Dedicated to A. P. Levich

About the Book

Annotations

1. Brief (for cover/catalog)

The Spark of Time is a book about how meaning shapes destiny. At the crossroads of science, philosophy, and personal experience, the author explores the nature of time, foresight, and altered states of consciousness.

2. Popular (for a broad readership)

The Spark of Time is a small luminous point in the history of our consciousness. This book tells how meaning and images become events, how altered states of consciousness (ASCs) open doors to other dimensions of time, and why foresight may be not a miracle, but a practical capacity.

3. Scientific-popular (for those interested in the future of science and culture)

What will change if we understand time more deeply? The Spark of Time shows that knowledge of the nature of time can transform science, culture, and human existence itself. Precognition, ASCs, quantum hypotheses, and new scientific methods converge here in a project of the future, where humanity learns not only to measure time but also to interact with it.

4. Academic (for specialists)

The author offers an interdisciplinary analysis of the phenomena of time, foresight, and altered states of consciousness. In dialogue with philosophy (Plato, Bergson, Jung), cognitive science, and psychotherapy, he formulates the concept of the «conversion point» and the working hypothesis of the «temporal crystallization condensate» (TCC) — a special informational-neurophysiological phase where structures of meaning obtain a statistical connection with future events. Methods (autogenic training, mask therapy), verification protocols, and proposals for experiments are presented.

5. Methodological (on new scientific methods)

The Spark of Time also raises the question of new methods of inquiry. How do we study unique cases — foresight, dreams, the destinies of individuals and societies — if classical science demands repeatability? The author proposes the foundations of a «new science of time,» where preregistration, living registries, and cognitive protocols matter. The book opens a path toward a philosophy of science oriented toward the unique and the future.

6. Literary-philosophical (on the meaning of the book as a text)

This book is not only a study but also a confession of a seeker. The Spark of Time is a path between reason and imagination, where meaning becomes the breath of the world and time reveals itself as the mirror of the soul. At the crossing of science and myth, philosophy and personal experience, a new understanding is born: time is a companion, a guide to eternity.

7. Personal (from author to reader)

This book was born out of my encounters with time — in dreams, in dialogues with patients, in scientific debates, and in the silence of autogenic training. I wrote it both as a researcher and as a man for whom time is a living reality, full of pain and hope, loss and revelation. These pages contain my experience, my questions, and my sparks of hope. I invite you to enter the conversation: about the future, about meaning, about our human destiny.

Unlocking the Dimensions of Time: A Journey into Temporal Psychology and Consciousness Forecasting

Editorial Introduction by Sergey Kravchenko (assisted by AI)

In this groundbreaking work, psychologist and consciousness researcher Sergey Kravchenko invites readers to explore the intricate interplay between past, present, future, and the eternal. Drawing on decades of practice in altered states of consciousness (ASC) and temporal psychology, Kravchenko presents a methodical yet deeply intuitive approach to understanding how the human mind perceives and anticipates time.

This book is not just a study of psychic phenomena or theoretical frameworks — it is a practical guide to registering, analyzing, and interpreting precognitive signals, bridging science, philosophy, and lived experience. Through meticulously documented case studies, including rare and non-replicable events, readers will gain insight into the rigorous methodology that transforms seemingly elusive foresight into verifiable, meaningful knowledge.

For anyone intrigued by the frontiers of consciousness, the science of time, and the art of anticipation, this book offers a unique lens to understand how our minds navigate the continuum of existence — and how we can learn to engage with the future before it unfolds.

Introduction

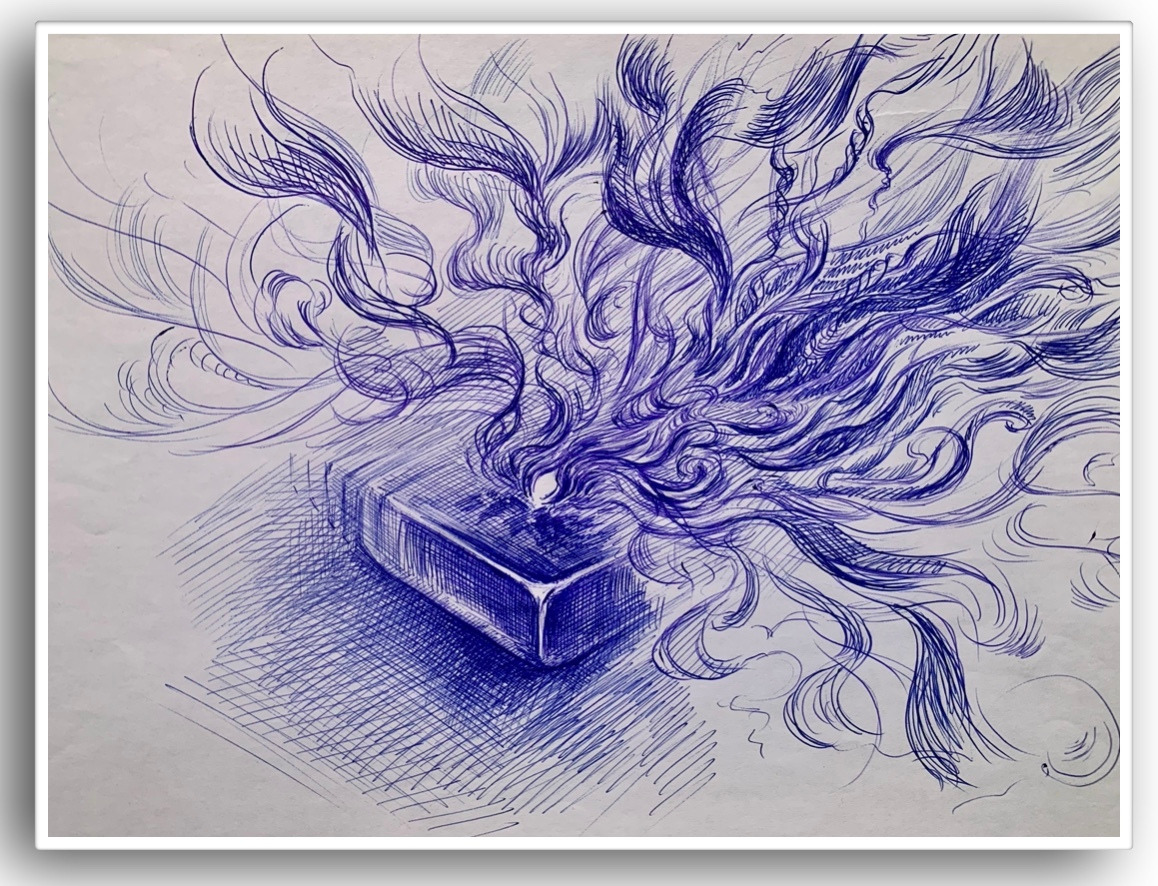

All my life, time has been for me not only a theoretical question — it has come as an experience. More than twenty years ago, in a half-dream, I received a vision that has since become the axis of my reflections and practices. I saw not a line of clocks and calendars, but a fold of space where two worlds coexisted: the material world — with things, events, bodies — and the world of images — ideal, Platonic, composed of meaning and archetypes. Between them glimmered a small spark, like the light of a candle. This was not merely a symbol: within it an exchange occurred — ideas were transmuted into material entities, and matter, as in a forge, generated images and concepts. This process was continuous, akin to metabolism in a living organism; every movement of meaning resonated in the world of events, and every event bore within itself the seed of an image.

Later, again in a half-dream, another simple yet important distinction opened to me: in our experience, there are two senses of time — the measurable (what clocks and instruments register) and the immeasurable (what we live as duration, meaning, kairos). They coexist within each of us and at times come into conflict: one gives us planning, agreement, and order; the other — depth, intuition, and the possibility of seeing the world not only as a sequence of events but as a fabric of meanings. On the border of these modes, special states emerge — thresholds where the sense of time alters its nature.

In my clinical practice, and in working with people who came to me for help, I encountered yet a third form — timelessness. This is the experience when the usual supports of past and future vanish; not Platonic eternity, not an ordered «forever,» but a state in which meanings blur and the personality temporarily loses its foothold. Patients described such experiences as «falling out» of time, and for some it became traumatic — they lost orientation, shielded themselves with rituals, or enclosed themselves within dogmas. Understanding timelessness, its nature, and safe ways of leading people out of it became an important part of my therapy: from this arose methods of support and integration — including mask therapy, which helps restore the boundaries of the «I» during intense ASC experiences.

My years of practice — autogenic training since the age of twenty, long psychotherapeutic work, seminars and clinical cases — went hand in hand with scientific and organizational efforts. I collaborated with the Institute for the Study of the Nature of Time under the direction of Alexander Petrovich Levich and was the initiator of the International «Center for Anticipation» (2008–2018). There we built databases, discussed methods for testing foresight, and sought a balance between empiricism and cautious interpretation. All of this — diaries, ASC records, collective discussions — became material for this book.

In the present work I attempt to summarize many years of experience and knowledge and to move further: together with the tools of artificial intelligence I formulate a working hypothesis that I call the temporal crystallization condensate (TCC). TCC is both an image and an experimental idea: a local phase of ordering, when structures of meaning and neurophysiological coherence create conditions in which an image may acquire a connection with a probable future. I do not claim a final formula; I propose a hypothesis, describe a methodology for testing it — recording protocols, verification criteria, neurophysiological metrics — and invite colleagues in science and practice to collaborate.

In this book I weave together several layers: personal experience and the observations of a therapist; philosophical reflections on time (from Plato to contemporary thinkers); scientific data on the perception of time, brain rhythms, and altered states of consciousness; and methodology — how to record, how to test, how to work ethically with information about the future. I address both the general reader and the specialist: the one who wishes to understand what is happening within him in a state of inspiration or anxiety, and the one who studies time in the laboratory, writes papers in cognitive science, or develops technologies related to quantum systems and AI.

Let me briefly outline the key concepts and themes that will frequently appear in this book:

— Measurable time — metric, instrumentally defined;

— Immeasurable time — duration, meaning, subjective flow;

— Conversion point — threshold/platform where meaning becomes a potential signal of an event;

— Temporal crystallization condensate (TCC) — a working hypothesis of a local phase of meaning-ordering and neurophysiological coordination;

— Altered states of consciousness (ASCs) — practices and states granting access to the immeasurable;

— Timelessness — a state of falling out of habitual temporal supports;

— Mask therapy and integrative practices — clinical methods for safe entry into and exit from ASCs.

Where and how is this applicable? On the personal level — in therapeutic work: understanding temporal modes helps restore grounding, distinguish anxiety from insight, and carefully integrate experience. In social and collective life — in decision-making, strategic planning, crisis management: if foresight becomes a disciplined instrument, it may strengthen the resilience of communities; at the same time, it requires ethics and regulation. In science and philosophy — TCC offers a bridge between the phenomenology of meaning and formal models of time; in technology — ideas of temporal phases and informational coherence may provide new approaches to data analysis and interaction with AI.

I write directly and honestly: in this field there are many delicate boundaries. I pose questions, but I also preserve the sense of experience — that which cannot be reduced to graphs and formulas, but which manifests in lived reality. My request to you, reader: approach this material with curiosity and with criticism at once. Record your dreams and note your moments, apply the proposed protocols with care, and help us together to turn the spark of time into a clear instrument of understanding — not for dominion over the future, but for a more truthful and careful relationship with it.

S. A. Kravchenko

August 2025

Part I. Time in Human Experience

Chapter 1. Time in Myths, Religions, and Philosophy — from Plato to Heidegger

«Time is the moving image of eternity.»

— Plato

The history of humanity is, to a great extent, the history of our attempts to understand time. With the first calendars and sacrifices, people sought not merely to mark the rhythms of nature, but to rationalize and gain power over what slips away: the waking and falling asleep of the day, the change of seasons, that which leads all living things to their end. From these attempts were born myths, rituals, and philosophical teachings — different answers to the same question: What is time, and how should we live with it?

Myths and Religions: Personifications and Rhythms

In mythical imagination, time often takes a face. Among the ancient Greeks, two striking figures stand out. On one side is Chronos, the cruel ruler who devours his children, symbolizing relentless, destructive flow. On the other side is Kairos, the «moment,» the opportune chance, qualitative time of action: not what clocks measure, but what the soul feels. This pair — chronos and kairos — remains one of the key tools for distinguishing two modes of time, to which we constantly return in both practice and theory.

In Egyptian myths, time has a cyclical character: each morning the god Ra rises, overcoming darkness, and this ritual is an act of restoring cosmic order. In the Indian tradition, Kala (time) simultaneously destroys and creates; in the Bhagavad Gita, time appears as a force of destruction and transformation — devouring forms so that the new may be born. In my own observations, it is precisely this duality — destruction and creation — that often emerges in altered states of consciousness: the «past» dissolves, making space for the «new.»

For the monotheistic traditions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), time is given a linear meaning: the world has a beginning and a direction, history moves toward an end. In Christianity, this is expressed in the ideas of salvific history and resurrection; Augustine formulated the paradox of human experience of time with striking clarity: «What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain to one who asks, I know not.» His thought emphasizes that time is both an immediate datum of experience and a problem of language.

Buddhism, by contrast, emphasizes impermanence (anitya) and points to the illusory fixation of the «self» in time: liberation is connected to the experience of the present, with stepping outside the circle of samsara. In mystical traditions (both Eastern and Western), the image of the «timeless present» often appears — a state in which time as succession disappears, leaving only pure presence.

The Philosophical Tradition: From the Image of Eternity to Existence

Philosophers deepened and complicated these notions. Plato, in the Timaeus, called time the «moving image of eternity»: the ideal exists beyond time, while the sensible world is its reflection, subject to change. Aristotle gave the well-known definition: «time is the number of motion with respect to before and after,» embedding in the concept a relation to change and measure.

In the modern era, a debate arose about the status of time: Newton conceived it as an absolute background, a uniformly flowing «substance,» independent of the world; Leibniz regarded time as nothing more than relations among events, derivative of the interrelations of things. This dialogue — whether time has its own «reality» or arises from relations — remains relevant today.

Kant proposed a radical idea: time (like space) is a form of our sensibility, an a priori structure in which we construct experience. This was a shift: time is no longer merely a property of the world, but a condition of our cognition. In the 20th century, Husserl deepened the phenomenology of inner time, analyzing the stream of experience — the «stretching» of consciousness that cannot be reduced to mechanical divisions. Henri Bergson opposed «duration» (la durée) to mechanical time: for him, the present is not a sum of instants but a fused flow of experience.

Martin Heidegger, in Being and Time, shifted attention to the existential dimension: time is not the backdrop of existence but the very mode of human being. He showed that human Dasein is always «oriented toward the future,» yet permeated by being-toward-death; the notion of Sein-zum-Tode (being-toward-death) places time at the center of existence. For Heidegger, temporality is the horizon through which the meaning of being is disclosed.

Contemporary Questions: Thermodynamics, Arrows, and Relativity

Classical physics conceived of time as a parameter measured uniformly; the 20th century overturned this conception. Einstein’s relativity bound space and time into a single fabric — space-time — where local clocks tick differently depending on velocity and gravity. Here, there is no single «external» flow: time is local. Another crucial context is thermodynamics: the notion of the «arrow of time» (the direction from order toward entropy) explains why we remember the past but not the future. Boltzmann and his followers linked our historical sense of time’s direction to probability and chaos.

These scientific discoveries impart two key lessons to contemporary thought: (1) time can be local and relative, and (2) its direction is connected to information and thermodynamics. For us, this is crucial because it opens the possibility of a more complex model — where time not only «runs» but also «takes form» in particular conditions.

Conclusion and Transition to Practice

Through myths, religions, and philosophy runs a constant theme: time is not a passive backdrop but an active co-author of human life. From these traditions, we inherit a set of key images and concepts that I use throughout this book: chronos and kairos, duration and measure, linearity and cyclicity, «timeless presence» and existential temporality.

But I want to go further — not limit myself to the history of ideas. My clinical and research experience (altered states of consciousness, mask therapy, the Center for Anticipation, collaboration with the Levich Institute) shows that in human experience, time reveals other qualities — thresholds, points of conversion, moments when meaning and event enter into dialogue. In the following chapters, we will move from the history of ideas to a description of those phenomena of time that can be observed and tested in practice, and to a working hypothesis — the condensate of temporal crystallization (CTC) — as an attempt to connect the phenomenology of meaning with neurophysiology and theoretical physics.

Chapter 2. The Psychology of Time: Subjective and Objective Dimensions

«The specious present is the short duration we are immediately and incessantly sensible of.»

— William James

Time is one of the most reliable and at the same time the most elusive categories of human experience. It seems so self-evident that we rarely stop to describe it; but once we try, the simple picture dissolves into layers of theory, phenomenology, and personal experience. I always find it useful to keep two axes at hand — the objective (that which clocks and equations measure) and the subjective (that which a person experiences). Yet their separation is conditional; and the attempt to bring them together yields more than a mere sum.

Objective Time — Not the Simplest of Realities

Traditional classical physics treated time as a uniform background scale, identical for everyone — this was the Newtonian image. The 20th century introduced corrections: Einstein’s theory of relativity showed that the «sameness» of time is an illusion; the ticking of clocks depends on speed and gravity — time becomes local and relative. For practice, this carries a simple implication: there is no single universal «arrow,» but local rhythms and connections.

Beyond that lies quantum physics and cosmology — domains where the familiar «before and after» sometimes blur: the order of micro-events may not be strictly determined, and interpretations such as Everett’s «many-worlds» suggest the branching of realities. In theoretical physics, time may be multidimensional and part of a more complex structure than the one we are accustomed to. For us, as practitioners, this set of ideas matters not for its abstraction, but because it opens space for a model in which «time» can be locally reconfigured — what I later called the working hypothesis of the QTC (Quantum-Temporal Configuration).

(Behind this paragraph stands a serious body of scientific literature on relativity and modern hypotheses: Einstein on space-time and contemporary reviews on temporal structures.)

Subjective Time — The World of Experience

Subjective time is what we feel: the stretch of a minute in anxiety, the «flight» of an hour in the flow of creativity, the weight of memories that make the past heavy. This realm is closely tied to memory, attention, and emotion — but even more deeply, to states of consciousness. Altered states (meditation, hypnosis, autogenic training, sensory deprivation, psychedelic sessions) change not only the content of experience but also the very metric of time by which the brain organizes events. Research shows: experienced meditators regularly report a «slowing down» of time and an increase in the density of present experience. This is not just poetic description — empirical studies record stable changes in subjective time among practitioners of mindfulness. (Frontiers, PubMed)

Neuroscientific data provide us with working tools: there are brain networks associated with self-reflection and «background» activity — above all, the Default Mode Network (DMN). Immersion in a task or in a meditative state reduces DMN activity; in psychedelic states its organization is reconfigured. This correlates with the loss of ordinary self-reflection and with altered time perception. Such observations link the phenomenology of experience with concrete neurophysiological markers. (PNAS, annualreviews.org)

Psychedelics represent a separate case, now re-emerging into scientific discourse. Under the influence of psilocybin and similar substances, people often experience distortions in the familiar time scale: the sense of «stretching» or «dissolving» time, the loss of self-boundaries, the intensification of sensory connectivity. Neuroimaging shows that during such states the brain’s functional connectivity reorganizes, and its repertoire of dynamic states expands — providing physiological grounding for the experienced «blurring» of time. (PubMed, PMC)

Extreme Experiences: Near-Death States and the «Eternal Present»

Reports from people who have survived clinical death or deep near-death experiences often contain vivid temporal phenomena: «a whole life in an instant,» or the presence of countless images and events within one «now.» The large prospective AWARE study recorded a wide spectrum of cognitive experiences in cardiac arrest survivors; some reports pointed to the persistence or return of consciousness under conditions traditionally considered anatomically incompatible with awareness. These data do not offer an unequivocal interpretation of «timelessness,» but they do show that in extreme states subjective time can diverge radically from the linear model. (PubMed)

Ancestral Memory and Unconscious Layers of Experience

Our sense of the past is not limited to personal autobiography. Modern biological research points to inheritance mechanisms that shape descendants’ reactions: classical experiments on the transmission of specific fear responses across generations indicate epigenetic traces of experience. This does not prove «ancestral memory» in the mystical sense, but it provides a scientific context for understanding why in collective and archetypal images the past can feel more alive than mere recollection. For the psychologist, this means that representations of the past may emerge from deep intergenerational layers of the psyche, not only from individual memory. (PubMed, PMC)

Attention, Intentionality, and «Where the Present Resides»

Traditionally, psychologists said: «attention keeps us in the present.» I prefer a more precise formulation: the present is held by the intentional orientation of consciousness — the capacity to point «toward» a significant locus of the world. This notion, borrowed from phenomenology, helps explain why certain temporal objects (for example, the memory of a beloved person or the anticipation of danger) become centers around which the whole experience is organized. This intentionality also underlies the effectiveness of therapeutic methods: changing intentionality (reorienting attention, symbolic processing) alters the quality of the time in which a person lives.

Integration: The Boundary Between Dimensions Blurs

Bringing scientific and phenomenological observations together makes it clear: the boundary between «objective» and «subjective» time is conditional. Physics shows the locality and relativity of time; neuroscience shows that brain states reshape our metric of experience; psychology and epigenetics point to deep influential layers of memory and meaning. Taken together, they suggest that time is not a single background, but a multilayered fabric — something that can be studied and, under certain conditions, reshaped.

Transition to the Next Chapter — Experiences Beyond Time

If physics and cognitive science provide frameworks and tools, then a natural question arises: can this be experienced firsthand — purposefully or spontaneously? I do not limit myself to theory: in the next chapter I will describe my own experience of stepping beyond the familiar temporal scale, the methods of entering altered states of consciousness (autogenic training and other practices), clinical observations, and the checks that make foresight and altered states the subject of disciplined research.

Key Sources and References (for specialists and further reading):

— Wittmann, M. Subjective expansion of extended time-spans in experienced meditators (Frontiers in Psychology, 2014). (Frontiers, PubMed)

— Raichle, M. E. et al. A default mode of brain function (PNAS, 2001) and review works on the DMN. (PNAS, annualreviews.org)

— Studies on psilocybin and brain dynamics (e.g., increased repertoire of brain dynamical states under psilocybin; Carhart-Harris et al., various studies). (PubMed, PMC)

— AWARE studies on awareness during resuscitation (Parnia et al.). (PubMed)

— Dias, B. & Ressler, K. J. Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations (implications for transgenerational epigenetic memory). (PubMed, PMC)

Chapter 3. Altered States of Consciousness and Transcending Time: The Author’s Experience

«If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.»

— William Blake

Altered states of consciousness (ASC) for me are not a poetic metaphor, but a working laboratory. Within them, the habitual flow of time disintegrates and reorganizes anew; within them, the boundaries of the «I» dissolve, and past, present, and future may become interwoven in a single experience. I came to this gradually — through practice, observation, and thousands of hours of recording — and I wish to describe here not only the sensations themselves but also how they may be aligned with contemporary scientific perspectives.

My acquaintance with the subject began at the age of twenty through autogenic training. This method became my key to inner states: regular practice led to stable shifts in perception and to the possibility of entering what I later came to call the «conversion point.» Once, in a dream, numbers appeared to me — the sequence almost coincided with the winning combination of the «Sportloto» lottery. I awoke, hesitating whether to write them down — and this hesitation clouded my memory. Years later, a similar episode recurred with the «Stoloto» lottery: the image was there, the win was real, yet in both cases an error crept in — and I drew from this an important lesson: the mere fact of an experience does not automatically guarantee accuracy. Recording, protocols, and verification — these are what distinguish a random image from a reliable signal.

The Arctic became my «polar» laboratory of time. During the long nights, in the silence of snow and wind, I read and wrote extensively — Jung and Grof, books on the collective unconscious and on trance experiences. Stanislav Grof provided me with a map of states and practices that enabled me to comprehend experiences beyond the ordinary cognitive framework. Castaneda at the time seemed to me more of a literary reconstruction, but in the works of Grof and Jung I found both clinical and conceptual foundations for what I was observing myself. (Holotropic Bohemia, SCIRP)

The practices by which I entered ASC varied: autogenic training, prolonged sensory deprivation, periods of deliberate overexertion during my polar expeditions, meditations, and intentional role-playing techniques. Each path revealed the same: the temporal structure of experience reorganizes itself — the rhythms of consciousness alter the relation between «before» and «after,» and in place of linear flow arises a dense fabric of «present,» within which past and future coexist simultaneously in different qualities.

Modern neuroscience does not contradict these observations — it complements them. Reliable evidence exists that the brain’s «background» networks (especially the Default Mode Network) alter their activity in states of rest, meditation, and under the influence of psychedelics; these reorganizations correlate with changes in self-reflection and the perception of time. Raichle and colleagues described the DMN as a mode present during rest and associated with autopoietic processes of consciousness; when engaged in tasks or in other states, its configuration changes. (PNAS) Moreover, studies of meditative practice show that experienced practitioners regularly perceive a «stretching» of time and a greater density of the present. (PMC) Similar reorganizations are observed in research on the effects of psychedelics: they alter functional connectivity and dynamic complexity, accompanied by distinct transformations in temporal perception. (PNAS, PMC)

I do not elevate ASC to a sanctuary of truth: they are an instrument, and like any instrument, they require knowledge, technique, and safeguards. In clinical practice, I have repeatedly witnessed the reverse side: for some patients, spontaneous «falling out» into timelessness became a trauma. People lost their anchors, felt the shadow of death, saw catastrophic images — experiences that disrupted their life structures and led to depression or psychosis. These observations brought me to two important conclusions: (1) accompaniment and integration are indispensable; (2) safety techniques are necessary, providing the personality with support upon return to ordinary time.

Mask therapy became precisely such a protective «arsenal» for me. Under the guidance of its founder, G. M. Nazloyan, I studied and practiced mask-therapeutic work for many years — until his passing — and applied it as a stabilizing element in work with clients who had undergone deep ASC. In my experience, mask therapy is not merely a creative play but a method enabling symbolic consolidation of what has been lived through, restoring the boundaries of the «I» and giving the image a safe form of integration. (I studied the method under Nazloyan’s supervision and applied it in clinical practice.)

Moving to Moscow and meeting Alexander Petrovich Levich, initiator of the Institute for the Study of the Nature of Time, gave my work both scientific and organizational scope. At the Institute, and later in the International Center for Anticipation that we established, we undertook systematization: collecting diaries, formalizing protocols of entry into and exit from ASC, testing verification criteria of foreseeing, and applying expert systems and AI to analyze a large corpus of signals. Practice showed that the reliability of foreknowledge increases with the discipline of protocol: temporal markers, independent verification, expert consensus, and statistical checks reduce the share of erroneous interpretations.

Theoretically, I advanced a hypothesis I called the condensate of temporal crystallization (CTC): under certain conditions, consciousness and the semantic structure of experience attain such coherence that at the «conversion point» the image acquires an increased statistical correlation with a probable future. This is not alchemy or magic — it is a working model, testable through neurophysiology, semantic analysis, and event-base verification. CTC is an attempt to link the phenomenology of ASC with real markers (theta/alpha rhythms, changes in DMN organization, indicators of complexity and synchrony) and with methodology: protocols, blind testing, and AI support.

It is important to emphasize: I do not claim that ASC provide «truth» automatically. They provide the possibility of noticing signals and meanings that remain invisible outside of practice. Our task is to cultivate a reliable methodology — as an archaeologist cleans and documents a find before presenting it to the world.

Finally — a philosophical note. Those who study consciousness and time often dispute the limits of scientific explanation. I propose a practical compromise: to preserve skepticism and method, yet not close the door to phenomenology. Altered states provide access to experiences that cannot be reduced in advance; science supplies the tools for their documentation and analysis; psychotherapy offers ways of integrating and protecting the personality. In this triad — empiricism, theory, and clinical ethics — I see a path that can be pursued both cautiously and boldly.

Key scientific references underlying this chapter:

— Stanislav Grof — works on holotropic breathwork and the cartography of non-ordinary states of consciousness. (Holotropic Bohemia)

— C. G. Jung — the concept of synchronicity as meaningful correlation without explicit causal connection. (SCIRP)

— Raichle M. E. et al. — «A default mode of brain function» (description of the DMN). (PNAS)

— Wittmann M. — studies on the subjective expansion of time among meditative practitioners. (PMC)

— Contemporary reviews on psychedelics and the reorganization of functional connectivity (Carhart-Harris et al.). (PNAS, PMC)

Part II. Time in Science

Chapter 4. Classical Physics and the «Arrow of Time»

«The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.»

— Rudolf Clausius

When I speak with people about time, the first resistance usually appears at the level of imagery: many still imagine time as a straight river, slowly carrying us from the past to the future. This Newtonian image — of «absolute, true, and mathematical time,» as Newton wrote — is convenient and simple. It gives us a scale for calculations, clocks, and calendars by which social life is structured. Yet reality turned out to be trickier, and already in the 19th–20th centuries we had to accept: time is not necessarily that simple.

The Arrow of Time — from Experience to Law

The idea of the «arrow of time» translates a scientific problem into an image. Arthur Eddington, as early as the beginning of the 20th century, proposed this metaphor to emphasize a simple thought: the world appears directed — we remember the past and anticipate the future; a glass that falls on the floor does not reassemble; cooks do not return a thick stew back into the pot. Why is that? The answer of classical physics came in the formula of thermodynamics: the second law, the growth of entropy — and, with it, Ludwig Boltzmann’s statistical picture, explaining irreversibility as a matter of probabilities.

It is important to pause here: the microscopic equations of mechanics are reversible — they can formally be run backward, and they remain valid. Yet the macroscopic picture — the one visible to humans in daily life — is consistently non-reversible. Here physics meets philosophy: the arrow of time can be explained statistically (an ordered set of microstates is rare; chaos is common), but the question remains why, under our specific conditions, the initial state so often turns out to be more ordered than what follows.

This statistical picture was challenged by Loschmidt and Poincaré: if the equations are reversible, why do we not observe reverse processes? Why do we not speak of return? The answer involves ideas about the initial conditions of the Universe and about scales of probability — a question that is not only mathematical, but cosmological. One way or another, in human experience the «arrow» is felt as fact — and its connection with entropy gives us the first, physical foundation for irreversibility.

Human Beings, Memory, and Direction — Where the «Arrow» Meets Life

For psychology and for my clinical observations, it is important that the physical arrow is closely linked to information: the growth of entropy resembles the loss of information about an initial order. We remember the past because structures are inscribed in it — traces of ordered states; the future, by contrast, is rich in possibilities but poor in determinacy. In this sense, memory acts as a local «retransmitter» of order: it preserves the sequence of events and thereby sustains the subjective directedness of time.

Yet human experience gives us other voices. In deep grief, the past pulls us back; in ecstatic creativity, the present expands into infinity — and it seems the temporal arrow is temporarily blunted. These phenomena do not contradict physics; they indicate that time has both objective and subjective «faces» — and where they meet arises a field for psychological and philosophical exploration.

Jung and Archetypal Time: Circles of Meaning

Here I take a step from physics toward psychology, but not toward unscientific mystification: Carl Gustav Jung introduces the concept of archetypes — fundamental universal structures of meaning, «primordial images,» that manifest in myths, dreams, and rituals. For Jung, time is not simply linear: archetypes operate «outside of time» and simultaneously influence past, present, and future, creating repeating motifs and cycles in the lives of individuals and collectives.

The Jungian perspective gives us another «arrow»: not the arrow of entropy, but the arrow of meaning. Where physics speaks of direction in terms of order changing, psychology shows that human history is full of «returns» — recurrent symbols, recurring dramas, not reducible to the law of probability. These repetitions are manifestations of the collective unconscious, and in therapy they often appear as «repeated plots» that must be recognized and worked through.

In my work with patients, archetypal time manifests vividly: symbolic repetitions, uncontrolled returns of old plots, «as-if» sensations when the past resurfaces and animates the present. This does not contradict physics — it is a different level of describing reality, and both levels are important.

Bringing Together the Facets: Entropy, Information, and Meaning

If we try to connect the Newtonian–thermodynamic picture with the Jungian one, we discover an intriguing possibility. Entropy is a measure of uncertainty; meaning is a local reduction of uncertainty, an act of ordering information. When collective archetypes activate, they condense meaning, create stable forms of behavior and perception. In conditions where meaning is locally strong, subjective time takes on a different density: memory becomes richer, anticipation becomes significant. It is precisely at this «border» — where statistics meet semantics — that I later place the concept of the conversion point and the working hypothesis of the TCC (Temporal Crystallization Condensate).

The Practical and Ethical Meaning of the «Arrow»

Understanding the arrow of time is important not only for physicists and philosophers — it shapes practice: therapeutic approaches, organizational decisions, risk management. If time at the macro level tends toward greater uncertainty (entropy), then individuals and communities need ways to locally sustain order — externally (structure, rules) and internally (symbols, rituals, mask therapy). In my experience, restoring personal boundaries and integrating lived altered states of consciousness proceeds through work with symbols and meaning — thus a person acquires tools for navigating a world where the arrow of time remains real, but its effects can be softened and guided.

Conclusion and Transition

The classical picture of the «arrow of time» gives us a foundation — thermodynamic and statistical — for understanding irreversibility. The Jungian perspective expands this picture by introducing the dimension of meaning and archetypes, which create cycles and repetitions in human life. Together they suggest: time is multilayered, and to grasp it, we must learn to shift between levels of description.

In the next chapter, we will turn to the revolution of the 20th century: to Einstein and the idea of space-time, where the «locality» and «relativity» of time take concrete mathematical form. For our theme, this is an important step: it shows how physics pushes the boundaries of the possible, while we — practitioners and philosophers — can take up the tools and listen to the new questions posed by the very fabric of reality.

Chapter 5. Einstein, Relativity, and Space-Time

«The distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.»

— Albert Einstein

The beginning of the 20th century changed my understanding of what «time» is — as radically as fire changes the face of metal. Albert Einstein showed that time can no longer be regarded as a single, universal background. Together with space, it forms a unified four-dimensional fabric — space-time — and the properties of this fabric depend on motion and mass. This is not a poetic metaphor but mathematics with real consequences: clocks standing side by side can measure different «times.»

I value two of Einstein’s aphoristic formulations. The first — often quoted in its classical translation:

«Time is what clocks measure.»

A simple phrase, but to my mind, extremely important: it reminds us that «time» in the physical sense is defined by the behavior of concrete systems (clocks). The second, more reflective thought — about the nature of space and time as forms of our thinking — forces us to recall that many notions we once believed absolute may turn out to be conditional in another context. Finally, his famous remark on past, present, and future — «for us physicists who believe, the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubborn illusion» — provokes the philosophical questions we will not avoid here.

What Does «Relativity» Mean in Practice

In Einstein’s special theory of relativity, the central idea is: the laws of nature are the same in all inertial systems, and the speed of light is constant. From this follows the destruction of absolute simultaneity: two events that are simultaneous for one observer may be non-simultaneous for another moving relative to the first. The impression of «one time for all» disappears: time becomes local, «proper» for each worldline.

In the general theory of relativity, space-time becomes dynamic: mass and energy curve the fabric, and this curvature affects the paths along which objects and light travel, and therefore the flow of local clocks. In practice this is no abstraction: experiments with precise atomic clocks confirmed the slowing of time both at high speeds and near massive bodies; the global GPS system works only because engineers account for corrections from both special and general relativity.

Another clear image is that of «proper time»: the «time» recorded by a specific clock (or observer) along its path in space-time. In the language of physics, each worldline has its own metric — and it may differ from that of another, even if they started out side by side.

Paradoxes and Intuitive Shocks

Particularly famous is the thought experiment — the «twin paradox» — in which one twin travels away at high speed and returns «younger» than the other. The resolution lies in the asymmetry of events (acceleration, change of inertial system) and in the fact that the proper model requires accounting not only for speed but also for the geometry of the trajectory in space-time. I often return to this example in conversations: it vividly demonstrates how different our intuitive, «human» moment of time is from physical proper time.

What Does This Mean for Our Understanding of Time as a Phenomenon?

For me as a researcher of consciousness and practitioner of altered states of consciousness (ASC), several important conclusions follow.

— Locality and multiplicity of «times.» Relativity introduces the idea that «time» is not a single property of the universe but a multitude of local parameters, depending on trajectories and conditions. This resonates with my distinction between measurable and unmeasurable time: physics shows that even the «measurable» is not singular.

— The right to a valid «order.» The notion of a single, unambiguous order of events dissolves — and this frees us methodologically: experiences in which the order of «past–present–future» shifts no longer automatically appear paradoxical. They fit into the broader framework of local temporal scales.

— The meeting point of science and phenomenology. If in physics «proper time» is the invariant metric along a trajectory, then for a subject there is a personal sense of time, also «invariant» for them. Here a dialogue is possible: biological rhythms, neurophysiological markers, and psychic states — all can be viewed as the subject’s «local clocks.» The TCC hypothesis, in which semantic and neurophysiological coherence create a local «crystallization» of time, can be read here as a proposal that under certain conditions consciousness may synchronize its «clocks» with informationally meaningful patterns of reality, thereby increasing correlation with event probabilities.

— Rethinking causality. Relativity does not abolish causality but complicates its form: the «dependence of times» forces us to take more care with concepts of one-way causality and event order. This resonates with the phenomena of synchronicity and foreknowledge — where the connection between meaning and event may not be linear.

Ethical and Practical Consequences

For psychotherapy practice and work with ASC, this has several consequences. First, the understanding of time’s locality strengthens my insistence on precise recording: temporal markers, context, the subject’s state — all are important, because the subject’s «clocks» and the «clocks» of external verification may run differently. Second, relativity suggests caution when interpreting «visions» and images: coincidence in content does not always mean coincidence on the same temporal scale. Finally, the theoretical recognition of multiple times provides an ethical basis for respecting subjective experiences; they cease to be «errors of perception» and become objects of study.

The End of One Fabric — The Beginning of the Next

Einstein’s revolution opened the door to a world where space and time ceased to be static stages for action. They became a weaving that reacts and responds to mass and energy. For me, this is not only a physical truth — it is an invitation to think of time as a dynamic resource, as a layer that can locally condense and crystallize, like a crystal forming a pattern in a flow.

From Einstein’s space-time begins the path to the ideas I explore further: quantum phenomena, time crystals, and — at the other end of the spectrum — the phenomena of consciousness, where time ceases to be only a dimension and becomes a medium of meaning.

In the next chapter, we will plunge into quantum physics and quantum entanglement: into a realm where the notion of time is again put to the test, and where surprisingly fruitful analogies arise with what I have observed in altered states of consciousness.

Конечно, я сохраню структуру с подзаголовками и маркированными пунктами. Вот перевод:

Chapter 6. Quantum Physics and Quantum Entanglement

«Entanglement is the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics.»

— Erwin Schrödinger

At the beginning of the 20th century, physics encountered something that, in human terms, looks almost mystical: the microworld turned out to be organized in a way completely different from what we are used to thinking, based on everyday experience. Quanta, superpositions, probability jumps — all this changed our language about reality. For the theme of time, the phenomenon of quantum entanglement is especially important: when two (or more) systems become part of a single whole, the measurement of one’s state instantly correlates with the state of the other — regardless of how far apart they are.

I want to emphasize two points that are often confused in popular accounts.

— First: entanglement is an experimentally confirmed fact (classic experiments — Aspect et al., 1982; numerous subsequent studies closed various «loopholes» in Bell inequality tests).

— Second: it is not about transmitting useful information faster than light — theory and experiments are consistent with the prohibition of superluminal signaling. Entangled correlations are real; they cannot be used to send a controllable message. This subtle but fundamental distinction must be kept in mind when we create metaphors and when we extend the idea into the domain of psychology.

What Experiments Have Shown and Why We Need to Know It

A series of experiments, in which Aspect (1982) played a key role, and much later «loophole-free» tests (Hensen et al., 2015 and others), demonstrated violations of Bell inequalities — meaning that quantum mechanics requires us to abandon either locality or a realist view of particles having properties prior to measurement.

Practically, this means: nature at its most fundamental level is organized differently from what we intuitively assume; connections are possible «beyond» local space-time in the sense that correlations cannot be explained by conventional local models.

These discoveries sparked a technological leap:

— Quantum cryptography (BB84 and later implementations) provides methods of secure key distribution.

— Quantum computing employs superposition and entanglement to solve problems inaccessible to classical machines.

— Quantum networks are already emerging — precursors of a future distributed quantum internet.

Theory and practice go hand in hand: we see that the principles of quantum mechanics work in engineering systems and can be harnessed for entirely new classes of technologies.

From Physics to Consciousness — Where Is Caution Needed?

For me, as a researcher of time and altered states of consciousness (ASC), it is natural to ask: if physics contains nonlocal correlations, could this serve as a metaphor (or even a model) for understanding deep connections between individual consciousnesses?

This question is tempting and often fueled in popular-science and parascientific discussions. Yet we must be precise: transferring concepts from one domain to another requires caution. Quantum entanglement is a strictly formal construct within the context of microscopic systems; any hypothesis about its role in the brain or in the interconnection of consciousness must withstand rigorous empirical testing and respect the constraints of physics (including the ban on faster-than-light communication).

Nevertheless, several research lines and hypotheses deserve attention and discussion — as fruitful, albeit controversial, directions.

Theories and Hypotheses (briefly, with «controversial» noted where necessary)

1. Orch-OR (Penrose & Hameroff).

The hypothesis suggests that microquantum processes in neuronal microtubules may contribute to the emergence of consciousness and that quantum coherence in such structures has functional significance (Penrose, 1989; Hameroff & Penrose, 2014). It is a beautiful and ambitious idea, but it remains controversial: critics point to problems with maintaining coherence in the «warm and noisy» environment of the brain (see Tegmark’s critique and others).

2. Global or collective consciousness.

Projects and ideas (ranging from parapsychological initiatives to efforts such as the Global Consciousness Project) claim that major collective events manifest in the statistics of random generators and that some form of «connection» between consciousnesses is possible. These projects produce intriguing data, but their interpretation remains highly contested and requires preregistered protocols and independent replications.

3. Quantum analogues in cognitive models.

In cognitive science, models have emerged that use the mathematics of quantum theory (without assuming quantum processes in the brain) to describe irrational probability shifts, superpositions of meanings, and contextuality effects in decision-making. Here, «quantum» is usually a mathematical metaphor, offering flexible tools for modeling cognitive phenomena.

Altered States of Consciousness and Quantum Metaphors

I often encounter the thesis: «ASCs show that consciousness transcends time; perhaps at this level some quantum logic operates.» I approach this with both respect and skepticism.

— On the one hand, ASCs indeed demonstrate phenomena of synchronicity, sudden insights, and experiences of «timelessness» — and the image of entanglement as the unity of scattered points seems fitting.

— On the other hand, to claim this as proof of the quantum nature of consciousness is premature. We need precise experiments: hypotheses, preregistration, statistical verification, and independent replications.

My preferred practical program looks like this:

— Use quantum physics as a source of methodological and mathematical ideas (new notions of correlation, nonlocality, contextuality).

— Construct tests at the levels of behavior, neurophysiology, and semantics that can be objectively verified.

For example:

— Study how moments of strong semantic coherence in a group (based on NLP analysis of verbal reports) correlate with changes in intersubject neural synchrony.

— Use randomized and blind protocols to test whether group alignment increases the likelihood of predictive coincidences above chance levels.

This is down-to-earth science, even if inspired by celestial metaphors.

Examples of Technological and Methodological Applications

1. Quantum cryptography and security.

Here the practical effect is already evident: the principles of quantum mechanics are used to generate and distribute keys whose interception is easily detected.

2. Quantum computing and data analysis.

The ability of quantum devices to efficiently explore vast state spaces promises tools for complex analysis of patterns in large databases of predictions and ASC diaries. AI + quantum algorithms may accelerate the detection of structures and patterns too subtle for humans to notice.

3. Hypothetical experiments on «intentional influence.»

Rigorously controlled, preregistered tests of whether human intention affects the statistics of quantum outcomes remain highly controversial, but, with proper methodology, could shed light on the limits of possibility (and usually yield null results when adequately controlled).

Neurophysiology: Where Quantum Remains a Metaphor, and Where It Offers Real Markers

So far, the most reliable connecting line is not a direct «quantum microchip of the brain → subjective experience,» but rather the fact that quantum ideas inspire new ways of thinking about information, correlation, and contextuality.

At the brain level, we have convincing markers of ASCs:

— rhythms (theta, alpha),

— reconfiguration of the DMN,

— changes in phase synchrony between regions.

These biophysical markers can be measured and analyzed, and hypotheses can be built on their basis. Precisely such multimodal protocols — EEG/fMRI + semantic analysis of prediction reports + statistical verification — provide a path from metaphor to scientific testing.

Ethical Notes and Methodological Rules

When we speak of subtle hypotheses (quantum consciousness, global mind networks), we must remember our responsibility. Such ideas easily become fodder for speculation, manipulation, and unscientific claims.

I insist on three rules:

— Preregistration of experiments and verification criteria.

— Blind verification and independent replication.

— Careful ethical evaluation of the impact on participants (especially in ASC studies).

Conclusion — Metaphor and Method

Quantum entanglement is not a ready-made instruction for understanding consciousness, but it is a powerful conceptual platform. It reminds us that the world at its foundation is connected in ways that defy our habitual intuitions of causality.

As a practitioner, I take from quantum physics not a dogma but methodological courage: to use nonlocal ideas as inspiration for new hypotheses — but to test them in grounded ways, through data, protocols, and replications.

Chapter 7. The Concept of the «Time Crystal» and Contemporary Research

«Time is nature’s way of keeping everything from happening at once.»

— John A. Wheeler

In recent decades, I have been increasingly drawn to those areas of physics and technology where time ceases to be a mere background and itself becomes a property of matter. The concept of the «time crystal» is one such idea — one that exerts a heavy yet subtle influence on my thinking, both as a researcher of altered states of consciousness (ASCs) and as a human being seeking bridges between meaning and event.

What is a «time crystal»? Briefly and to the point

The idea appeared in the work of Frank Wilczek in 2012: if an ordinary crystal breaks spatial symmetry by arranging atoms into a periodic lattice, then could we imagine a system that spontaneously breaks time symmetry and demonstrates periodicity within the flow of time itself? Such an object was named a «time crystal.» In principle, in its fundamental state the system can display ordered oscillations in time without consuming external energy in steady-state mode — behavior that in classical terms seemed impossible. Wilczek described it as a new state of matter «where time symmetry is broken just as spatial symmetry is broken in ordinary crystals.»

The idea soon found experimental confirmation: beginning in 2017, independent groups demonstrated discrete time crystals in controlled quantum systems (ion traps, superconducting qubits, and others). These experiments revealed the possibility of stable periodicity in time within open, driven quantum systems — a phenomenon now studied as a new phase of matter.

Why this matters to me as a psychologist and researcher of ASCs

At first glance, time crystals belong purely to quantum physics and engineering. Yet I am interested not only in the technology but also in the idea that time can locally condense into stable forms — «points,» «rhythms,» «structures» that hold meaning and provide support for events. In my terms, this is a direct metaphor and possible model for the conversion point and for the working hypothesis of the TCC (Temporal Crystal Condensate): local ordering of meanings and neurophysiological coordination, where semantics «crystallizes» and gains enhanced statistical linkage with probable futures.

If in a quantum system oscillation in time becomes stable and autonomous, then we may imagine a similar local autonomy in networks of consciousness: phases of heightened semantic coherence that «hold» and give form to events. This is not proof. It is a hypothesis, a methodological prompt: to study, to model, to experiment.

Scientific milestones and key contributions (briefly, by name)

— Theoretical initiative: Frank Wilczek (2012) proposed the idea of time crystals as a new type of symmetry breaking.

— Experimental realizations (2017 onward): independent groups demonstrated discrete time crystals in ion traps and superconducting systems (notably the observation of DTC in Nature 2017 and subsequent works), bringing the idea into the realm of experimentally accessible phenomena.

— Current directions: time crystals in spin chains, in superconductors, studies of robustness to noise and decoherence, applications in quantum simulations, and possible architectures for stable qubits.

Technological and practical perspectives

The practical side has significance both for technology and for consciousness:

— Quantum computers and stable qubits. Temporal structures may provide «self-sustaining» dynamics for storing quantum information, reducing decoherence problems. This opens a path toward more robust logical elements.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.