Бесплатный фрагмент - The Secrets of the Two-Faced Maiden. Part 3

РАКЕ 3 Mysteries of origin, mysteries of the past, and tragedies of the present

2005–2007. The Revelation of Her Origins

The long-awaited year 2005 began. Natalia hoped that all her troubles with the criminal world were finally behind her, and with them the danger to her life. In her heart, she still cherished the hope for a happy future. She was already 36 years old. Natalia was well aware that due to her spinal condition, pregnancy and childbirth would be extremely difficult for her. Nevertheless, she felt it was time to seriously think about finding a husband and having children. Yet she recalled with bitterness the story about the criminals’ search for a girl who had three life lines on her palms, and the fortune-telling connected with it. Natalia could not forget the words that “the girl is of very high origin — even royal.”

The only thing Natalia knew at that time about her father’s lineage was that her paternal ancestors had been well-to-do peasants who were dispossessed during the collectivization. Her grandfather, Pavel Yefimovich (her father’s father), perished in captivity during the war in 1941. According to her grandmother Pelageya, Natalia also knew that after the war, a letter “I” was added to her grandfather’s surname — supposedly by accident — during the restoration of documents that had been destroyed in the war.

Natalia’s father was raised by his mother, Khazanova Pelageya Afanasyevna (born in 1913, died in 1982), together with her younger sister Khazanova Irina Afanasyevna (born in 1922, died in 2004), who had never been married and had no children of her own. They lived in the village of Sherstin, in the Vetka District of the Gomel Region. After finishing the local school, Natalia’s father left for the city of Gomel to study — and remained there to live. Natalia found it strange that she had never seen any relatives on her grandfather’s side — the Zbitskys (or Izbitskys). She often asked her father about them, but he always gave evasive answers or changed the subject. The only thing Natalia knew was that her grandfather had come from the village of Akshinka in the Gomel Region. She also knew that her father had an older brother and sister, but they had died during the war. Her father barely remembered them.

When Natalia and her sister lived with their grandmother, Irina Afanasyevna, before the criminal events of 2004, she decided to learn more from her about the war and their relatives. Natalia had previously heard from her other grandmother, Pelageya, that as soon as the war began, grandmother Irina joined the partisans so that she would not be sent to a concentration camp in Germany.

However, grandmother Irina Afanasyevna refused to tell Natalia about her partisan life, saying that it was better for her and her sister not to know about it. Natalia then asked her grandmother Irina about her grandfather and about her father’s brother and sister. What Irina told her left Natalia completely shocked. Grandmother Irina told Natalia that grandmother Pelageya had never had children of her own. She was a widow from her first marriage, while grandfather Pavel Yefimovich married her and brought with him three children, saying they were his nephews. The boy’s name, apparently, was Pyotr; he was about five or six years old. The girl was about ten and was called Shurka, or more often Sashka. She was fair-haired and very intelligent. Grandfather Pavel Yefimovich was also very educated and knew absolutely nothing about farm work. He had returned from prison in 1939, having served time as a political prisoner. Over the next two years, he gradually learned how to do peasant labor, but he never went to work in the collective farm — he only worked for himself. He was about two meters tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed, and possessed incredible, almost heroic strength. When the traveling food store came to the village, he never stood in line — he always went straight to the front. Former prisoners (mostly political ones) from all over the USSR came to visit him, especially often from Moscow, and the entire village was afraid of him.

Grandmother Irina also told Natalia that grandfather Pavel Yefimovich had not died at the front — in fact, he had never gone to serve in the Soviet Army. For this, at the beginning of the war (in 1941), he was executed by partisans in his own garden — and that’s where he was buried. The boy Pyotr suffered from a blood disease; he was very weak and, toward the end of the war, was injured. Within a few days, he slowly bled to death. Neither doctors nor healers were able to stop the bleeding. The girl Sasha died in 1944 during a diphtheria epidemic at the age of about twelve or thirteen. Grandmother Irina also said that her own parents, on the Khazanov side, had been very wealthy — they owned much land and many fields — but after the Revolution, everything was taken away from them.

After this conversation, Natalia and her sister decided to talk to their father about what they had learned from grandmother Irina. But their father replied that the old woman was just imagining things. Natalia thought that perhaps her grandmother had begun to suffer from senility. Yet the thought that her own grandfather had been buried like a dog in a garden in the village of Sherstin would not leave her in peace. This conversation took place in 1998. Natalia’s father generally disliked talking about his childhood or relatives, as if he remembered nothing at all. The only thing he told her was that once, before joining the army, grandmother Pelageya had taken him far beyond the village of Sherstin to visit some elderly woman, without telling him who she was. That was the first and last time he saw her, as far back as he could remember. He saw an old, sick, completely blind woman — thin and small. He and his adoptive mother stayed with this old woman for about three or four hours. The blind woman cried bitterly the entire time, sobbing as she touched his face and body with her hands, and he could not calm her down. Some time later, he left to study in the city of Gomel, and afterward went to serve in the army. While in the army, he learned that the blind old woman had died. This was in 1956–1957.

The Vision of the Mother of God to Natalia’s Father, Nikolai Pavlovich

Natalia’s father, Nikolai Pavlovich, remembered only two significant events from his childhood and youth. The first was when, at the age of sixteen, he experienced an apparition of the Mother of God in the village of Sherstin. It was an ordinary winter day, with deep snow and a severe frost of more than 25 degrees below zero. At around ten in the evening, he went outside to relieve himself — the village toilet was located in the garden behind the yard. When he stepped out of the toilet to go back to the house, a powerful light suddenly shone behind him. He turned around — and froze in place. Before him, suspended in the air, stood a woman about ten meters tall, clothed entirely in white, radiating an intense white light. She said to him:

“Do not be afraid of Me. I will protect you throughout your life so that nothing ever happens to you. No one will be able to destroy you physically. As for those enemies who stand in your way and who will be mortally dangerous or will cause you harm — I will remove them. They will not live more than a year. Fear nothing that life brings you — I will protect and preserve you and your children. Evil will come near you, but it will not harm you greatly.”

After these words, Natalia’s father lost consciousness. His adoptive mother, Pelageya Afanasyevna, found him only in the morning. He was lying unconscious on the ground, and within a radius of about three meters around him, all the snow had melted and the earth was warm. They carried him into the house and managed to revive him. Everyone was astonished that, despite lying all night in the freezing cold, he had not frozen to death or even caught a cold. At that time, it was the Soviet era, and speaking about such apparitions was forbidden and dangerous. Therefore, the family concealed the incident as best they could. Only after the fall of the Soviet regime did Natalia’s father tell Natalia and her sister about it for the first time.

An Incredible Healing from Burns

The second event happened during his military service, where he worked as a driver. One winter day, a bucket of gasoline caught fire under his vehicle. He pulled the bucket out from under the car, but in doing so, he splashed himself with the burning fuel and caught fire. His fellow soldiers extinguished the flames by covering him with snow, but from the pain, he lost consciousness. His face, hair, and hands were severely burned — his hands were almost reduced to bone. Yet within a month, everything healed completely, leaving not a single scar.The only trace that remained was on one of his palms, where several lines had disappeared — the skin was perfectly smooth. The military doctor who treated him showed him to other doctors as an extraordinary case, saying that he had never seen anyone recover so completely after such severe burns. He called it nothing short of a miracle.

A Fateful Meeting with Pyotr Vashchenko and His Daughters

Several years later (in 2000), the wife of Pyotr Vashchenko — an army comrade of Natalia’s father (who passed away in November 2007) — died. She had been the godmother of Natalia’s brother, Alexander. Natalia’s parents had frequently met with the Vashchenko family in the past, but during the Perestroika period (1989–1999), they had virtually no contact with them. Pyotr Vashchenko had two daughters: Olga (born in 1965) and Yelena (born in 1970). Natalia’s parents met the Vashchenko family again for the first time in many years at the funeral of Pyotr’s wife, after which they began interacting more closely.

At the funeral, however, an extremely unpleasant incident occurred. Several people among Vashchenko’s friends stared strangely at Natalia’s father, her mother, and Natalia herself along with her sister. Natalia’s brother was not present at the funeral. Natalia even felt uncomfortable under those stares — it seemed as if they were looking at her family as though they were aliens. The funeral took place in a village located within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. When passing through the police checkpoint, the officers even demanded that the coffin be opened to verify that they were indeed transporting a body for burial and not entering the restricted area for other reasons.

Both of Pyotr Vashchenko’s daughters were unmarried at the time. Yelena Vashchenko was seven months pregnant, while Olga had suffered a nervous breakdown following her mother’s death and was hospitalized in a psychiatric facility. Natalia and her sister often visited them and offered help. Natalia knew that Pyotr Vashchenko came from the village of Akshinka — the same village as her own grandfather, Pavel. Seizing the opportunity, she decided to ask him about her grandfather. Pyotr Vashchenko began speaking to Natalia and her sister in an almost hushed voice about their family origins. He was deeply surprised that they knew nothing about their roots. He confirmed that Grandfather Pavel had actually been killed by partisans, not died during World War II as Natalia had been told. He added that Pavel’s grave was still located in the garden of their house in the village of Sherstin. Pyotr also mentioned that their grandfather came from such a distinguished lineage that even when they fell into poverty, they never wore bast shoes (lapti) — they always wore boots.

However, he noted, compared to their grandmother, Grandfather Pavel’s origins were insignificant, because she — Nastenka — was a Romanova from Moscow. At that moment, neither Natalia nor her sister Yelena paid much attention to the grandmother’s surname, “Romanova,” as they had no idea what Pyotr Vashchenko truly meant — after all, “Romanov” was a fairly common surname in the former USSR. Natalia’s full attention was focused solely on the fate of her grandfather, Pavel Yefimovich. She now understood that her grandmother Irina had told her the truth. Yet she couldn’t comprehend why her own father continued to deny these facts. After speaking with Pyotr Vashchenko, Natalia again asked her father about Grandfather Pavel, but once more her father insisted that his father had died at the front.

From that day on, Natalia began seriously reflecting on her grandmother Irina’s earlier words — about a boy named Pyotr who had died of hemophilia, about a girl named Sasha, and about adopted children. However, by then there was no one left to ask for answers: in 2000, Grandmother Irina had suffered a stroke and was diagnosed with senile dementia (Alzheimer’s-type cognitive decline). She now barely recognized Natalia, constantly confused people and events, and could no longer provide coherent information. More than four years passed after Natalia’s conversation with Pyotr Vashchenko. By this time, Natalia had connected to the Internet for the first time and started browsing prophecies and predictions about the future. Living in Belarus, she had paid little attention to events in Russia — especially after the collapse of the USSR, when survival itself demanded all her energy and effort.

While browsing various news articles online, she learned for the first time that the family of Emperor Nicholas II had been canonized by the Orthodox Church. She also discovered the story of the “Yekaterinburg remains,” specifically that two bodies had not been found in the grave — and that one of the Romanov daughters, either Maria or Anastasia, might have survived. Reading these articles was deeply distressing for Natalia. She skimmed them superficially and decided not to read any further. Yet the words of the clairvoyant about the origin of the girl with a triple life line on her palms would not leave her in peace. One morning, upon waking up, Natalia suddenly recalled Pyotr Vashchenko’s words: “Compared to your grandmother, your grandfather’s lineage is nothing — she was Nastenka, a Romanova from Moscow.”

Natalia spoke with her sister, urging her to try to remember exactly what Uncle Pyotr had told them. Yelena told her that Vashchenko had clearly stated their grandmother’s name and surname: Anastasia Romanova.The first thought that crossed Natalia’s mind was: “Please, not this.” She and her sister decided to proceed by a process of elimination. Natalia called Pyotr Vashchenko and arranged to meet him. During their meeting, she asked him once again about her grandmother. Pyotr Vashchenko confirmed that Natalia’s father’s biological mother was indeed Anastasia Romanova, the youngest daughter of Emperor Nicholas II.

However, Pyotr Vashchenko said to Natalia and her sister:

“Girls, why do you need this? Everyone has already forgotten about it…”

Pyotr Vashchenko explained that his own grandfather — a devout Old Believer — had revealed to him, shortly before his death and long before Perestroika, the secret of Natalia’s father’s origins and the fate of Anastasia Romanova. This grandfather had lived with Anastasia Romanova in the forest until her death. He also mentioned that one of his relatives — either his grandfather or his father — had served as the estate manager for Anastasia’s husband. Furthermore, he said that sometime between 1935 and 1937, someone betrayed her, and Grandmother Anastasia was targeted for assassination — but she survived. Afterward, she went into hiding in the forest, and her children were taken in and raised by Grandfather Pavel Yefimovich after he was released from prison.

Natalia also learned from Pyotr Vashchenko that Anastasia’s husband had buried a treasure and burned down the estate so it would not fall into the hands of the communists.

A Strange Incident Involving Alexander Kovalev in 1998

Natalia also recalled another unsettling episode from her life in August 1998, involving her former friend Alla and Alla’s live-in partner, Alexander Kovalev. Alexander called and urgently asked Natalia to watch a specific TV program discussing prophecies, mysteries, and revelations by psychics. At the time, Natalia and her sister were watching a comedy on another channel, but out of curiosity, they switched over. The program featured a segment about the recently discovered remains near Yekaterinburg, which had just been reburied in St. Petersburg. It also showed excavations at the site where the remains of Emperor Nicholas II’s family had been found. Leading psychics had traveled to the location to try to “read” the lives and fates of those buried in the grave. Almost all of them concluded that one of the imperial daughters had survived the massacre and lived to be 56–57 years old.

After watching this, Natalia and her sister inexplicably felt unwell. Natalia switched back to the comedy, but a clear thought echoed in her mind: “This story about the imperial family’s remains is connected to you.” After a few minutes of silence, Natalia decided to voice her thought aloud and asked her sister, “Didn’t it seem to you that this story has something directly to do with us?” To Natalia’s surprise, her sister Yelena asked her the exact same question at the very same moment. This often happened between them — they would say the same words or phrases simultaneously. Natalia looked at her sister in bewilderment. Afterward, they both decided it was just nonsense running through their heads, since neither she nor any member of her family could possibly have any connection to the murder of the imperial family.

The next day, Alexander called and asked whether Natalia had watched the program. She told him she hadn’t, explaining that the broadcast began with graphic descriptions of a brutal murder, which made her feel ill — she generally found it difficult to watch such content. At the time, Natalia didn’t understand why Alexander had so insistently urged her to watch a program about the investigation into the imperial family’s murder. But after learning from Pyotr Vashchenko that her father was the son of Anastasia Romanova and grandson of Emperor Nicholas II, Natalia realized that Kovalev had been testing whether she knew anything about her lineage or had any connection to the Romanov imperial family.

Memory Problems Affecting Natalia, Her Sister, and Her Father

Natalia and her sister decided to research Anastasia Romanova more thoroughly, typing “Anastasia Romanova” into a search engine. The first link they found described the case of the so-called “false Anastasia,” Natalia Petrovna Bilikhodze, who between 1996 and 2002 was promoted as the surviving Grand Duchess Anastasia. They then found information about Anna Anderson, another impostor who claimed from 1919 to 1984 to be the surviving Anastasia. Natalia resolved not to question her father about what Uncle Pyotr had revealed until she clarified everything herself, as she remembered another puzzling incident from the past.

In 2003, Natalia’s father was chopping firewood at their dacha and accidentally severely gashed his leg with an axe. He tried to hide the injury from his daughters, but Natalia noticed blood outside near the woodpile and ran to find him. When she located him, he was bandaging his leg himself. As a nurse with experience in a surgical ward, Natalia immediately recognized the wound as serious — deep enough to require surgical intervention. Yet her father flatly refused to go to the emergency trauma clinic. Natalia dressed the wound herself and bought all necessary medications. Two weeks later, however, the wound still hadn’t healed. Natalia feared her father might develop an infection or gangrene, but he continued refusing to see a surgeon, insisting it would heal on its own.

Finally, Natalia turned to a psychic acquaintance for help, asking her to treat her father remotely using his photograph. Upon looking at the photo, the psychic said Natalia’s father had a memory block. She explained she had seen such a block only once before — in a Moscow acquaintance who had worked for the KGB — but his had been weak, whereas Natalia’s father’s block was “very professionally done.” She added that only special services could perform such memory manipulation and advised Natalia to seriously consider why such a block might have been implanted — perhaps Natalia didn’t know something about her father’s past, such as whether he had served in secret military units or the KGB.

Natalia later learned that her father had served in the Soviet Army from 1957 to 1961 in the Strategic Rocket Forces. At that time, the USSR stood on the brink of nuclear war with the United States, the Berlin Wall was being erected, and the entire Soviet military was on high alert. Pyotr Vashchenko had served alongside Natalia’s father in a training unit, but they were later separated. After completing his term, Vashchenko returned home, while Natalia’s father was recalled for several additional months. During that era, soldiers could be flown to secret bases and later have their memories erased so they would remember nothing. Such technologies already existed at the time.

Only after learning about her true origins did Natalia realize that her father’s memory problems might have begun much later — and were directly linked to his lineage. She began seriously wondering: if special services had tampered with her father’s memory, could they also have interfered with the memories of her mother, brother, and even herself and her sister? Perhaps her brother’s behavior stemmed not so much from hatred toward his sisters and parents, but rather from psychic interference or hypnosis.

Discussing the situation with her sister Yelena, Natalia tried to recall memories from when she was 18 years old — but those recollections remained extremely vague. She remembered that at age 18, her father had revealed the secret of his origins to her, her sister, and her brother. Neither Natalia nor Yelena could clearly recall the details of what he had said — only the intense emotional reaction his words had provoked. In Soviet times, revealing such information could have cost one’s life. Although it was already 1987—the era of Perestroika and the beginning of the USSR’s collapse — the revelation was still profoundly shocking to Natalia and her sister. Naturally, once they learned the truth, they knew they had to remain silent.

Natalia also recalled several other unpleasant incidents from her school years around that time. She had been an excellent student and was expected to receive a gold medal; her sister fell just short of medal eligibility. However, whether due to Natalia’s illness or some other factor, the teachers’ attitude toward both sisters suddenly changed toward the end of 10th grade. Their final school certificates were filled with grades they had never received during the year — B’s for Natalia and C’s for her sister — despite consistently earning top marks throughout their schooling. The character references they received were so disgraceful they were too ashamed to show them to anyone.

Natalia chose not to contest the certificates; all she wanted was to finish school as quickly as possible and forget the whole experience like a nightmare. At the time, she cared far more about finally being able to walk without her back brace and without pain than about grades in a diploma.

Only now, many years later, did Natalia suddenly realize that the teachers’ sudden hostility might have resulted from deliberate interference by special services in her family’s life. This could have been triggered if Natalia’s brother had accidentally revealed the family secret in a drunken gathering — or if others who knew Anastasia Romanova’s fate had disclosed it. Even Pyotr Vashchenko’s daughters might, by that time, have learned their great-grandfather’s secret and inadvertently spread it among acquaintances. It was precisely during this period that Natalia’s father — and possibly other family members — could have had their memories blocked.

A Strange Encounter with the “Thief-in-Law” Igor Belov in 1990–1991

Natalia and her sister recalled another strange incident from their lives in 1990–1991. At the time, both worked as nurses in a children’s polyclinic. They had become very close friends with a colleague, Viktoriya Belova, and had even vacationed together in Dagestan in June 1990. Natalia later learned that Viktoriya’s father had been a highly influential criminal authority during Soviet times — a so-called “thief-in-law” (vor v zakone) and, in effect, the local “overseer” of the city’s underworld. Natalia and her sister rarely visited Viktoriya at home and had never met her father before. But one day, such a meeting did take place. Natalia saw Viktoriya’s father, Igor Belov, for the first time. He approached Natalia and her sister and, in an extremely rude tone, demanded:

— What’s your last name?

Natalia answered. Then Viktoriya’s father again asked, just as harshly:

— And where’s your grandfather? Why isn’t he doing anything? The Soviet regime has already collapsed — why is he staying silent?

Natalia replied that her grandfather Pavel had died at the front during World War II in 1941. After hearing this, Viktoriya’s father stood silently for a moment, then, still in the same brusque manner, asked:

— And where’s your father? Why isn’t he doing anything?

Natalia answered that her father worked as a shop foreman at a factory. She was deeply offended by the man’s tone. The conversation was interrupted by Viktoriya, who told her father they were late for the movies.

A second encounter with Viktoriya’s father occurred a couple of weeks later. It was a summer day in August. Natalia, her sister, and Viktoriya had arranged to visit a colleague — a doctor who was temporarily working at a children’s sanatorium in Chenki, just outside the city — with a male acquaintance who offered them a ride in his car. They stopped by Viktoriya’s apartment to pick her up. Natalia and her sister Yelena went inside and once again saw Viktoriya’s father. This time, he asked nothing. He simply stood there, looking at Natalia and her sister with a gaze filled with despair and profound sadness.

Natalia even asked Viktoriya whether her father was feeling well. Viktoriya replied that he had been suffering from frequent headaches lately. Natalia and her friends then drove off to the sanatorium. While they were visiting, someone stole Natalia’s bag from the car — containing her passport, money, and food ration coupons. At the time, this was a devastating loss: food coupons were issued per family member, and losing them meant Natalia would not receive her allotted share of essential groceries. Buying basic food items without coupons was impossible due to severe shortages.Although the visit itself was brief, Natalia and her companions spent the entire evening until late at night at the local police station, filing a report and giving witness statements.

When Natalia returned home with her sister after 11 p.m., Viktoriya called and told her that her father had hanged himself at home. Natalia was utterly bewildered. She couldn’t understand what had driven Viktoriya’s father to suicide — but deep down, she sensed it was somehow connected to her. She would forever remember that look of resignation, the sorrow and regret in his eyes, though she couldn’t grasp their cause.

A month later, Natalia obtained a new passport. But soon afterward, she was unexpectedly summoned to the police station and accused of stealing a large number of video cassettes from a video rental store. It turned out that fraudsters had used her stolen passport to rent numerous expensive tapes and never returned them. At the time, VCRs and video cassettes were extremely costly. However, since Natalia could prove her original passport had been stolen, the police dropped all charges against her.

Only many years later — after learning that her grandfather had a criminal record — did Natalia realize that Viktoriya’s father had known Pavel Yefimovich Zbitsky personally. Given their similar ages, they could easily have served time in the same correctional facility. Most importantly, Natalia came to understand that the criminal authority Igor Belov had clearly known the truth about her father’s origins and the secret of Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova’s fate.

Still, Natalia remained deeply troubled by the fact of his suicide. She couldn’t shake the thought that Viktoriya’s father might have been murdered — if he had revealed the secret he knew to someone. It wasn’t until 2010 that Natalia grasped another possible reason for his suicide. This explanation had nothing to do with the Romanov lineage but was instead tied to the consequences of Viktoriya’s own erratic behavior and a false accusation leveled against Natalia for a crime she did not commit. However, that is a separate story, which will be recounted in later chapters of this book.

Several years after her father’s death, Viktoriya Belova told Natalia that he had written a memoir about his life — and that her older brother, who lived in Ukraine, had sold it for a large sum of money. What exactly was written in those memoirs could only be guessed at. If Viktoriya’s father had mentioned his acquaintance with Natalia’s grandfather — and if he had recorded what he knew about who Natalia’s father truly was in relation to the Romanov imperial family — then Natalia could only hope that this information had not fallen into the hands of dangerous criminals or enemies of her family and lineage.

The Stories of False Anastasias Romanova Reveal Hidden Secrets and Crimes of Those Attempting to Claim the Imperial Inheritance

After studying in detail the cases of the most prominent impostors who claimed to be Anastasia Romanova, Natalia learned about the vast overseas inheritance of Emperor Nicholas II — estimated at billions of dollars — and the numerous attempts to steal this inheritance by promoting various false Anastasias. She also discovered the existence of the Romanov Imperial House abroad, headed by descendants of the Kirillovichi branch, and much more.

Having verified external physical similarities between herself, her family members, and representatives of the Romanov dynasty — as well as the British royal family, particularly Queen Victoria — Natalia finally understood why, during a visit to the Louvre in 2001, passing tourists paid more attention to her and her sister than to the artworks on display. It also became clear why, for inexplicable reasons, she and her sister had suddenly felt so unwell in the Louvre that they were forced to leave the museum: no member of Europe’s royal dynasties can remain inside the Louvre for more than half an hour without losing consciousness.

Natalia had always believed her family’s troubles stemmed solely from local criminal elements. However, after thoroughly researching all available online information regarding the discovery and identification of the imperial family’s remains and the proliferation of false Anastasias, she came to a clear realization: all her family’s problems were directly tied to their true origins.

Upon learning of their connection to the Romanov dynasty and the fate of Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova, Natalia and her sister faced a dilemma: either pretend they had never discovered anything and continue living quietly, or attempt to uncover the full truth about Anastasia’s life, prove their Romanov lineage, and thereby protect themselves and their family from being exploited by criminals as biological material for yet another fraudulent scheme aimed at accessing the so-called “tsarist Klondikes.”

After long deliberation, Natalia and her sister decided to pursue proof of their Romanov heritage. They understood that ignorance of their origins had not shielded them over the years from persecution, harassment, or attempts on their lives. They concluded there was only one way to escape relentless pursuit — not only by serious criminal elements but possibly others as well — and that was the public resurrection of their lineage.

Natalia fully realized that if intelligence agencies or criminal groups had been monitoring her and her family for so many years, seeking the truth within her own country or even in Russia would be virtually impossible. She and her sister therefore decided to cautiously discuss the matter with their father, taking care not to traumatize him — he was already 67 years old.

After listening to his daughters, Nikolai Pavlovich told them he remembered almost nothing from his childhood and youth, and that everything he could recall, he had already shared with them earlier. He also warned Natalia that in Moscow, “there’s no one to talk to about this — only bandits.” He added grimly that to change anything in Russia, “you’d have to line up everyone in power against a wall and shoot them.”

Natalia and her sister then resolved to inform their brother and his family, urging them to be extremely cautious when dealing with strangers. Since neither she nor her sister had spoken to their brother or his wife since the closure of the criminal case in 2002—when their brother sided with those who had tried to kill them by deliberately sabotaging the brakes and suspension of their Audi 80—they decided to send him a registered letter to his official residential address.

However, they never got the chance to mail it. Their sister-in-law Yelena unexpectedly came to visit their father about some unrelated matter. Seizing the opportunity, Natalia and her sister decided to tell her what they had learned from Pyotr Vashchenko.

Their sister-in-law’s reaction to the revelation of their Romanov lineage shocked Natalia and Yelena profoundly. Yelena exclaimed, “What — you mean you didn’t know any of this until now? You’re finished now — absolutely finished!” Immediately after these words, she lunged at Natalia. They had to forcibly push her out of the apartment and into the stairwell. During the struggle, Yelena split Natalia’s lip and scratched her face. Natalia and her sister Yelena took a long time to recover from the traumatic encounter.

From Yelena’s words, Natalia realized her sister-in-law had known all along about her husband’s Romanov ancestry — but it remained unclear whether her brother himself was aware of it.

Natalia and her sister decided to write a letter to their brother, as they were no longer certain whether Yelena had been deliberately planted in their family by enemies to monitor and extract information.

Moreover, Natalia learned from an acquaintance named Zhanna — who had been introduced to her by Alla (the same Alla who once brought her a poisoned orange in the hospital) — that her sister-in-law Yelena had previously been married to a Romani man. After she cheated on him, members of his Romani clan attempted to kill her, but she managed to escape. She then joined the Seventh-day Adventist sect, where she met Natalia’s brother. Once she became pregnant, she essentially forced him to marry her — with the help of Natalia’s own mother.

Zhanna told Natalia that Yelena’s marriage to her brother was the only thing that had saved her from Romani vengeance — and that as long as she remained married to him, she would be safe.

Natalia could hardly believe what Zhanna revealed. But when Zhanna saw the wedding photo of Natalia’s brother, she confirmed without doubt that this was indeed the same woman being pursued by local Romani clans. (As it later turned out, Zhanna herself had been married to a Romani man — she was widowed — and had serious ties to the criminal underworld.)

After hearing this, Natalia understood that her brother’s second marriage had been his most fateful mistake. While his first wife, Natalia (coincidentally sharing the same name), had been an honest and decent woman, his second wife, Yelena, was her complete opposite. Moreover, by a strange twist of fate, both of her brother’s wives happened to share the same surnames as Natalia and her sister.

The Vision in the Handcuffs from Yekaterinburg

Natalia recalled that in 2003, another deeply puzzling incident occurred involving her old acquaintance, Yuri Kuzmenkov — a man connected both to Alexander Kovalev and to the story of the search for “the girl with the triple life line on her palm.” After Natalia moved from her grandmother’s neighborhood to live with her parents in another part of the city, she stopped running into Yuri during her dog walks. Nevertheless, he would still call occasionally and persistently invite her over, though she always refused.

In March, her beloved dog Diana died following surgery for bone cancer. Yuri called shortly afterward, and Natalia shared the sad news with him. He then invited her to his place to commemorate her dog. Since Natalia did not drink alcohol — alcohol always made her feel unwell — the only way she could honor her pet was over tea. This was the first time Natalia had visited Yuri’s home. After chatting briefly, he suddenly, as a joke, placed handcuffs on her wrists. These were very unusual handcuffs — unlike modern ones. They were made of a white metal resembling silver and had a flatter, more archaic shape.

In principle, it was a harmless prank. But what Natalia experienced while wearing those handcuffs shocked her so profoundly that she became physically ill. She had long been aware of her ability to “read” information from objects — but what she felt in those moments left her utterly stunned. Suddenly, she couldn’t breathe. Her heart clenched. A storm of emotions surged within her — unbearable pain settled heavily on her soul and pierced her heart. She nearly lost consciousness under the crushing weight of anguish, despair, and suffering — all converging into one overwhelming sensation. Her only desire was to tear herself free from the handcuffs.

Natalia began struggling violently, begging Yuri to remove them immediately. At that moment, however, the cuffs began tightening around her wrists, cutting into her skin. Yuri shouted for her to calm down, terrified by her reaction. He pleaded with her not to move her hands, explaining that these were self-tightening cuffs and could sever her wrists if she struggled further. He grabbed her hands, seeing how distressed she was, and with trembling fingers began fumbling with the locks. For nearly three minutes, he couldn’t unlock them — his own hands shaking from fear. When Yuri finally removed the handcuffs, he brought Natalia water and apologized profusely for the “joke,” clearly shaken by her extreme reaction.

Once Natalia had caught her breath and regained some composure, an intense urge overcame her: she needed to hold the handcuffs again to understand what had just happened. She insisted Yuri let her take them in her hands. He hesitated, afraid of triggering another episode, but eventually relented. The moment Natalia touched the handcuffs again, everything repeated — but this time, she saw the source of the sensations. She distinctly perceived that this was connected to her ancestors, as if the pain were in her blood — as though she herself had once worn these very cuffs and endured this torment. She knew her grandfather Pavel had been imprisoned, and she pictured him — but realized he had worn leg irons, not handcuffs. Someone else had worn these. Natalia concluded the anguish wasn’t tied to her lineage per se, but rather that the handcuffs themselves had absorbed an immense reservoir of negative energy.

Speaking her impressions aloud, she described everything she was sensing — plunging Yuri into shock. She felt the emotions of the person who had been bound in these cuffs and witnessed everything that had happened to them. The victim’s feelings transferred to her with crystal clarity. She saw, as if through the victim’s eyes, how approximately ten people were murdered before him — not merely killed, but savagely tortured: hacked to pieces, doused with acid, subjected to unimaginable torment. The sheer agony, despair, and helplessness in the face of such monstrous cruelty flooded her consciousness.

After the torture, the victims — already barely alive — were finished off with bayonets. In truth, there was little left to kill; their bodies were reduced to mere semblances of human form. The person in the handcuffs was being interrogated, clearly because his captors knew he possessed vital information. Yet he refused to speak — nor did any of the ten others. They all died guarding their secret. Each victim was executed one by one, in full view of the next. The moral torment endured by the bound witness was beyond words. Finally, he too was tortured — but his tormentors never obtained what they sought. Overwhelmed, Natalia cried out to God — she had never witnessed such barbarity in her life. Yet one thought rang like an alarm in her soul: This is directly connected to my ancestors. Trembling uncontrollably, she spoke everything aloud. Then, in horror, she flung the handcuffs away and screamed at Yuri to throw them out immediately — insisting they were saturated with horrific energy and must not be kept in the house. She demanded he dispose of them at once.

Yuri, deeply disturbed by Natalia’s words and behavior, also felt unwell but promised to get rid of them. Natalia then asked where he had obtained the handcuffs. He replied that a police officer friend had given them to him, explaining they were antique — dating back to Imperial Russia — and that such cuffs were reserved exclusively for nobles and princes. They featured a special self-tightening mechanism and had been used for torture. Only after World War II were they universally banned worldwide. Yuri spent a long time calming Natalia down — she was as pale as a corpse.

At the time, Natalia believed Yuri was simply a television repair technician. She later learned he was originally from Yekaterinburg and had moved to Gomel only in the early 1980s. His grandfather had been a veteran of the NKVD. Natalia then assumed the handcuffs had likely been inherited from his grandfather. In early 2005, Natalia’s acquaintance Zhanna — the same woman who had earlier revealed details about her sister-in-law Yelena’s first marriage to a Romani man — informed her that Yuri was, in fact, a known criminal authority widely referred to as “Kuzma.”

After confirming her own Romanov lineage, Natalia came to a chilling realization: these handcuffs could very well have come from the Ipatiev House — and it was in these very cuffs that her ancestors, the Romanov imperial family, had been so brutally tortured. All these memories solidified Natalia’s conviction that powerful criminal forces had been closely monitoring her family for a very long time. She and her sister resolved to seek out individuals who might help them — not in Russia, perhaps, but at least abroad. At the time, the only accessible means was the global internet. Natalia understood that regular letters might never reach their destination, but emails and direct appeals to those genuinely interested in the Romanov case stood a better chance.

She sent registered letters with return receipts to monarchist organizations and to individuals actively investigating the murder of the imperial family and the theory that one of the daughters had survived. Sadly, she received no replies — not even acknowledgment that the letters had arrived. The letters simply vanished, never reaching their intended recipients.

Strange Incidents in Sherstin

While Natalia and her sister were trying to reach anyone who might help resolve the question of their possible kinship with the Romanov dynasty, several more inexplicable events occurred in Natalia’s life.

In the spring of 2005, just before Easter, Natalia and her sister traveled with their father to the village of Sherstin to tend to their relatives’ graves — painting fences and cleaning the burial sites. They arrived at the cemetery after 6 p.m. and immediately began repainting the fence around the graves of their grandmothers, Pelageya and Irina. So engrossed were they in their work that they didn’t notice more than two hours had passed. Around 8:30 p.m., two unfamiliar men approached the grave. One appeared to be about 60 years old; the other was roughly 40–45. Their clothing looked oddly outdated — not at all contemporary. They were examining the graves as if searching for a specific one.

Natalia asked them,

— Whom are you looking for?

One of the men replied,

— We’re looking for Volkov’s grave.

Natalia asked,

— When did he die?

The younger man answered,

— He died in 1985.

Natalia responded that neither she nor her sister knew anyone by that name and suggested they ask their father, who might be able to help. At that moment, however, Natalia’s father had wandered off toward the river, some distance from the cemetery. Her sister Yelena advised the men to search in that row of graves, since Grandmother Pelageya had died in 1983.

The men then asked Natalia and her sister,

— And who are you descended from?

The older man added,

— What’s your father’s name?

Natalia replied,

— Nikolai Pavlovich.

Upon hearing this, both men exchanged a startled glance and stood frozen in place for several minutes. Then, without a word, they walked away. Suddenly, the younger man turned back toward Natalia and her sister, began making the sign of the cross from a distance, bowing repeatedly and whispering, “Holy, holy, holy, holy, holy, holy…”

Their strange behavior reminded Natalia that they were alone at the cemetery, nearly at 9 p.m. She quickly gathered their belongings to leave. Her sister Yelena went to find their father. On the way home, Yelena asked their father whether he knew anyone named Volkov — the man whose grave the two strangers had been seeking. Her father replied that no one by that surname had lived in his village during his time.

Later, during Radonitsa — a traditional day for visiting graves — Natalia, her sister, parents, and mother returned to Sherstin and stopped by the only surviving distant relatives in the village from the Khazanov line. Natalia recounted the strange cemetery encounter and asked if they knew anything about Volkov. To her surprise, none of them had ever heard of such a surname in the village — it had never existed there at all.

Later, Natalia searched online for the name “Volkov” and discovered that Empress Alexandra Feodorovna had had a personal valet named Volkov. After this revelation, Natalia was no longer certain whether she and her sister had actually seen living, real people at the cemetery at sunset — or whether they had encountered ghosts or angels in human form.

The consequences of going online for the first time

In 2005, Natalia created her first account on the social networking site Odnoklassniki (“Classmates”). She found many former classmates who had scattered across various cities and countries. However, within a couple of weeks, unknown individuals began appearing on her profile, posting accusations that Natalia had once pushed a pregnant woman, allegedly committing a crime. They also accused her of using other people’s photographs on her page, calling her a “hideous creature with Gypsy features.” Eventually, a scrolling banner appeared on her profile with the message: “Don’t communicate with this monster — she’s utterly vile.” Seeing this, Natalia tried to remove the banner, but realized it was either a hacker attack or a virus. Many of her classmates wrote to her in confusion, asking what was happening on her page. Friends also complained that someone was sending them offensive messages from her account. Forced to act, Natalia temporarily deleted her Odnoklassniki profile, informing all her classmates and friends of the situation. To her astonishment, however, duplicate profiles mimicking hers — with identical content — soon appeared on the site. Natalia couldn’t understand what was happening or who would go to such lengths. Was this a prank, or a deliberate campaign by malicious individuals?

Several months later, Natalia reactivated her profile — only to be immediately targeted again by strangers repeating the same accusations and insults, attacking her human and feminine dignity. She was even urged to contact “politician Zhirinovsky” in private messages. Although Natalia had no desire to engage with these aggressive strangers, she decided to clarify the exact nature of the accusations and their basis. Several people messaged her privately, persistently accusing her of a crime and issuing threats. They again claimed she was using stolen photos and lamented, “They keep trying to kill her, but she’s so resilient — she just won’t die.” They also repeatedly complained that Natalia “still hadn’t given birth to a child.”

At first, Natalia dismissed these threats and accusations as the actions of mentally unstable individuals. But after a while, her harassers began citing specific facts from her personal life — details no stranger could possibly know. Natalia began to suspect this was the work of local criminal elements involved in the earlier search for “the girl with the triple life line.”

Meanwhile, Natalia urgently needed to address the question of proving Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova’s survival. After long deliberation, she resolved to publicly declare her Romanov lineage online. In early 2006, she launched a website containing information about Anastasia Romanova’s life and stated that her family was being persecuted by criminal organizations. She appealed for help in gathering evidence of Anastasia’s survival, hoping to attract attention from people abroad. Instead of support, however, she received only insults, threats, and humiliation. The only respite came on her Odnoklassniki page — where, for two weeks, an eerie silence reigned.

Examination of Materials from the Criminal Investigation into the Murder of the Imperial Family and Identification of Their Remains, as well as Materials Related to the Identification of Impostors Claiming to Be Anastasia Romanova

Natalia herself did not devote much attention to studying the materials concerning the investigation into the murder of the imperial family or the numerous claims by false Anastasias. These matters were meticulously researched by her sister Elena, who had been nicknamed “the quartermaster” in childhood and “the office rat” in her youth — despite serious vision problems.

While examining the materials related to the identification of Natalia Bilikhodze as Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova, Elena discovered many intriguing details. Of particular interest were genetically inherited traits related to the development of the musculoskeletal system that had been documented in Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova. The most significant evidence was contained in forensic expert reports from 1996–2000.

The identification of N. P. Bilikhodze and Anna Anderson as Anastasia Romanova was based primarily on two distinctive features of skeletal development: a rare congenital foot pathology and handwriting analysis.

1. Presence of an Extremely Rare Congenital Foot Pathology

During civil litigation proceedings (beginning in 1922), both Anna Anderson and Anastasia Romanova were found to exhibit hallux valgus — a deformity in which the metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe is misaligned, causing the toe to angle inward and distorting the other toes. This condition may be either congenital or acquired. Contributing factors include poorly fitted footwear, which can lead to osteoarthritis of the big toe joint. Similar foot deformities may also result from conditions such as degenerative osteoarthritis or osteoporosis.

In contrast, in 1995, specialists from the Otari Gudushauri National Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics (Ministry of Health of Georgia) — N. N. Kacharava, M. V. Sakvaralidze, and G. K. Gogichadze — identified a different anomaly in both Natalia Bilikhodze and Anastasia Romanova (based on video and photographic materials): bilateral pes excavatus (hollow foot), the opposite of flatfoot.

Diagnosis of pes excavatus is typically performed using plantography — a method involving analysis of footprints left on paper. Radiography of the feet is another diagnostic tool. Additionally, to determine the underlying cause of hollow foot, further examinations may be required, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord and a comprehensive neurological evaluation to assess the state of the nervous system.

In individuals with pes excavatus, the foot’s supportive, balancing, and shock-absorbing functions are impaired. This condition may be either congenital or acquired. Causes include improperly healed fractures of the calcaneus or talus bones, burns, neuromuscular disorders — and in 20% of cases, the cause remains unknown.

(Sources on the identification of N. P. Bilikhodze:

http://lebed.com/2002/art2985.htm,

http://www.x-libri.ru/elib/smi__661/00000002.htm)

This finding particularly intrigued Natalia, as she herself had a congenital bilateral pes excavatus. In 1999, orthopedic specialists at the Institute of Traumatology and Orthopedics informed her that this very anomaly was the root cause of her spinal problems. Like Natalia Bilikhodze, Natalia was also diagnosed with cauda equina dysplasia — a congenital narrowing of the spinal canal. This is an exceptionally rare spinal condition, directly responsible for her mobility and posture issues.

Since childhood, Natalia’s sister and friends could always recognize her footprints on the beach — only the toes and heel left impressions, with no trace of the lateral arch. Natalia never wore custom orthopedic footwear (doctors never recommended it), but she consistently wore high heels, as they provided her greater comfort.

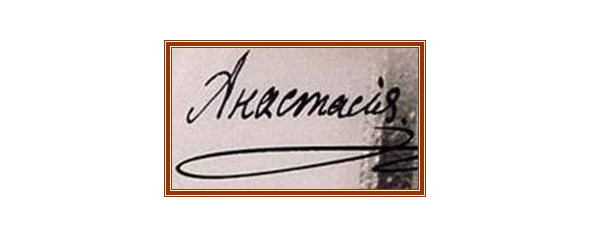

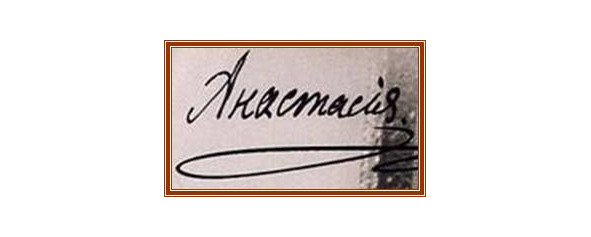

2. Handwriting Analysis

Another crucial piece of evidence used to establish the purported identity of the impostors as Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova was the similarity between their handwriting and hers. However, handwriting analysis presents significant challenges, as handwriting has a complex psychological and physiological basis and is influenced by numerous internal and external factors.

Distorting influences during writing — such as threats, unnatural body posture, stress, alcohol intoxication, age-related changes, imitation of printed type or another person’s handwriting or signature, or even deliberate self-forgery — can all alter handwriting characteristics. Additionally, illnesses affecting the eyes, hands, or the nervous and mental systems over a 10–15 year period may also significantly modify handwriting features. Furthermore, forensic handwriting examination based solely on photocopies of documents is permissible only in exceptional circumstances.

Comparative handwriting analyses of Anna Anderson and Natalia Bilikhodze against known samples of Anastasia Romanova’s handwriting were conducted using just two photographs: one provided during the promotion of Anna Anderson (1922–1970) and another during the campaign supporting Natalia Bilikhodze (1995–2002).

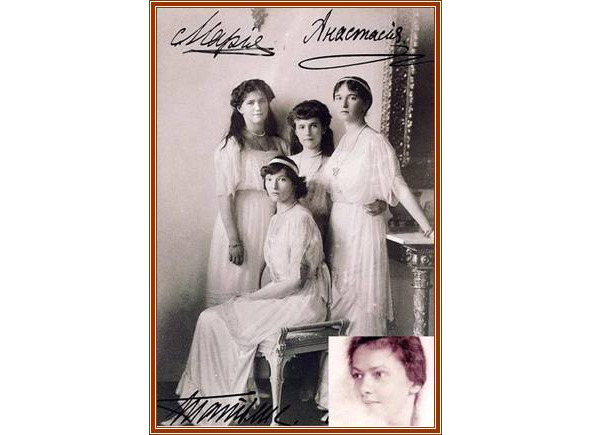

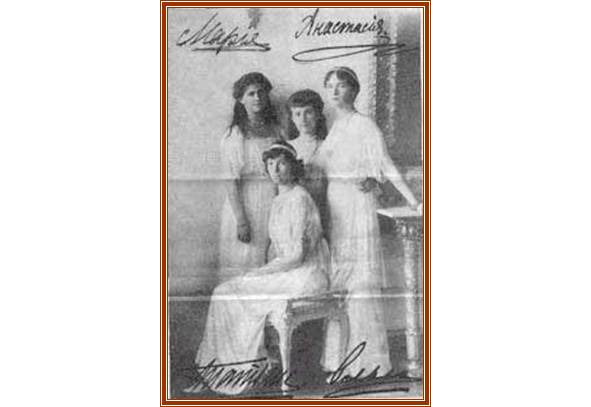

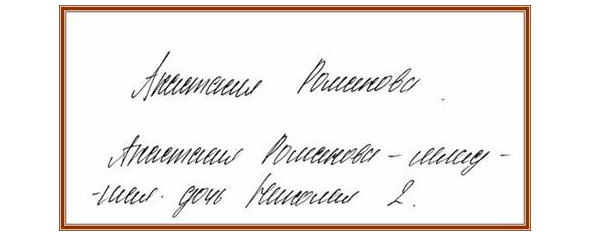

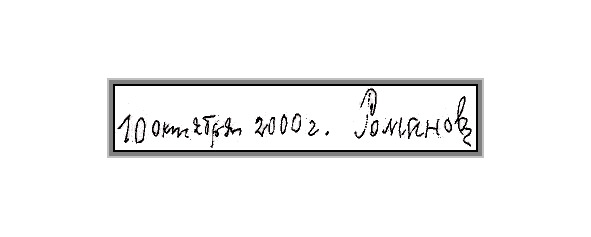

Photograph featuring handwriting samples of the daughters of Emperor Nicholas II (Olga, Anastasia, Tatiana, and Maria). The photographs were used during the promotion of the impostors Anna Anderson (1922–1984, left) and Natalya Bilikhodze (1995–2000)

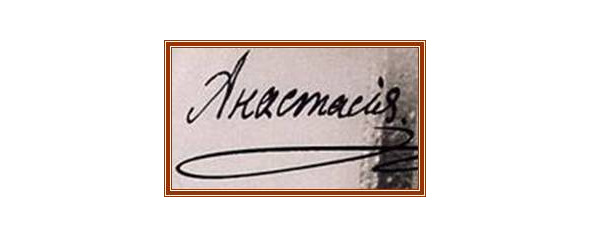

Handwriting samples of Anastasia Romanova and Anna Anderson (Chaykovskaya

Handwriting samples of Anastasia Romanova and Natalia Petrovna Bilikhodze

Handwriting samples of Anastasia Romanova and daughter of Nikolai Pavlovich.

Natalia and her sister noticed that the only difference between the two photographs was their physical condition: the photograph used in the case of N. P. Bilikhodze appeared more worn and had two distinct creases. Even the ink blot (photo damage) at the top, above the underline beneath Grand Duchess Maria’s signature, was identical in both images.

As evident from the handwriting samples of the impostors, one can conclude only an approximate similarity between the handwriting of Anna Anderson and that of Anastasia Romanova. In contrast, the handwriting of N. P. Bilikhodze showed no resemblance whatsoever to Anastasia Romanova’s.

Natalia could not understand one thing: how could experts in civil litigation proceedings have concluded that the two handwritings were identical? There seemed to be only one plausible explanation — if, for the forensic examination, a handwriting sample from another individual had been submitted, one whose handwriting was nearly 100% identical to that of Anastasia Romanova.

To Natalia’s sister Yelena’s great astonishment, she discovered that her own handwriting was visually almost indistinguishable from that of Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova in the photographs presented for expert analysis. At first, she could not comprehend how this was possible. However, after carefully studying the materials on handwriting identification, she learned that a grandmother’s handwriting can indeed be nearly identical to her granddaughter’s, as genetic inheritance influences the structure of the eyes, the hand, and the nervous system — all of which directly affect handwriting formation.

It also struck Natalia and her sister as strange that the experts in 1922 had identified bony calluses (hallux valgus) in Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova but had not detected another pathology — bilateral pes excavatus (hollow feet). Conversely, the specialists from the Georgian Research Institute of Orthopedics and Traumatology in 1995 identified bilateral pes excavatus in Anastasia Romanova but failed to notice the hallux valgus deformity.

Moreover, the evidence presented to identify the impostors as Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova was not only dubious but also internally contradictory.

Nevertheless, for over forty years, Anna Anderson attempted — through civil courts in Germany and England — to prove she was the surviving daughter of Emperor Nicholas II. She was unsuccessful. She died in 1984. Renowned geneticists Peter Gill (in the 1990s) and Michael Coble (in 2010) conducted analyses of Anna Anderson’s biological tissues and hair. Genetic testing conclusively disproved any kinship between Anna Anderson and either the British royal family or the Romanov imperial dynasty.

The false Anastasia, Natalia Bilikhodze, asserted her Romanov lineage from 1996 to 2000. In 2000, the Interregional Public Charitable Christian Foundation of Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova was registered, along with several overseas branches (in Belarus, Western Europe, the Middle East, and Canada). In September 2000, the foundation submitted documents to the Office of the State Duma claiming that the youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, Anastasia, was alive and living under the name Natalia Petrovna Bilikhodze in the Moscow region. They also provided materials from the Tbilisi court proceedings, including 22 court-commissioned forensic examinations conducted in Russia, Georgia, and Latvia to identify N. Bilikhodze as A. Romanova.

In December 2000, N. P. Bilikhodze died at the Central Clinical Hospital in Moscow — a fact reported in Rossiyskaya Gazeta on July 8, 2002. Molecular genetic testing of biological samples from the deceased citizen Bilikhodze was carried out at the Russian Center of Forensic Medical Expertise under the Ministry of Health of Russia. Initiated by the same working group, the analysis began on December 18, 2000, and concluded on January 12, 2001. It was conducted by Dr. Pavel Leonidovich Ivanov, Doctor of Biological Sciences. The DNA results definitively refuted any familial link between N. P. Bilikhodze and either the British royal family or the Romanov dynasty.

All the discovered facts — the shared foot and spinal anomalies with Anastasia Romanova, and the nearly 100% handwriting match between her sister and the Grand Duchess — filled Natalia with vague feelings of anxiety and melancholy. She recalled several other deeply strange events from past years that she had never been able to understand or explain.

As soon as Natalia began researching the phenomenon of false Anastasias, she came across a news article on one website stating that N. P. Bilikhodze’s mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) — inherited through the maternal line — perfectly matched that of the lineage of Queen Victoria of England. However, experts later found traces of a potent poison in the blood of the 100-year-old “grandmother” Bilikhodze — poison that would have been lethal to an elderly person of that age. Additionally, her blood contained a full profile of female sex hormones typical of a woman in her prime reproductive years — hormones that could not possibly be present in a woman over 70. This triggered a major diplomatic scandal — Great Britain nearly severed all relations with the Russian Federation. Strangely, it was also at the end of that same year that Boris Yeltsin announced his resignation from the presidency of the Russian Federation. However, within a few months, the article was removed from the website, and Natalia was unable to save or preserve it.

Natalia also recalled a very strange incident that occurred to her in Minsk in the autumn of 1999. At the time, she was undergoing medical examinations to determine the cause of her severe health conditions. She had just begun to suspect that her acquaintance Alla had brought her a poisoned orange while she was in the hospital. Since the local polyclinic refused to allow her to take additional tests, Natalia decided to have the analyses done at the polyclinic registered to her sister Yelena’s address. Yelena went to the clinic, obtained a referral in her own name, but Natalia gave blood under Yelena’s name instead. Later, Natalia and her sister Yelena traveled to Minsk to visit the Endocrinology Dispensary to take paid hormone tests, as such tests were unavailable in their hometown. After providing the blood sample, Natalia was told the results would be ready in three weeks. However, after only two weeks, she received a call saying there wasn’t enough blood for several hormone tests and that she needed to come back to provide an additional sample. As an experienced nurse, Natalia found this behavior by the medical staff highly unusual. Coincidentally, she and her sister needed to deliver their course papers to an institute in Minsk around that time, so they decided to go.

At the dispensary, they drew 20 cubic centimeters of blood from Natalia (whereas only 10 had been taken the first time). They also asked her to sign some documents related to the blood tests, explaining that, since it was a paid service, written confirmations were required for the tax authorities. Yet during her first visit, she hadn’t been asked to sign anything. But the oddities didn’t end there. Natalia and her sister waited nearly three hours for some of the test results to be issued. During that time, the senior nurse, then the deputy chief physician, and finally the chief physician of the Endocrinology Dispensary each separately urged Yelena — Natalia’s sister — to provide a blood sample for “any test,” offering it completely free of charge. Yelena flatly refused to give any blood. This conduct by the medical personnel was not merely strange — it was deeply suspicious.

At the time, Natalia wondered whether traces of toxic substances (poisons) might have been accidentally detected in her blood. But after studying the materials related to the promotion of N. P. Bilikhodze as Anastasia Romanova, Natalia gained strong grounds to suspect that her blood might have been used by fraudsters to falsely identify N. P. Bilikhodze as Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova.

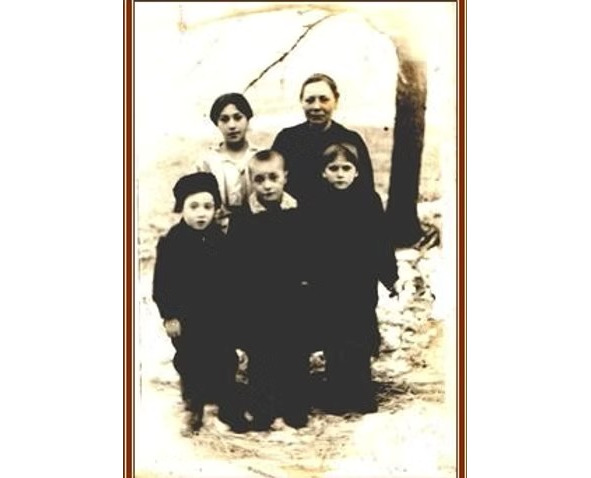

Her suspicions intensified further after her only meeting with her brother following his receipt of Natalia’s registered letter informing him of their Romanov lineage. Her brother Alexander brought a photograph from the family album (he had taken many family photos when he first got married). It was an old photo from 1943–44 showing their father, presumably with his older brother Pyotr and sister Alexandra. Standing next to them was presumably their mother — Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanova. (The word “presumably” is used here because there is no confirmed, verified evidence.)

Natalia’s father said he didn’t remember who exactly he had been photographed with, as he appeared to be no older than three or four years old in the picture. However, in this photo, standing beside him was a young woman aged 17–20 with distinct Caucasian features who bore a striking resemblance to Natalia Petrovna Bilikhodze — both in facial appearance and in the presence of torticollis (a tilted neck), visible both in the unknown girl in the photo and in N. P. Bilikhodze’s elderly photographs. Another strange fact was that N. P. Bilikhodze had no photographs dated after 1917; only photos from 1996–2000 were submitted to the courts — at a time when Grand Duchess Anastasia would have been over 95 years old. However, if the girl in the family album photo was indeed Natalia Bilikhodze, then by 1996–2000 she would have been only 72–76 years old.

Photos from a family album dated 1943–44 and a photograph featuring an unknown man and woman (allegedly Anastasia Romanov).

Comparison of photos from the girl’s family album with Natalia Bilikhodze (the false Anastasia Romanova). There is a noticeable facial resemblance and a right-sided torticollis (head tilted to the right).

Her brother refused to give Natalia the photograph, so that same day she took a picture of it and made a copy. Natalia told him she was planning to conduct DNA testing. Her brother flatly refused to take a DNA test. He behaved very arrogantly and hinted that if Natalia and her sister tried to make any decisions behind his back, a fire might “accidentally” break out in his apartment — destroying the photograph.

Natalia understood that her brother might possess other evidence regarding Anastasia Romanova’s survival, but neither she nor her sister were in a position to forcibly obtain it. He lived separately, and Natalia was not welcome in his home. Their parents, too, had distanced themselves from him after the criminal case involving the car sabotage; only their mother occasionally spoke with him on the phone or met with his wife.

Searching more thoroughly through old photo albums for additional wartime photographs, Natalia found another picture. On the back, it was inscribed: “This is A.” She couldn’t be certain who was depicted in the photo, but upon comparing it with childhood photographs of Anastasia Romanova, she noticed a strong resemblance. Judging by the condition of the photographic paper and the woman’s apparent age, the photograph appeared to be pre-war.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.