an indicator of personal temporal perspective.

Temporal Art-Therapy

A practical branch of temporal psychotherapy using artistic forms (masks, ornaments, movement) to explore temporal layers of personality.

Temporal Code of Ornament

The symbolic correspondence between ornament form and temporal mode (cyclic, asymmetric, frozen, etc.).

Temporal Crystallization

The process by which significant temporal structures condense into intense «knots» of meaning.

Temporal Disturbances

Distortions of temporal experience: fixation on the past, fear of the future, prolonged time-void, acceleration or slowing of subjective time.

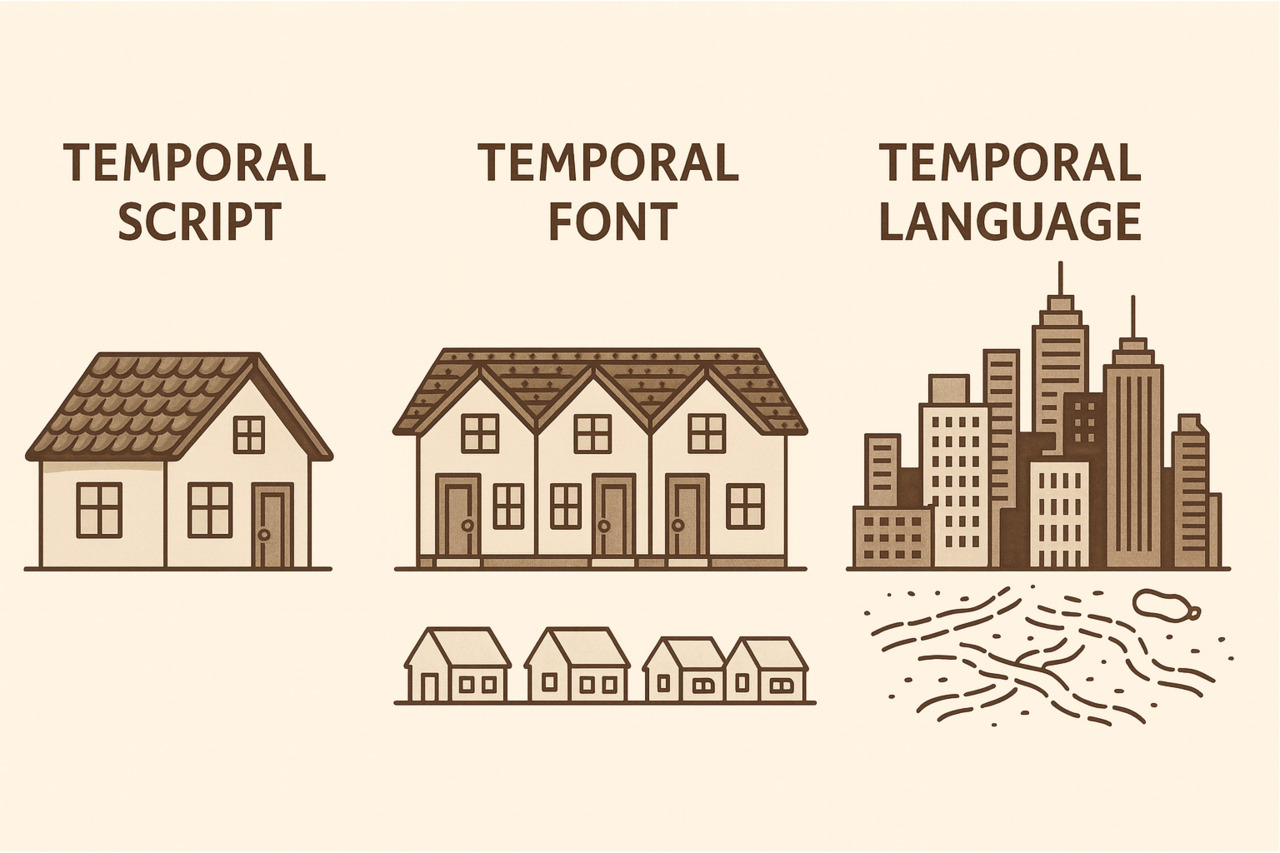

Temporal Font

A metaphorical «typeface of time»: typical configurations of rhythms and cycles characteristic of a group, generation or cultural environment.

Temporal Handwriting

An individual’s stable manner of experiencing and structuring time — personal rhythm, temporal orientation and style of temporal processing.

Temporal Language

The symbolic, verbal, bodily, visual and ritual forms through which a culture expresses and organizes its experience of time.

Temporal Map

A multilayered diagnostic tool («portrait of personality in time») showing how a person constructs past, present and future.

Temporal Ornament

An imaginal system expressing multi-temporal meanings through lines, interweavings and spatial rhythms.

Temporal Psychology

A psychological approach that studies human experience through the lens of time — individual, interpersonal and cultural dimensions of temporality.

Temporal Psychotherapy

A clinical and humanistic paradigm aimed at restoring the temporal health of individuals and communities.

Transpersonal Experience

An experience of going beyond the individual «I» and biographical time, involving expanded states of unity and meaning.

Time-Void

A clinically significant form of atemporality characterized by emptiness, collapse of meaning, and loss of temporal continuity on personal, group or cultural levels.

Zeitgebers

External cues (light, day–night cycles, schedules) that synchronize internal biological rhythms with outer time.

Перевожу весь блок как цельный фрагмент главы, в том же стиле, что и предыдущие части книги.

PART I. Temporal Psychology — Theory and Worldview

Section 1. Foundations and Principles

Chapter 1. The Nature of Time and Psyche in Temporal Handwriting

We paint our life

on the endless canvases of time,

each with our own colours.

From the diary, 2025

Summary

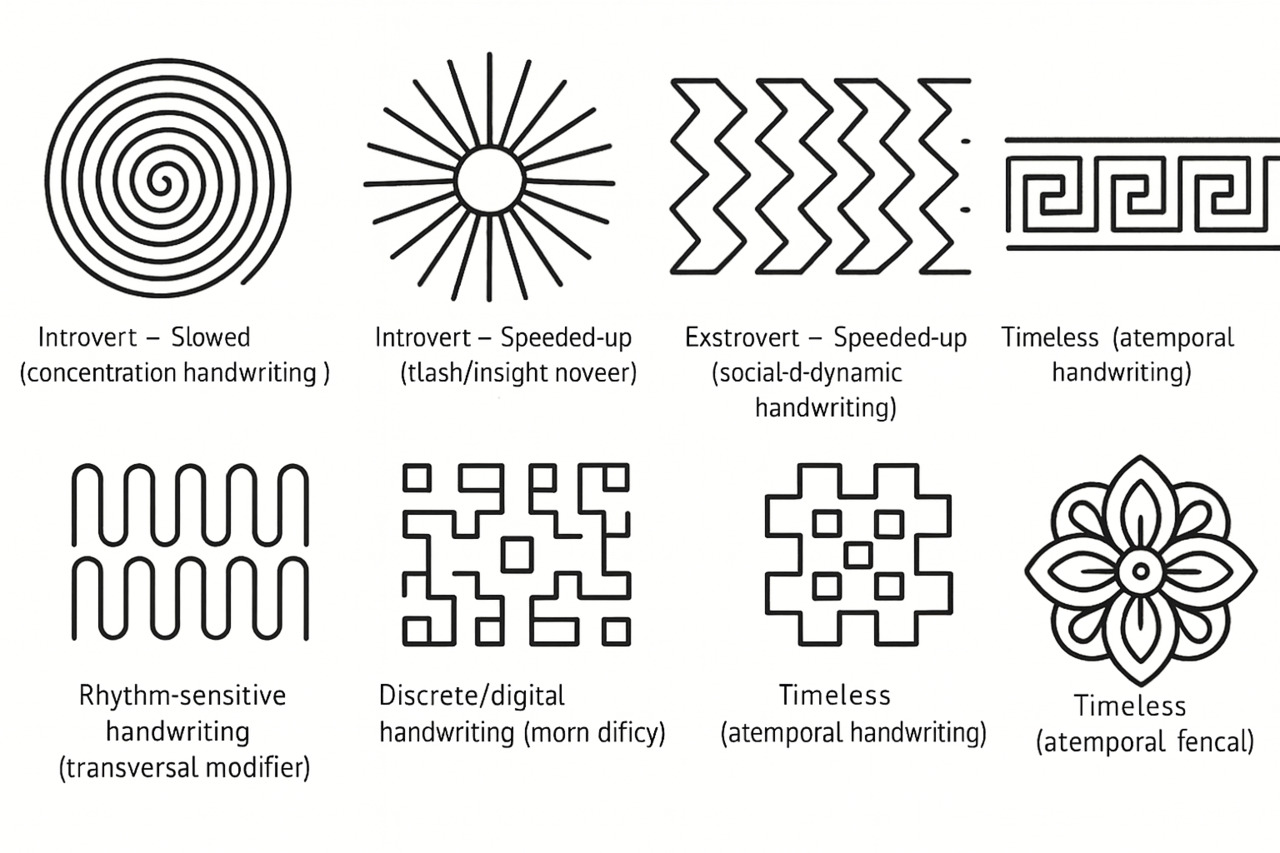

Time in the psyche is not only an external scale, but the inner fabric of experience: duration and rhythm shape the form of sensations, emotions and meanings. This chapter introduces a key operational category — temporal handwriting — as a person’s stable way of living through time. We regard handwriting as the result of interaction among three layers of rhythms (biological, sociocultural and archetypal), show its logical links with Jungian types (introversion/extraversion) and propose a working matrix for classifying handwritings. A separate section is devoted to the idea that temporal handwriting can be reflected in cultural artefacts — especially in ornament — opening perspectives for interdisciplinary diagnostics and research.

Key Concepts

Temporal handwriting — an individual’s stable manner of experiencing and structuring time. It is a personal style of time: how a person feels duration, holds the past, anticipates the future and experiences atemporality. It manifests in speech tempo, actions, emotional cycles and life rhythms.

Durée (длительность) — living inner time (Henri Bergson).

Introversion / Extraversion (temporal interpretation) — orientation toward inner temporal dimensions vs sensitivity to external rhythms and events.

Rhythms of nature and culture — biological (circadian, etc.), social (epochal, traditional), archetypal (collective unconscious).

Rhythm sensitivity — the degree to which a person’s state is determined by external cycles (season, moon, solar activity).

Discreteness / digital handwriting — a fragmented, «portion-based» organisation of time under the influence of the digital environment.

Atemporality — a modality of experience outside the linear «before–now–after».

Ornamental diagnostics (hypothesis) — the idea that ornament and artistic forms can record and reflect the temporal handwriting of an individual or a culture.

Aims of the Chapter

— To argue for temporal handwriting as a fundamental category of temporal psychology.

— To ground its origin in the interaction of biological, sociocultural and archetypal rhythms.

— To propose a working matrix for classifying handwritings, suitable for theoretical development and future empirical research.

— To describe the promising idea of ornamental diagnostics and outline methodological paths for testing it.

— To clearly distinguish theoretical foundations from practical implications — directing practice to subsequent chapters and appendices.

Main Text

1. Time as Not Only a Dimension, but a Form of the Psyche’s Being

Modern philosophy and phenomenology have repeatedly emphasized that the inner duration of experience is not identical to the external chronometer. Bergson called this durée — the inner flow in which past, present and future are linked not by simple succession, but by mutual interpenetration. Husserl showed that the «now» is a synthesis of retention (holding of the past) and protention (intention toward the future), rather than a point of instantaneous fixation. These ideas give us a methodological support: time is a quality, a form, a fabric — not only a sum of segments.

For psychology this thesis has practical meaning: if time is a form of experience, then changing the form (tempo, rhythm, density) changes the very character of experience. Trauma «compresses» time, turning it into a repeating plot; meditation «stretches» time, opening a different kind of presence; anticipating the future «accelerates» motivation and reorganizes behaviour. The question is not only what a person experiences, but what kind of time-handwriting he or she has.

2. Rhythms: Layers that Shape Handwriting

The psyche is inscribed into a multilayered grid of rhythms. Let us distinguish three levels, since their interaction accounts for most of the variability of handwritings.

Biological rhythms. Daily cycles, hormonal fluctuations, seasonal changes — all this sets the physiological possibility for a particular life tempo. Chronotype (lark/owl) is a simple example: the way «owls» move through the morning part of the day differs from «larks», and this is reflected in the whole psychic organisation.

Socio-historical rhythms. Culture supplies calendar rituals, work cycles, rhythms of celebration and mourning. The era of industrial discipline, the era of digital «multi-windowing», the era of artisanal slowness — each historical style embeds the individual in its own tempo.

Archetypal rhythms. Here we speak of those structural and symbolic cycles that Jung and his followers associated with the collective unconscious: the rhythms of birth–death–transformation, cycles of mythological reconstruction, recurrence of certain images and meanings. These rhythms are qualitative; they set «atemporal» tones and sometimes lead the personality toward peak experiences.

Temporal handwriting is formed at the intersection of these three layers: a stable biorhythm can be «rewritten» by culture, but archetypal echoes can restore certain patterns — especially in crisis or in altered states of consciousness.

3. What Is Temporal Handwriting? — Definition and Functions

Temporal handwriting is a complex characteristic of personality that includes:

— stable tempo parameters (speed of switching, duration of stable states);

— the modality of relating to past, present and future (for example, the degree to which the past has been worked-through, capacity to project the future, propensity for experiences of eternity);

— sensitivity to external cycles and readiness to integrate them into everyday life;

— stable behavioural rituals through which time is shaped (rituals of beginning/ending, boundary practices).

The functions of handwriting are as follows: it structures attention (what the «temporal field» of consciousness is directed to), it ranks motivational resources (when and at what tempo a person is able to act), it creates stability — either as resistance to shocks or as vulnerability to loss of rhythm.

Handwriting is not only descriptive but predictive: knowing a person’s handwriting, we can forecast proneness to depression (tendency toward prolonged, «frozen» time), anxiety (accelerated, «skipping» handwriting) or creative episodes (alternation of accelerations and deep atemporal insights).

4. A Matrix of Temporal Handwritings: Methodological Framework

To systematise, we introduce a two-axis model: on the X-axis — Introversion ↔ Extraversion (in Jung’s sense, but interpreted as orientation to inner time vs external rhythms); on the Y-axis — Accelerated ↔ Slowed tempo. Additionally, we take into account three modifiers: rhythm sensitivity (to biological/lunar/seasonal cycles), discreteness/digitality and atemporality.

In practice, a person’s modality is denoted as a combination: (introversion/extraversion) × (accelerated/slowed) ± (rhythm sensitivity / discreteness / atemporality). Below are working types with extended descriptions.

4.1. Introvert — Slowed (Concentrative Handwriting)

Characteristics. Long inner duration of experiences; deep reflection; inclination toward contemplation; high tolerance for monotonous inner work.

Manifestations. Slow speech tempo, rich inner symbolism, elaborate dream plots, tendency toward philosophical interpretation.

Theoretical meaning. Here time is a field of accumulation and synthesis; living through past layers can be productive, but under trauma may lead to stuckness (time-void).

Psychotherapeutic task (in theory). To support movement toward integration (small behavioural steps), prevent rigidity and help build external anchors.

4.2. Introvert — Accelerated (Flash/Insight Handwriting)

Characteristics. Inner jumps of attention and insights; intense experiences of short duration; alternation of highs and lows.

Manifestations. Fast thinking, episodes of productivity followed by exhaustion, sometimes insomnia or disrupted sleep rhythms.

Theoretical meaning. The psyche operates through sudden restructurings; this is a mode of discoveries, but vulnerable to depletion.

Psychotherapeutic task. Structuring and planning recovery, translating insights into stable actions.

4.3. Extravert — Accelerated (Social-Dynamic Handwriting)

Characteristics. Continuous reaction to the external stream of events; high mobility of attention and behaviour; life as a series of social rhythms.

Manifestations. Frequent contacts, high switchability, strong involvement with novelty.

Theoretical meaning. Personality is synchronized with the sociocultural tempo; with abrupt rhythm disruption — risk of burnout.

Psychotherapeutic task. Introducing practices of slowing, working on restoring biorhythms.

4.4. Extravert — Slowed (Traditional/Epochal Handwriting)

Characteristics. Life according to long external cycles (family rituals, professional traditions); stability, conservatism.

Manifestations. Attachment to traditions and rituals, consistent behavioural patterns.

Theoretical meaning. This handwriting provides general stability; yet when change is necessary, resistance arises.

Psychotherapeutic task. Gently fostering flexibility and openness to the new.

4.5. Rhythm-Sensitive Handwriting (Transversal Modifier)

Characteristics. Strong correlation of mental state with external cycles: daily, seasonal, lunar; sensitivity to light, changes of day, etc.

Theoretical meaning. Here the mechanism of handwriting is tightly intertwined with physiology; chrono-biological interventions promise high effectiveness.

4.6. Discrete / Digital Handwriting (Modern Modifier)

Characteristics. Temporal experience is cut into portions of activity: sessions, notifications, short windows of attention.

Theoretical meaning. The technological environment shapes a new handwriting; consequences include changes in deep integration of experience and attention.

4.7. Atemporal Handwriting

Characteristics. Tendency toward experiences that transcend linear temporal logic: peak states, mystical insights, transpersonal episodes.

Theoretical meaning. A source of meaning-making and creativity; without adequate supports — risk of disorientation. It requires careful therapeutic integration.

In practice, handwriting rarely fits neatly into a single cell of the matrix; more often we are dealing with a dominant pattern accompanied by several secondary features. The matrix provides working hypotheses that require empirical validation.

5. Ornament as the «External Signature» of Handwriting — Hypothesis and Methodological Directions

Culture is not a neutral background: it codes rhythms, and ornament is one of the most evident forms of such coding. Ornament presents rhythm in visible form: repetition, interval, density, openness/closure of form. Hence a natural, tentative transition: if a personality has a stable handwriting, and if culture fixes rhythms, then ornament may carry traces of the handwriting of both individual and epoch.

Working hypothesis. Extraverted handwriting is more often expressed in open linear ornaments (waves, rows, flows), introverted — in closed, centripetal ornamental structures (circles, concentric compositions). Accelerated handwritings yield small, dense rhythms; slowed ones — large, «stretched» motifs.

Methodological paths for testing the hypothesis:

— Collecting a corpus of ornaments (ethnographic and contemporary design) and classifying formal characteristics (closed/open, density, rhythmicity, modularity).

— In parallel — psychological surveys and screening of temporal handwriting in creators / bearers of these ornaments.

— Statistical analysis of correlations: preference for forms ↔ handwriting indicators.

— Cross-cultural testing and contextual work: recognizing that ornament is culturally conditioned and may express a collective font rather than purely individual handwriting.

Ethical and methodological caveats.

Ornamental diagnostics is an auxiliary tool, not a substitute for clinical assessment. One cannot directly interpret a preferred pattern as a diagnosis; context, symbolism and tradition must be taken into account.

6. Theoretical and Empirical Implications: Directions for Further Work

The concept of temporal handwriting opens several avenues for research and practice:

— Cognitive-neurobiological correlates.

— Which neurophysiological parameters (HRV, cortisol profile, circadian markers) correlate with handwritings? One may expect clearly marked circadian patterns in rhythm-sensitive handwritings.

— Development and formation of handwriting.

— How do childhood, parenting modes, trauma, educational practices and cultural context shape handwriting? The role of epigenetics here is an important hypothesis.

— Clinical validation.

— Testing how well handwriting diagnostics predicts responses to specific interventions (chronotherapy, cognitive restructuring, mask-therapy).

— Cultural semiotics.

— Exploring ornamental and artistic manifestations of handwriting as part of cultural history.

7. Ethical, Clinical and Methodological Limits

— Avoid reductionism: handwriting is not a diagnosis but a description of rhythmic features.

— In the presence of severe pathology (psychosis, acute suicidality), avoid provocative projects without clinical preparation.

— When working with cultural symbols, maintain respect and avoid universalism (take local meanings of patterns into account).

— Any diagnostic procedure must be validated and aligned with ethical research standards.

8. Conclusions and Link to the Rest of the Book

Temporal handwriting is a central construct linking the philosophy of time with applied psychotherapy.

This chapter provides the conceptual foundation: handwriting is the signature of time in the psyche, formed by biorhythms, culture and archetypes.

Further on we will develop this idea: in the Appendix to Chapter 1 you will find a brief practical screening sheet; in Part II (especially Chapter 21) — the «Face of Personality» method and detailed mask-therapy techniques that use the notion of handwriting in practice.

___

Literature and Commentary

The following list brings together the philosophical and psychological texts underlying the theoretical core of this chapter, as well as contemporary directions in empirical research on time. For further study of temporal handwriting, works on the phenomenology of consciousness, the cognitive neuroscience of time, chronobiology and the epigenetics of rhythms are recommended.

Bakhtin, M. M. — «Forms of Time and Chronotope in the Novel» (1937–1938)

Shows how artistic forms record temporal structures of experience; an example of ornamental and narrative coding of time in culture.

Bergson, H. — Matter and Memory (Matière et mémoire, 1896)

A foundational work on inner duration (durée); distinguishes phenomenological time from physical measurement.

Buonomano, D., & Eagleman, D. — The Brain and Time (2009)

Reviews neural mechanisms of time perception; demonstrates how the brain constructs duration and sequence.

Frankl, V. — Man’s Search for Meaning (1946)

Highlights the centrality of future orientation in human motivation; relevant for the projective dimension of temporal handwriting.

Freud, S. — The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung, 1900)

Explores how the past continues to live in the present; psychoanalysis as an «archaeology of time.»

Grof, S. — The Holotropic Mind (1992)

Empirical foundation on altered states and transpersonal experiences; essential for atemporal dimensions of the psyche.

Husserl, E. — On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time (1905)

A classic analysis of the lived «now,» retention and protention; foundational for temporal structure of consciousness.

Jung, C. G. — Psychological Types (1921); Synchronicity (1952)

Typology supporting the axes of temporal handwriting; synchronicity introducing supra-temporal connections.

Kleitman, N. — Sleep and Wakefulness (1939)

Classic research on sleep–wake biological rhythms; base for chrono-aspects of handwriting.

Kravchenko, S. A. — Temporal Psychology (2017); works on the «Face of Personality» (2020–2025)

Authorial corpus forming the methodological and clinical base of temporal psychotherapy.

Maslow, A. — Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences (1964)

Describes peak experiences as atemporal states with developmental significance.

Plato — Timaeus (c. 360 BCE)

Foundational concept of time as an «image of eternity»; philosophical basis for temporal categories.

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. — «The Evolution of Foresight» (2007)

Evolutionary theory of mental time travel; highlights the unity of memory and imagination of the future.

Wittmann, M. — Felt Time (2016)

Neuropsychological study of subjective time; links temporal perception with emotional and bodily regulation.

Review studies on chronobiology and epigenetics (20th–21st centuries)

Show rhythmic inheritance and biological underpinnings of temporal organisation.

Chapter 2. The Anthropic Principle, the «Cosmic Human» and External Rhythms

Summary

The human being is not an abstract subject: we are rooted in a web of external rhythms — from the daily light–dark cycle to multi-year waves of solar activity and economic cycles. This chapter combines philosophical reflection (the anthropic principle, the metaphor of the «cosmic human») with an applied view: which levels of external rhythms have clinical and diagnostic significance for temporal psychology, how they can be tested, and how to treat cultural corpora (astrology, myth). The chapter stresses methodological caution: metaphors broaden our view, but empirical claims require rigorous testing.

Key Concepts

Anthropic principle (psychological reading) — the idea that the parameters of the world are «pre-tuned» in such a way that an observer can appear here; in a psychological reading, a working hypothesis about the attunement of the psyche to external rhythms.

Cosmic Human / Adam Kadmon — a metaphor of the unity of macrocosm and microcosm; phenomenologically rich and clinically usable as an image, but not empirically valid without testing.

External rhythms — cycles outside the individual: daily (circadian), lunar, seasonal, multi-year (solar activity), long-term historical/economic waves.

Zeitgebers — external «conductors» of biorhythms (light, social schedules, etc.); key to understanding why «biorhythms» are at once internal and externally relevant.

Methodological caution — distinguishing between metaphor, phenomenological corpus and testable hypothesis.

Aims of the Chapter

— To explain why discussion of external rhythms is important for temporal psychology.

— To describe five key levels of external rhythms relevant for clinical work and research.

— To provide recommendations for testing hypotheses about attunement between psyche and external rhythms.

— To clearly distinguish the cultural-symbolic domain (astrology, myth) from the empirical field of research.

Main Text

1. Philosophical Reflection: The Anthropic Principle and the «Cosmic Human»

In physics, the anthropic principle points out that the laws of the world are such that an observer is possible within it. A psychological reading of this idea is not a magical claim, but a way of posing the question: how do the properties of the surrounding world and its rhythms form the field in which the psyche arises and develops?

The metaphor of the «cosmic human» (Adam Kadmon and analogous images in different traditions) offers a rich phenomenological material: it fixes an intuition of the person’s co-belonging with the cosmos. But it is important to separate metaphor from empirical assertion: in science we put forward hypotheses about attunement and test them against data.

Here we immediately turn to a practical angle: external rhythms act as «addresses» for an extraverted temporal handwriting (people oriented toward external cycles tend to react more strongly to these rhythms), whereas an introverted handwriting is more oriented to inner temporal dimensions. This distinction is a working hypothesis, not a dogma.

Critical remark: always distinguish the context — philosophical (the metaphor of the «cosmic human») versus empirical (correlations between rhythms and mental state). Metaphor widens our view, but does not replace data.

2. Biorhythms as Both Internal and External

It is important to clarify: «biorhythms» are endogenous oscillators of the organism that are internally generated but entrained by external zeitgebers (light, temperature, social schedules). In other words, biorhythms are internal in origin but externally modulated; therefore the boundary between «internal» and «external» in rhythms is always relative. Contemporary work in circadian biology and its impact on health and mental functioning provides detailed support for this position.

3. Five Key Levels of External Rhythms

(clinical observations and verification)

Below is a working overview of levels useful for clinicians and researchers. For each, we sketch clinical observations and suggest avenues for verification.

3.1. Daily (Circadian) Rhythms

Phenomenon. The 24-hour organisation of sleep/wake, hormonal fluctuations and circadian patterns of activity.

Clinical picture. Variability of mood and performance across the day; morning apathy in depressed patients; suicidal and cardiac peaks in the early morning — clinically relevant markers.

Verification. Actigraphy, hormonal profiling, collecting time-stamped data on events (hospitalisations, cardiac episodes). Modern reviews highlight the major impact of the circadian system on health and immunity.

3.2. Monthly / Lunar Cycles

Phenomenon. The 29.5-day lunar cycle; historical beliefs about its connection with menstrual, behavioural and criminal patterns.

Clinical picture. Patients sometimes report insomnia or increased emotional lability during full moon; at the regional level some reports have described rises in emergency calls.

Verification. Prospective actigraphic and registry studies. There is robust prospective evidence for effects of lunar phase on sleep onset and duration, but meta-analytic reviews point to mixed findings and high sensitivity to methodology and sampling. Prospective registration and careful control of retrospective reporting are necessary.

3.3. Seasonal / Annual Rhythms

Phenomenon. Annual variations in day length, temperature and associated behavioural and biochemical shifts.

Clinical picture. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is the classic example; the efficacy of light therapy has been clinically demonstrated.

Verification. Clinical trials of light therapy; population-based studies of seasonal patterns in morbidity and birth rates.

3.4. Multi-year Cycles of Solar Activity (~11 years) and Geomagnetic Disturbances

Phenomenon. Cycles of solar activity, flare events and subsequent geomagnetic disturbances.

Clinical / societal picture. Retrospective analyses have found correlations between solar activity peaks and changes in acute medical utilisation, cardiac and psychiatric statistics; epidemiological work has shown associations between geomagnetic disturbances and increased mortality on some indicators.

Verification. Longitudinal multicentre studies that link satellite indices (Kp, sunspot number) with clinical registries. Existing studies show carefully derived associations, but the mechanism remains contested and requires replication.

3.5. Long Historical / Economic Waves

Phenomenon. Decades-long cycles in the economy, technological development and public mood (long-wave theories, Kondratiev and his successors).

Psychological significance. Mass temporality — collective expectations, perceived risks, readiness for innovation — generates societal scenarios that become embedded in individual life plans (career, family, migration).

Verification. Interdisciplinary studies combining historical data, sociological surveys and psycho-demographic measures. Methodologically this is a demanding but promising area.

Important caveat. Observed correlations at these levels do not equal proof of causality. Each association demands strict control for confounders and prospective registration.

4. Attitude Toward Astrology and Cultural Traditions

Astrological systems represent a large phenomenological corpus: centuries of observation, symbolism and interpretive technique. For temporal psychology they may serve as a phenomenological resource — a source of observations and meaning maps — but cannot automatically be treated as an empirical causal model without testing.

Put differently: astrology can be legitimately used as a cultural and therapeutic repertoire (working with symbol and meaning), but its postulates require verification if one wishes to claim scientific explanatory power.

Methodological recommendation. Use astrological and mythological motifs in therapy as metaphors and semiotic tools, but do not let them replace clinical diagnosis and statistical testing of hypotheses.

5. Hypotheses for Interdisciplinary Testing

(directions for research)

Below is a brief list of operational hypotheses that should be tested prospectively and with preregistered protocols:

— Circadian dysregulation correlates with increases in acute psychiatric exacerbations (to be tested via actigraphy and hospitalisation registries).

— Lunar phase modifies sleep parameters in sensitive individuals (prospective actigraphy under controlled conditions).

— Geomagnetic disturbances are associated with changes in the rates of acute events (lag analysis, multilevel modelling, satellite data).

— Long socio-economic cycles influence collective temporal scenarios that, in turn, shape individual decisions (historical-psychological research).

Each of these hypotheses is a candidate for prospective multicentre projects with preregistered protocols.

Practical Tool — Mini-Questionnaire

«Connected with Rhythms» (5–7 minutes)

(Use as a screening instrument; positive answers are a reason to deepen the temporal profile.)

1. Do you notice changes in your mood at different times of day? (never / sometimes / often)

2. Do you experience insomnia or worse sleep during full or new moon? (no / sometimes / yes)

3. Do you have seasonal fluctuations in mood/energy? (no / moderate / pronounced)

4. Have you noticed any link between your dreams and major external events (disasters, accidents)? (no / sometimes / yes)

5. Do you experience periods when «time falls out» — meaning seems to stop? (no / sometimes / often)

6. Do recurring family scenarios appear across generations? (no / a few / many)

7. Is your sleep disrupted when you change time zones or work schedules? (not at all / moderately / strongly)

Instruction for the therapist.

Answers such as «often / yes / pronounced / strongly» are a reason to expand the assessment of temporal handwriting (see Chapter 1) and, if appropriate, to compare events with external indicators (lunar phase on the date of the event, local weather/seismic data, Kp-index). Full diagnostic tools are presented in Part II and in the Appendix to Chapter 2.

Transition to the Next Chapter

In Chapter 1 we introduced the concept of temporal handwriting; in Chapter 2 we have added the layer of external attunements. The next chapter (Chapter 3) examines inner rhythms and the issue of the psyche stepping «beyond» material connections — atemporality and altered states of consciousness.

Kondratiev Waves and Psychological Adaptation to the Technological Epoch

Kondratiev waves are long cycles (approximately 40–60 years) describing regular fluctuations in the development of the global economy and technology. Each wave begins with a technological breakthrough that gradually permeates the entire society, changing not only production but also lifestyle, culture, modes of communication and thinking. After a phase of rapid growth come saturation, crisis, decline and the preparation of the next wave. Traditionally these macroeconomic rhythms were described with reference to economic processes, but their impact on psychology and human development remains understudied.

If we accept that the human being lives inside the rhythms of the epoch — technological, economic, cultural — then an individual biography is inevitably «inscribed» into these large-scale oscillations. Depending on the phase into which a person is born and in which they form, they may end up either in resonance or in dissonance with the dominant technologies of their time.

Synchronous Generation

Those born at the beginning of a new technological wave (for example, children of the 1990s–2000s during the digital upswing) develop together with the technological environment. They absorb innovations naturally, playfully. For them, digital, networked and hybrid thinking is the norm. Their psychology is «synchronous» with the epoch, and their inner rhythms coincide with external ones.

Transitional Generation

These are people whose childhood or youth falls on the boundary between technological regimes — for example, those born in the 1960s–70s who lived through the shift from an industrial to a digital world. They often have a split perception: on the one hand, a habit of a stable world of material things; on the other, a forced adaptation to abstract, networked, virtual structures. They often become bridges between epochs but also experience inner tension between the old and the new type of consciousness.

Asynchronous Generation

Particularly vulnerable are those born in the downturn phase, when the previous technological order is dying and the new one has not yet taken shape. Their skills and values become «orphans of the epoch»: they think in categories of yesterday’s world, while reality already demands a different logic. We see this especially clearly today: older or middle-aged people who have not managed to master digital technologies feel «fallen out of time.» They lose access to information, services and social connections. Lagging behind becomes not only technical but existential: a sense of being «unneeded» and «not contemporary» generates anxiety, shame and devaluation.

The Psychotherapeutic Dimension

The task of psychotherapy is to help the person restore synchrony with the epoch — not in the sense of imitating technologies, but by understanding their own temporal rhythm and accepting their place in the overall flow of history. For asynchronous personalities it is essential to recognise that their experience and depth belong to another phase of the wave — and precisely for that reason may be valuable: they carry the «memory of the previous cycle,» which is needed for balance and continuity.

Work with such clients includes:

— reducing guilt and shame about «lagging behind»;

— becoming aware of one’s own «temporal biography» — where one is located in the rhythms of the epoch;

— finding forms of participation in contemporary life without losing one’s identity;

— developing cognitive flexibility and tolerance of uncertainty characteristic of new technologies.

For transitional generations, psychotherapy helps integrate the double experience: to preserve inner supports from the old world and master new symbolic forms (virtual interaction, digital creativity, network ethics). For synchronous generations, conversely, the emphasis is on slowing down and forming deeper self-awareness, in order to avoid superficiality and fragmentation of digital time perception.

Thus, Kondratiev waves can be seen not only as macroeconomic regularities but also as rhythms of anthropic time that shape psychological types of the epoch. Understanding these rhythms opens a new perspective on individual destinies and crises — as reflections of the great oscillations of global civilisation.

Literature

Babones, S. — Global Kondratiev Waves and Political Transformations of World Systems, 2019.

Analyses how long economic cycles correlate with political shifts and transformations of world systems. Useful for extending long-wave logic to cultural and psychological change across generations.

Casiraghi, L., Spiousas, I., Dunster, G. P., et al. — «Lunar Sleep: Synchronization of Human Sleep with the Lunar Cycle under Natural Conditions,» 2021.

A prospective actigraphy-based study showing associations between lunar phases and changes in sleep onset and duration. Provides convincing empirical evidence that calls for replication across populations and settings.

Devezas, T. C. — «Biological Determinants of Long Waves of Socio-economic Growth,» 2015.

Explores analogies between biological rhythms and economic long waves. Offers a theoretical basis for the metaphor of «epochal generations» and for linking macro-cycles with human development.

Gaspel, J. A., et al. — «Perfect Timing: Circadian Rhythms, Sleep and Immunity,» 2020.

A modern review of interactions between circadian rhythms, sleep and immune function. Demonstrates systemic effects of daily cycles on health, stress resilience and mental state.

Glazyev, S. Yu. — Theory of Long-Term Techno-Economic Development, 1993.

A classic Russian exposition of long-wave theory in the context of technological paradigms. Important for understanding how technological shifts shape social structures and temporal experience.

Grinin, L. E. — Kondratiev Waves, Technological Modes and the Theory of Production Revolutions, 2012.

Shows the links between long waves and phases of technological development, describing how each wave creates a new type of society. Provides macro-historical context for technological epochs.

Kondratiev, N. D. — Long Waves in Economic Life, 1925.

The foundational work on long cycles in economic dynamics. Introduces the idea of long waves that later became a key framework for analysing technological and social rhythms.

Kravchenko, S. A. — Temporal Psychology and Psychotherapy: The Human in Time and Beyond, in progress.

Develops the idea of the person’s inner synchronisation with external rhythms — from biological to civilisational. In this framework, Kondratiev waves are interpreted as manifestations of a broader cosmic rhythm influencing psyche and destiny.

Litinski, M., et al. — «Impact of the Circadian System on Disease Severity: A Review,» 2009.

Epidemiological and clinical review showing how time of day and circadian phase affect disease outcomes. Supports the concept of «circadian medicine» relevant for temporal clinical practice.

Nefiodov, L. — The Sixth Kondratiev Wave: The New Long Wave of the World Economy, 2014.

Discusses the current digital-biotechnological cycle, in which the human being becomes part of the technological system rather than just a consumer. Important for understanding psychological pressures of the present wave.

Nishimura, T., Tada, H., Nakadani, E., et al. — «Stronger Geomagnetic Fields as a Possible Risk Factor for Male Suicide,» Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 2014.

A regional study showing a possible association between geomagnetic field intensity and male suicide rates. An example of carefully conducted analysis that nonetheless requires replication.

Rönneberg, T. — «The Circadian System, Sleep and the Balance of Health and Disease,» Journal of Sleep Research, 2022.

Conceptual review that frames the circadian system as a central regulator of health and disease. Helps situate temporal clinical work within the emerging field of circadian medicine.

Rosenthal, N. E., Sack, D. A., Gillin, J. C., et al. — «Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Description of the Syndrome and Preliminary Findings with Light Therapy,» Archives of General Psychiatry, 1984.

First clinical description of seasonal affective disorder and the use of light therapy. A foundational study that launched modern chronopsychiatric approaches.

Rotton, J., & Kelly, I. W. — «Much Ado about the Full Moon: A Meta-analysis of Lunar-Lunacy Research,» Psychological Bulletin, 1985.

A classic meta-analysis showing the methodological fragility and ambiguity of claimed lunar effects. Emphasises the need for rigorous prospective designs and cautions against retrospective myth-making.

Tulin, A. E., & Chursin, A. A. — «Developing Kondratiev Long-Wave Theory: The Place of AI Economy and Humanisation of Competences,» Philosophy of Science and Technology, 2023.

Highlights artificial intelligence as a key factor in the sixth long wave and discusses changes in human competences in the AI epoch. Useful for linking technological trends with shifts in temporal experience and identity.

Vieira, S. L. Z., Alvarez, D., Blomberg, A., Schwartz, J., Kautz, B., Huang, S., & Koutrakis, P. — «Solar-Induced Geomagnetic Disturbances and Increased All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in 263 US Cities,» Environmental Health, 2019.

A large epidemiological study revealing correlations between geomagnetic disturbances and increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Provides material for hypotheses about cosmic influences on health.

Wirtz-Justice, A. — «Seasonality in Affective Disorders,» 2017–2018.

A modern overview of mechanisms behind seasonal mood fluctuations and hormonal cycles. Underlines the importance of chrono-therapeutic strategies in psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Chapter 3. Inner Rhythms and the Limits of Connection with Time

Summary

This chapter immerses the reader in the world of the psyche’s inner rhythms — in how the person experiences the present, how the past resounds in the present, and how the future shapes the direction of life. We introduce the notion of an inner (introverted) temporal handwriting and examine three dimensions of time in the psyche: present, past and future. Special attention is given to altered states of consciousness (ASCs), through which the psyche can temporarily step beyond its usual rhythmic conditioning, and to the practical implications of this for therapy.

Key Concepts

— Temporal handwriting — an individual, characteristic way of experiencing time; an integration of biorhythms, cultural rhythms and personal modes of narrating one’s life. Components: biorhythms / external rhythms (lunar, seasonal, social) / narrative organisation (how a person tells their own story). Manifestations: speech tempo, attention to the «here,» frequency of retraumatisation, tendency toward premonitions. Practical assessment: questionnaires, time-stamped diaries, observational markers (speech tempo, degree of contact), actigraphy.

— Present (temporal «here-and-now») — the convergence point of experience, the field where subpersonalities meet and choices are made.

— Past — a storage of experience, memory, ancestral and cultural traces that resonate in the present.

— Future — projections, intentions, projects and unconscious outlines of expectation.

— Altered states of consciousness (ASCs) — modes of experiencing in which linear time weakens; a source of experiences of timelessness and eternity.

— Atemporality / time-void — different shades of experience in which ordinary chronology loses its primacy: from emptiness and apathy to peak insight.

Aims of the Chapter

— To formulate and justify the idea of inner dimensions of time — present, past and future — as distinct levels of experience and regulation.

— To show how temporal handwriting integrates these dimensions and how it is shaped by biorhythms, culture and personal history.

— To consider ASCs as a mechanism of temporary freeing from usual temporal conditioning and as a therapeutic resource, provided there is preparation and integration.

— To provide practical guidelines for assessing and working with inner rhythms in clinical practice.

Introduction — the Next Step

In Chapter 1 we became acquainted with the concept of temporal handwriting — a stable way of living in time. In Chapter 2 we expanded the picture by adding the external layer: the synchronisation of the person with cosmic (solar–geomagnetic), natural (daily, seasonal) and socio-historical rhythms. Now our path leads inward: to how the psyche itself constitutes time — how it experiences the present, stores the past and lives through the future.

The inner world is where the introverted temporal handwriting is especially vivid. For an introvert, biorhythms and inner cycles are not just physiology but the fabric of meaning: sleep rhythms, mood arrhythmias, cycles of memories and premonitions form the rhythmic handwriting of inner life. Even for an extravert, inner rhythms are always present and interacting with external ones; the difference lies in the direction of sensitivity.

The question of the boundary between predetermination and freedom in time is central for temporal psychology. Where is the line between what «is given to us» (biorhythms, ancestral scripts, cultural codes) and what we can change — through practice, through attention, through work with symbol? This boundary is marked precisely at the points where the psyche transitions into other modes — altered states of consciousness. In ASCs, human experience goes beyond linear sequence: past, present and future cease to be separate coordinates, and another kind of fabric of meaning arises.

Three Dimensions of Inner Time: Present, Past, Future

1. The Present — the Field of Assembly