Бесплатный фрагмент - The Silent Mountains

A Novella and stories

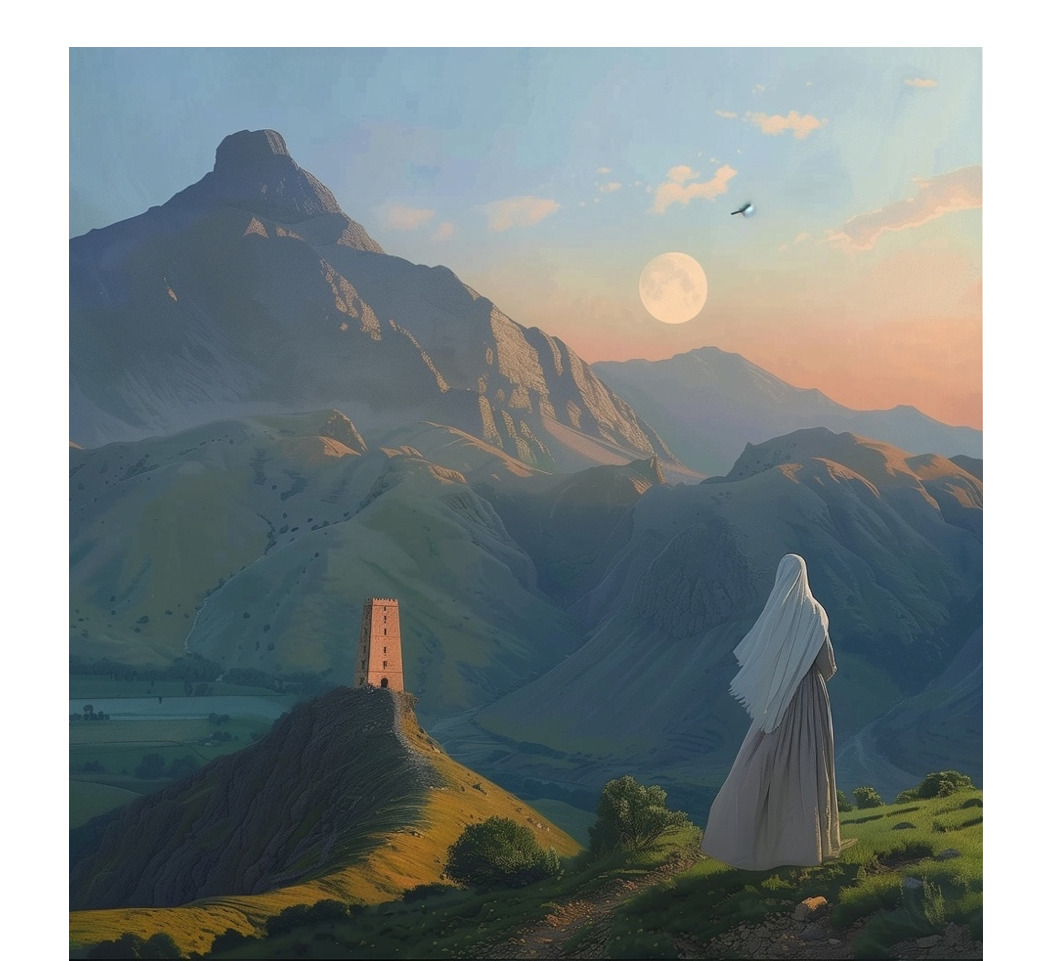

Dedicated to the Children of War and the Chechen Nation!

⠀

⠀

The mountains will never forget; for centuries,

they will mourn in silence the darkest days

of our people.

⠀

⠀

Maryam Nashkhoeva

translator, and English language teacher. She holds

a PhD in Philology and is a faculty member

at Lomonosov Moscow State University.

She is also the author of numerous

linguistic studies and an active public figure.

About the author

Maryam Nashkhoeva is a member of the Writers’ Union of Russia, the International Writers’ Guild, the Women’s Union of Russia, NATE — the National Association of English Teachers, an Ambassador of the Eurasian Creative Guild (ECG) in London, and the author of the book «In the Shade of Sidrat».

She was nominated for the All-Russian National Literary Prize Writer of the Year — 2017 in the «Debut» category for her story «Sing Me a Lullaby, Daddy!». She also received nominations for the Heritage — 2017 literary award for «The Smell of Happiness», the Writer of the Year — 2019 prize for «In the Shade of Sidrat», the Writer of the Year — 2020 award (Debut category) for «Dazzling Mind», and the Writer of the Year — 2021 (Debut category) for her short story «The Locket».

Her work has been featured in several literary collections, including Catalogue of MMKVA–2021, RSP. Prose 2021, and Anthology of Russian Prose 2022. Her short story «The Smell of Happiness» was also included in the youth literary anthology «Debut — Constellation of Words and Colours», published in 2020 to showcase young writers and artists of the Chechen Republic.

Maryam Nashkhoeva’s contribution to Russian literature has been recognized with commemorative medals honouring Nobel laureate Ivan Bunin (Ivan Bunin — 150 Years), Fyodor Dostoevsky (Fyodor Dostoevsky — 200 Years), and Anna Akhmatova (Anna Akhmatova — 130 Years). These public awards were presented by the President of the Russian Union of Writers, D. V. Kravchuk.

She was also awarded the Medal of the Women’s Union of Russia during the presentation of her book «In the Shade of Sidrat» at the House of Nationalities in Moscow. This medal is given to exceptional women for their creative and professional achievements.

The books «In the Shade of Sidrat» and «The Silent Mountains» have been translated into English by Maryam Nashkhoeva and are available on English-language online platforms in the UK, Europe, and the USA. Maryam Razambekovna also translated the historical poem about the first Imam of the North Caucasus «Sheikh Mansur» into English.

Those who are gone will never return, but their souls will yearn for their homeland even after death.

⠀

⠀

Maryam Nashkhoeva

This novella «The Silent Mountains» is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Chechen and Ingush deportation.

⠀

⠀

Based on my family’s stories.

The Silent Mountains

The mountains will never forget. For centuries, they will mourn in silence the darkest days of our people. The heart will never forsake the memory of those who perished from cold and hunger — children, women, and the elderly — abandoned in the vast, unforgiving steppes of Kazakhstan.

The deep, gaping wounds carved into the lives of our people during those dreadful days of deportation will never fully heal. Those who are gone will never return, but their souls will yearn for their homeland even after death.

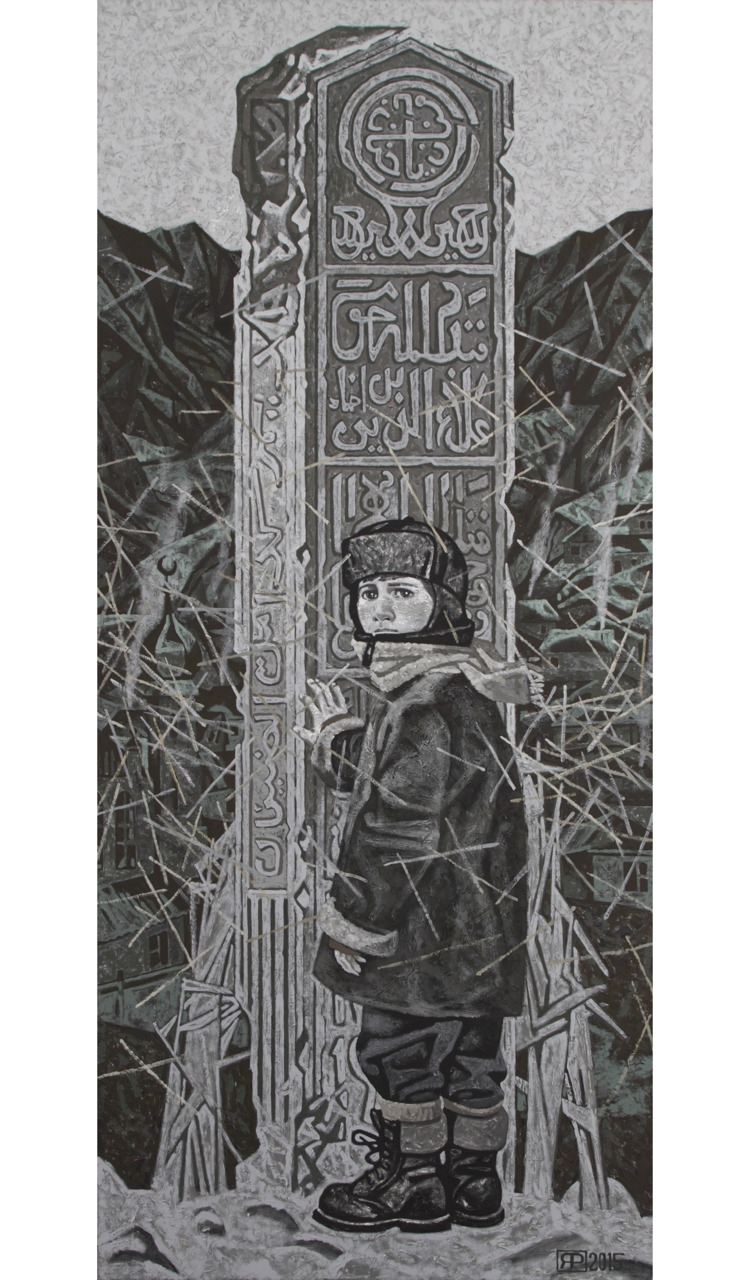

Every year on February 23rd, I close my eyes and try to walk the thin thread of the past like a blade back to 1944, when the Chechen and Ingush people were exiled. I attempt, feebly, to feel the horror that befell our people. What did they truly endure when they were given only ten minutes to gather the possessions of a lifetime? When told to take only what was most valuable, what could be more valuable than life itself, or the land you call home?

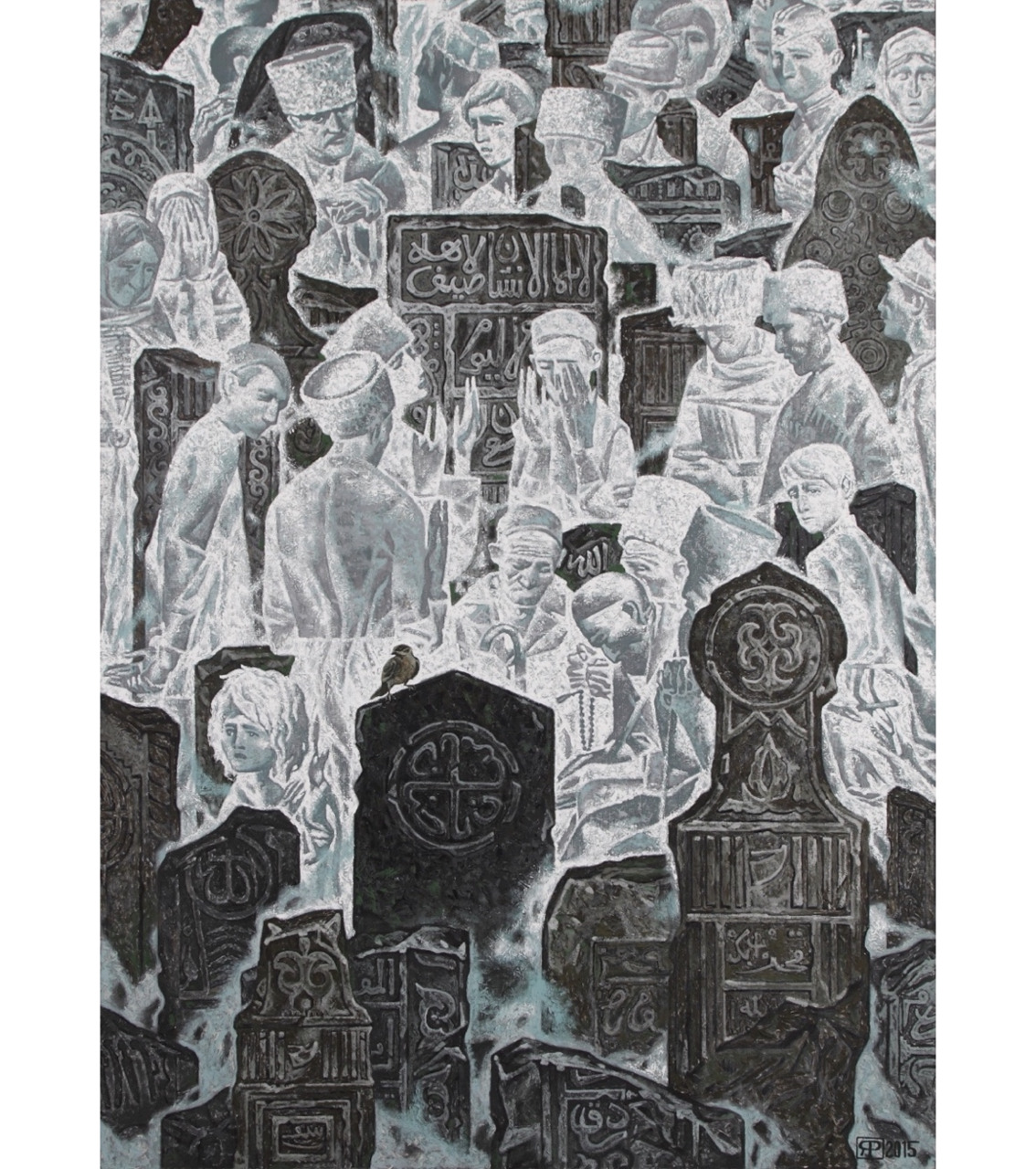

A person cannot live without a homeland, just as they cannot live without a heart. Exile is no different from death. Every exiled Chechen or Ingush carries within them a vast cemetery, buried deep in their heart, where all their loved ones lie.

On February 23, 1944, our people were condemned to years of fatal separation from their homeland. They were herded into freight wagons and deported to alien, frozen steppes. They died from cold, from hunger, from disease. In a single day, an entire nation was stripped of everything: family, home, belongings, archives, and sacred relics. Even those who had bravely defended the country paid this cruel price for their courage, for their loyalty, for their patriotism.

A whole generation was raised on stories of deportation ours included. Grandparents would speak with tears in their eyes, their voices cracking from the weight of memory. Perhaps we could never have truly understood their pain had we not walked through our own war, bearing the scorched imprint of living memory that sears the soul with the fire of unending loss. No matter how often those dark events are retold, every story tears the heart anew:

«When we were deported, I was only nine. But not a day in my life has passed when I didn’t remember those horrors. For years, I had nightmares: the screams of children, the weeping of women, the silent tears of men. I still smell the train cars, the scent of death. The stench of the corpses people tried to hide, hoping the guards wouldn’t throw them out into the snow… but nearly no one succeeded.

I remember an old man with a white beard. He stepped off the train at a station out of necessity and the train began to move. He didn’t make it back. I remember him shouting after us, begging not to be left behind. He chased the train, stumbling in the snow, falling, rising, waving his arms desperately. There was such despair in his eyes. And then he became a silhouette, growing smaller and smaller, until he vanished into the mist.

Decades have passed, but I still dream of that old man. He waves to me, asks me to stop the train, to help him climb in. But I can’t. And I always wake up crying.

I remember little Muhammad, just two months old. He was in our wagon with his mother. He died on the second day from cold and hunger. She held him for several more days as if he were still alive, hoping to bury him properly, with a prayer. But she never got the chance. The guards threw his tiny body into the snow at the next station, just like so many others. Entire families died altogether in those black days.

I remember a young woman’s crying from the next car… so loud at first and quieter with each day. Then it stopped completely. Her heart had broken. She hadn’t even been allowed to hold her baby one last time. And that grief killed her.

Even now, after so many years, it’s hard to speak of these things. Words catch in the throat. They feel like moments frozen in time, suspended in a web of pain. But somehow, I feel lighter when I speak of them. My endless sorrow quiets slightly.

I try to picture my family: my parents, my brothers and sisters alive and well. Their smiles, their laughter, warm embraces, kind words. After all, a person holds much more than just six letters making up the noun. We are filled with memories: thoughts, feelings, love, and loss. Our lives are made of tears, of grief and joy and when they dry, only the memories remain.

In 1944, my father was on the front, defending our homeland. At the time, young soldiers were stationed with us, supposedly to familiarize themselves with the area. My mother gave them a small house in our yard with two rooms. She shared what little we had with them, saying they were still so young, and that it was our duty to care for them as guests in a foreign place.

A few days before the deportation, one of those soldiers Yevgeny, who called my mom «Mother», warned her.

While she was making lunch, he knocked quietly and asked to speak. I stood behind the door, listening. I knew a little Russian.

— Mother, — he said nervously, — you’ve always been kind to us. You’ve shared your last piece of bread with us. I need to tell you something, but if anyone finds out, we’re all in danger. Please… don’t tell anyone.

— What’s wrong? — my mom asked.

— You’re being deported tomorrow.

— Deported? Why? — she asked, tears welling in her eyes.

— Don’t ask me. I don’t know. We were sent here to prepare you quietly for the journey.

— But my husband is fighting at the front. So is my only brother! They’re risking their lives for the country!

— If it were up to me… Forgive me, Mother. I just wanted you to know. If I die at the front, I want my conscience to be clean.

— What will happen to us? The children are still so small. Where will they take us?

— Somewhere cold. I’ll help you pack… I want to thank you for your kindness.

— Son… is this really happening?

— You always told us everything is in the hands of the Almighty. You taught us that. — And with that, he left.

My mother cried. I ran and hid under the bed; afraid he would discover I’d heard. Later, I crawled out and hugged her.

— Selima, — she said, — everything will be alright. Don’t worry.

— But Mommy… where will we go? This is our home.

— I don’t know. But if anything happens to me, promise me — you’ll protect your brothers and sisters.

— But Mommy… how can we leave our home? Maybe this is all just a mistake?

— Selima, I want to believe that too. I want to believe this isn’t real.

— What about Daddy and Uncle? They’ll come back from the front, and we’ll be gone.

— They’ll find us, wherever we are. Don’t worry.

— I don’t want to go. I want to stay in our home.

— Listen to me, Selima. The Caucasus will always be in our hearts. The Almighty is with us, wherever we go and so is our boundless faith. You must always remember that.

— Yes, Mommy, I will.

— We are from Chechnya. We are Chechens of the Dishni clan. Honor your traditions. Know who you are and where you come from. Show respect to everyone, no matter their nationality, that is the command of the Almighty. Don’t let hatred take root in your heart. Spread kindness and mutual respect. That is what will make you worthy of your ancestors, of your homeland, of the Caucasus.

— I’ll remember, Mommy. I won’t let you down.

— You’ve always been a smart girl. Take care of your brothers and sisters. Be their rock, be the fortress no one can tear down.

— I will, Mommy. Be certain. I promise.

— And one day… we’ll come home again.

She hugged me tightly, and I cried.

Through the window, we saw Uncle Zhenya quietly gathering food and warm things in a sack cornmeal, some dried meat, a blanket, and a padded jacket. When he finished, he came to the window and said:

— Mother, I’ve done what I could. I packed food and clothes for the road. Please forgive me. I’ll come at dawn. Dress the children warmly. It might save you from the cold.

— Thank you, — Mommy whispered.

There were four of us. I was the eldest. Arbi was seven, Khutmat was four, and Kharon was only two. That night felt endless. We packed what we could. Mommy dressed the little ones in layers, then sat in prayer until dawn, turning her beads, whispering to the Almighty.

At daybreak, our neighbour Zabu ran into the yard, her eyes red with tears.

— Asma, did you hear? They’re deporting us!

— How do you know?

— Polina, the nurse, told me. She said to get ready, but she doesn’t know when it’s happening.

— It’s true. I found out last night.

— Oh God. When?

— Today.

— May the Almighty help us!

— Zabu, listen to me. Go home now. Dress your son warmly. Pack as much food as you can.

— We’ll get through this. We must stay strong.

— Hurry up, there’s no time left. Go out through the garden, if anyone sees you, it might cause trouble.

Just after Zabu left, there came a knock on the door. Mommy stepped out and saw the soldiers. Uncle Zhenya was among them.

— Pack your things. You’re being deported, — one of them said, coldly. — You have ten minutes.

Mommy didn’t speak. She woke the children, and we dressed.

That day became our people’s «kyemat-de» — our day of reckoning. The people were told to take only the barest essentials. Homes filled with panic. Outside, women cried. Babies wailed. We were herded onto trucks and taken to the station. No one knew where we were going. Women sobbed; men clenched their jaws to hold back tears. Then one of them called out:

— Everything is by the will of the Almighty! Wherever they take us, He will be with us! Submit with dignity! Never show them your tears!

After that, the crowd fell silent. Hours later, at the train station, we were crammed into freight cars… several families to each one. We left our homeland behind for what would be thirteen years… or forever. Even those who had fought for our country were deported. No one was spared.

There were no conditions in the wagons. People died at nearly every stop from hunger, from cold, from typhus. Their bodies, unburied, were left in the snow.

In our car, there were mostly children. I still see Muhammad’s snow-white hands. I still see the guard tearing his lifeless body from his mother’s arms and throwing it into the white snow at the next stop.

Zabu lost her mind from grief. She called out for her child, for her husband. The next day, she passed away too. Mommy tried to hide her body, but she couldn’t.

Throughout that hellish journey, we were too afraid to even speak, terrified that we too might be thrown into the snow like Zabu and little Muhammad.

The most terrifying moments came when the train cars stopped, because we knew what it meant: they were unloading the dead. There would be no proper burials.

The bodies would be discarded and forgotten in the cold, endless steppes.

But we were incredibly lucky. No one in our family died. Neither fully alive, nor yet dead, we somehow reached the unknown destination.

I remember it was early March when the train finally stopped. We were dropped off into an empty, snow-covered field. It was bitterly cold. Then, one by one, we were loaded onto sleds and taken somewhere no one knew where, or where we would live.

I held Kharon in my arms. He wasn’t crying only once did he quietly whisper, «water,» asking for a drink. His little hands were like ice. His cheeks were red, which meant he was still alive. Mommy scooped up some snow, melted it in her hands, and wiped his face and lips with the water. He stayed quiet, and from time to time, I checked to see if he was still breathing. Then I touched his forehead, it was burning with fever. I didn’t tell Mommy… I was too afraid of worrying her more. I remember the bodies behind us, hidden beneath a blanket of snow white and soft, as if trying to shelter them from the cruelty of this world.

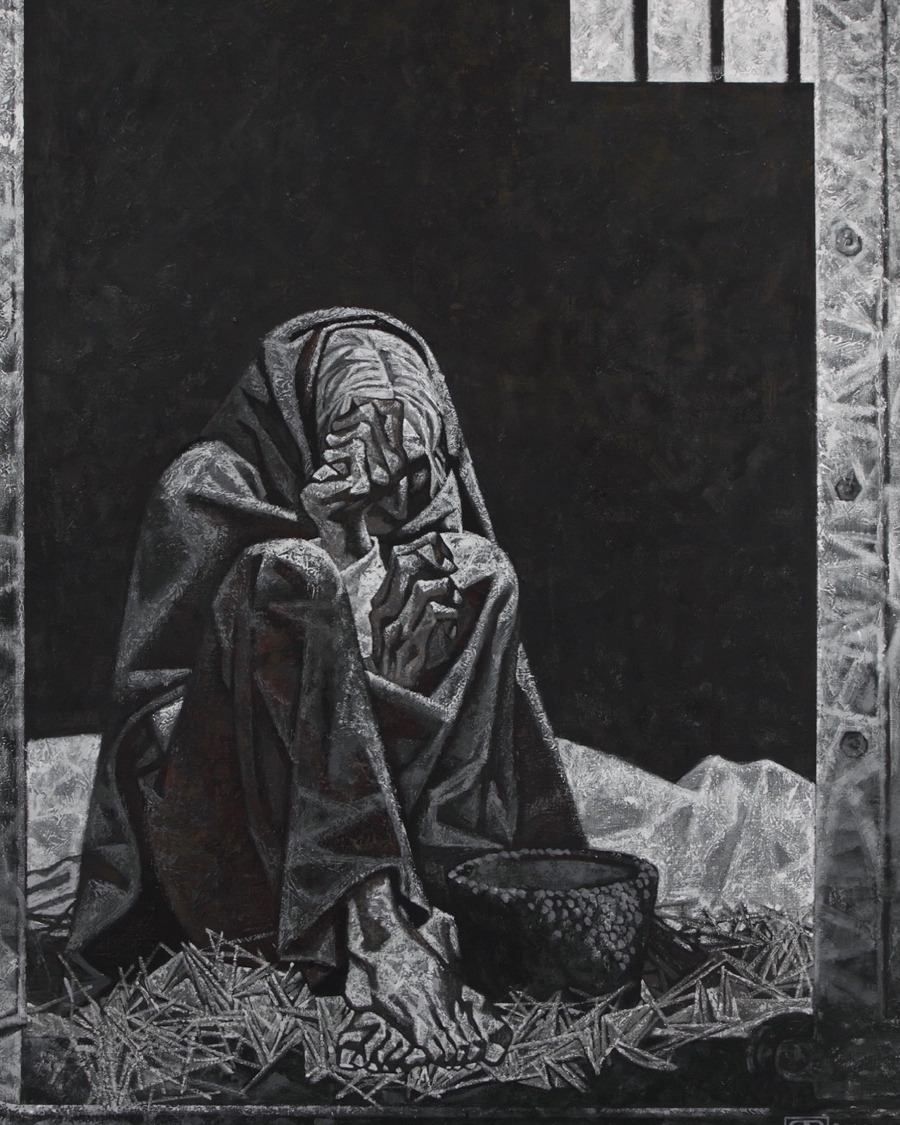

Eventually, we were left in a vast wasteland. Far in the distance, a small hut came into view. But we couldn’t move, we were paralyzed by cold and hunger. Arbi and Khutmat clung to me on either side, trying to stay warm. Kharon said nothing. When I looked at him again, I saw the colour had left his face. His eyes were closed.

The wind was sharp and biting, tearing through our thin clothing, battering us like it wanted to rip apart what little life remained in our small bodies.

In my young mind, everything blurred together: the cries of mothers, the wailing of children. I didn’t know if it was real or a terrible dream.

— Selima, there’s a hut ahead… we have to reach it, — Mommy said, her voice faint.

— Mommy, Kharon is blue… his eyes are closed.

— Give him to me.

Then our Mommy took Kharon in her arms and cried out with all her strength:

— Kharon, wake up! Wake up, my dear! We survived! We made it! You must open your eyes! I promised your father I would protect you even from myself! Please… wake up!

Her tears hadn’t even reached her cheeks before they froze into tiny crystals. We didn’t even have the strength to cry. We clung to our mother and stood there, motionless in the cold, unsure what to do.

It was the first time I had ever seen my mother in such boundless despair. Then Khutmat fainted. And at that moment, Mommy understood: if we didn’t find shelter soon, we would all perish. She gathered every last bit of strength, and somehow, we reached the hut. We stumbled through the door and collapsed onto the floor, completely spent.

It was freezing inside. But despite the cold, the children fell asleep at once. My mother and I sat in silence, exchanging a single look, then glancing at Kharon’s small, lifeless body lying beside us. The only warmth in that room came from the tears that ran down our frozen, tormented faces. Trying to soothe me, my mother whispered softly:

— Selima, close your eyes and imagine our home… The Caucasus. Its mighty mountains. The crystal rivers that tumble into cool, shimmering waterfalls. The endless green valleys and steep, unreachable cliffs. Our cozy home, where we’re all together. And Kharon… He’s no longer cold. He’s with the Almighty now. My little boy.

She kissed his icy cheek and embraced him tightly, as if trying to bring him back with her warmth. Then, gently, she began to sing our favourite lullaby:

Sleep, little one,

With a sweet dream,

Wake up, little one,

With a deep mind.

May a sweet dream visit.

Let sweetest dreams alight.

Upon my little chick tonight.

From childhood, learn the way

To follow morals day by day.

Learn to speak the right,

Shun injustice, hold it light.

Give your elders their due,

Bring comfort to them too.

Your moral compass will stay bright,

If you hold respect upright!

Live honoring them through.

Sleep, little one,

Sweet dreams to you.

THE CHECHEN LANGUAGE

(The lullaby can be listened to via the link)

Дижалахь, жиманиг,

Мерзачу набарца,

ГIатталахь, жиманиг,

КIоргечу хьекъалца.

Мерза наб кхетийла

Жимачу кIорнина.

Жимчохь дуьйна Iамалахь,

Оьзда гIиллакхаш леладан.

Quietly, she carried Kharon outside. She buried him in the snow, wrapped in a blanket. When she returned, she lay down beside us, drew us close, and whispered a prayer for Kharon and for all the others who had passed. And so ended our journey into the unknown. And so began an exile that felt like eternity.

I remember that terrible, frozen day with horror. And yet, despite everything, my mother remained steadfast. She never let her strength falter.

— The Almighty is everywhere, — she would tell us. — Wherever we are, remember this. He is always with us. And we accepted our fate without complaint.

Then spring came. The snow melted. And it felt as though nature itself was trying to warm our frozen souls offering healing with the first rays of sun. Slowly, people began to build clay homes. They started to settle into this foreign land.

At first, the locals looked at us with suspicion. They called us savages, cannibals, as we were complete strangers to them. But after some time, as we talked, we found common ground. They realized that we were just human beings, like other people.

It was a harsh time. We couldn’t find work. People kept dying from hunger, from hopelessness. Death walked closely beside us. Later, Mommy managed to find work as a milkmaid. In the summer, she, my brother, and I worked in the fields.

That’s what saved us from starvation.

We made clothes from flour sacks. Shoes from cowhide. Everything was hard. Everything was raw.

I remember how our Mommy cried at night quietly, so we wouldn’t hear or see. And in the morning, she rose like a woman made of steel.

That fragile Chechen woman went to work, determined to feed her children.

Time passed. Relentless. There was no news from the front. We didn’t know if our men were alive. Or dead.

Over time, we began to adjust to life far from home. But the longing never left us. We missed the mountains… the crystal-clear streams and waterfalls, the fresh mountain air. We missed the Caucasus with all our hearts. We clung to hope. We kept dreaming that one day, we would return to our homeland.

Hundreds of times, we imagined what that long-awaited day would be like. And one day we did return. But not all of us.

Many were left behind in distant cemeteries. Forever. My father died on the front lines. My mother’s only brother disappeared without a trace. People clung to hope. They truly believed it had all been a mistake, and that soon everyone would be allowed to return. But that cruel mistake was not corrected until thirteen long years of endless waiting had passed.

«At 2 a.m. on February 23, 1944, the most infamous operation of ethnic deportation began: the forced relocation of the residents of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR — an autonomous republic formed just ten years earlier, following the merger of the Chechen and Ingush autonomous regions.

There had been deportations of the so-called «punished peoples» before — Germans and Finns, Kalmyks and Karachays. And there were others after — Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians living in Crimea, and Meskhetian Turks from Georgia. But Operation Lentil (Chechevitsa) — the eviction of nearly half a million Vainakhs, Chechens and Ingush — was the largest of them all.

Then, on January 9, 1957, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree: «On the Restoration of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR.»

The restrictions were lifted, and the Chechens, Ingush, and many other repressed peoples were allowed to return home.

Almost immediately, tens of thousands of Chechens and Ingush in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan left their jobs, sold their few belongings, and began the long journey back to their ancestral lands.

The day we were allowed to return became one of the most sacred and significant in our people’s history. Word spread like wildfire: «We’re going home.» And even the men wept with joy.

I remember the exact day we received the news. Our neighbour Zinaida came running and urged my mother to attend a meeting urgently. Mommy left us at home and went with her. We didn’t know why. And we were filled with worry.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.